AS New South Wales reopens and Victoria edges towards its own reopening, recent modelling suggests these reopenings will trigger an escalation in cases, hospitalisations and deaths (here, here and here).

Vaccine targets have become part of the narrative; however, these are based on the average for the whole population. At current pace, groups at risk of poorer outcomes from COVID-19 – First First Nations Australians, people with disability and other disadvantaged populations — may be vaccinated at lower rates than the broader population as the country starts to reopen.

People with disability as an at risk population group

International experience shows people with disability are at increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 and more likely to become seriously ill or die if infected. In the UK, people with intellectual disability were eight times more likely to die of COVID-19 than the general population, and disabled people made up 58% of deaths.

Additionally, many people with disability are clinically vulnerable: they are more likely to smoke; have higher levels of obesity and chronic conditions such as diabetes and respiratory and cardiovascular disorders; and face barriers accessing high quality health care.

People with disability who require face-to-face support are more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 from support workers who may support other people with disability, with higher exposure for those living in settings with other people with disability, such as group homes and boarding houses.

Ethical and equitable vaccine allocation frameworks

Most countries faced the problem of limited vaccine supply. The World Health Organization has a roadmap for the allocation of COVID-19 vaccinations and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine released a framework for Equitable Allocation of vaccines. Both focus on maximising benefit in terms of social and economic wellbeing and health for the public. They also emphasise values and principles, including equal respect, where every individual is given meaningful opportunity to be vaccinated; equity, considering risks of groups who are vulnerable due to societal, geographic and biomedical factors; engagement with the public; and transparent, accountable and fair processes.

Prioritisation is part of an equity-focused vaccination, but it is insufficient. Schmidt and colleagues (2021) identify additional activities for equity-focused vaccination strategies, namely: greater share of vaccine appointments to priority groups, tailored outreach and communication, locating vaccination sites to ensure accessibility, and monitoring uptake of vaccination, including aspirations to reaching higher vaccination rates among disadvantaged, at-risk groups.

How does Australia’s vaccine strategy stack up for people with disability?

Prioritisation of people with disability

Consistent with principles of equal respect and equity, Australian people with disability were prioritised for vaccination. Those living in residential settings (group homes) were in Phase 1A – the highest priority. People with disability with chronic conditions and those with severe mental illness and intellectual disability were included in Phase 1B. Vaccination for Phase 1A was to commence in February 2021 and be complete by April 2021 and Phase 1B to commence in March 2021. Later, all participants in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) over 12 years of age were prioritised for vaccines.

More vaccine appointments

In February and March 2021, the vaccine rollout was limited to priority groups, meaning vaccine appointments should have been available. However, because of the failures in outreach, communication, and accessibility of vaccination sites, described below, this did not occur.

People with disability report the inaccessibility of the online vaccine booking system, difficulties getting through on the phone line for bookings, the eligibility tracker not being up to date preventing them from making bookings or not being recognised as being in the priority group, and getting conflicting advice from medical practitioners and COVID-19 helplines about their eligibility. As states and territories began to offer vaccines to people in later phases (eg, people aged 50–59 years, then 40–49 etc) people with disabilities found themselves jostling for vaccine appointments with people who had not been prioritised.

Tailored outreach and communication

The Commonwealth government did not do any targeted communication about vaccines before mid-2021. Even then, communications were largely on government websites with mixed availability of Easy Read material for people with low literacy, and Auslan videos. The first webinar on vaccines for people with disability, their families, and carers, was held by the Commonwealth government on 15 August 2021, and a webinar for people with intellectual disability and families was held on 1 September 2021 in partnership with Inclusion Australia – the peak advocacy body for intellectual disability.

In the absence of government leadership, many organisations have developed their own materials, but the lack of resources has them and other stakeholders doing more. The Victorian Government enhanced the role of their Disability Liaison Officers across health regions to support people with disability and supporters to find vaccine appointments in appropriate settings.

Planned location of vaccination sites to ensure accessibility

People with disability living in residential settings were promised a home visit for vaccination. Scheduled to begin in February 2021, by 17 May, only 999 residents (4%) had received at least one dose. In-reach COVID-19 vaccination clinics did not really start until mid-June.

Like the general population, people with disability were eligible to receive vaccination through GPs and vaccination clinics. However, some sites are not physically accessible and large vaccination hubs are not appropriate for some people with disability for whom crowded, noisy spaces may be overwhelming. Others have extreme fear of needles so sedation may be required, but access has been limited.

Initiatives such as the low sensory load clinics in the Australian Capital Territory and Sydney and in-reach vaccination to private homes have provided alternatives for some people with disability who might find it impossible to be vaccinated in other settings. But these initiatives have been patchy and not consistently implemented across States and Territories.

Monitoring vaccine uptake

The NDIS participant database and the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission’s screened worker database have been linked to the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) to monitor vaccination rates among NDIS participants living in disability residential settings and in the community as well as support worker vaccination rates.

While this information is critical, it misses many people with disability and an unknown number of care workers. NDIS participants must be less than 65 years at the age of entry, have a severe and permanent disability, and not be in another scheme that provides support (eg, accident compensation schemes). The NDIS includes nearly 470 000 participants, approximately 10% of the Australian population with disability. The NDIS screened worker database includes workers employed by providers registered with the Quality and Safeguarding Commission and linked to the AIR (approximately 170 000 workers). However, participants who manage their own funding can use unregistered providers, so the exact size of this workforce is unknown.

Until 5 September 2021, the government did not report any vaccination figures for disabled people or workers except in press releases, media reports and Senate Committees. Since then, the rates for NDIS participants living in residential settings and registered disability support workers are reported several times per week on their vaccine tracker dashboard. On 12 October the first dose vaccination national rates were 81.2% for NDIS participants in residential settings (n = 22 053) and 79.1% in disability support workers (DSWs) (n = 167 086) and second dose rates were 73.5% among NDIS participants in residential settings and 67.4% in DSWs. This compares to 83.2% and 64.4%, respectively, for the general population.

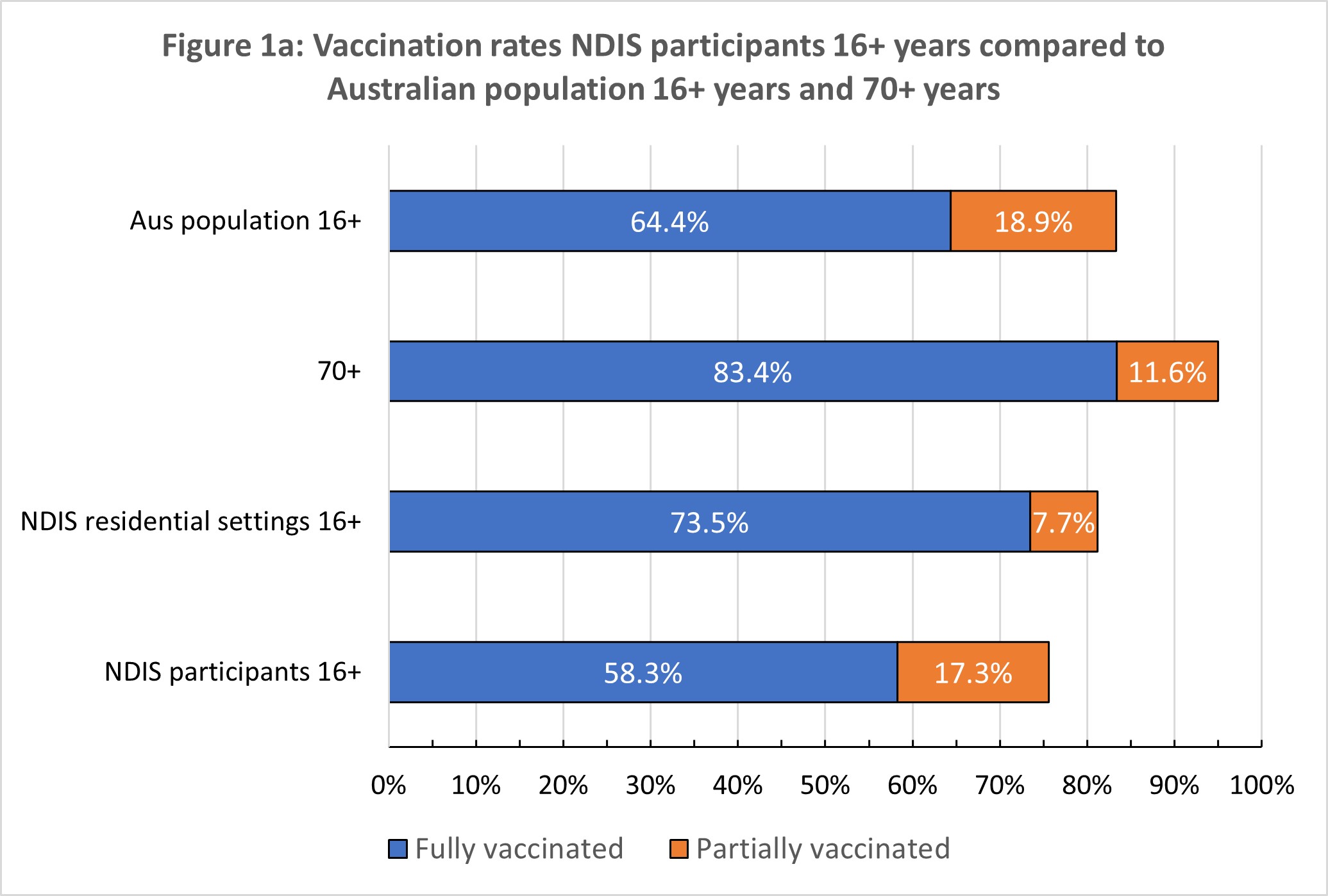

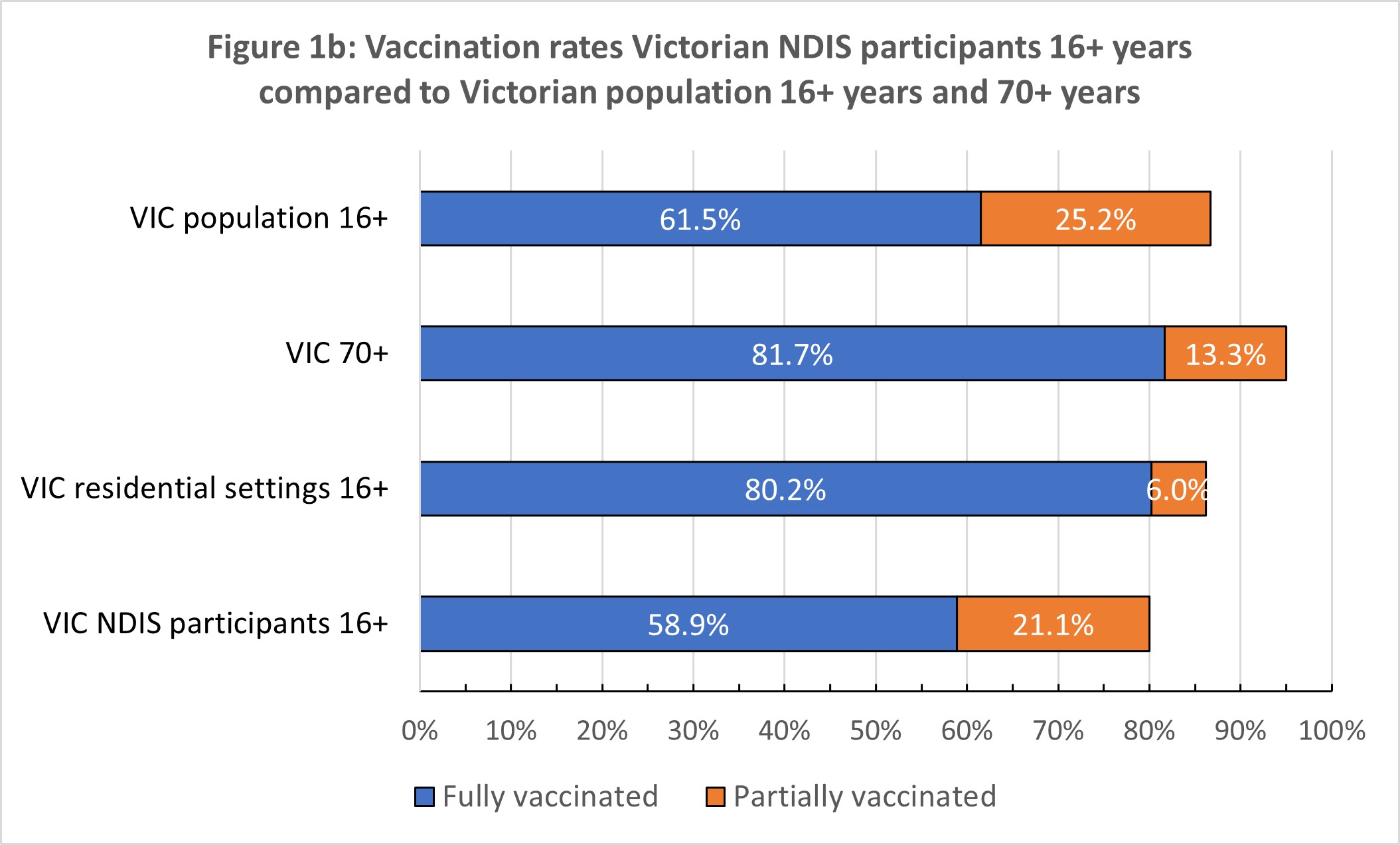

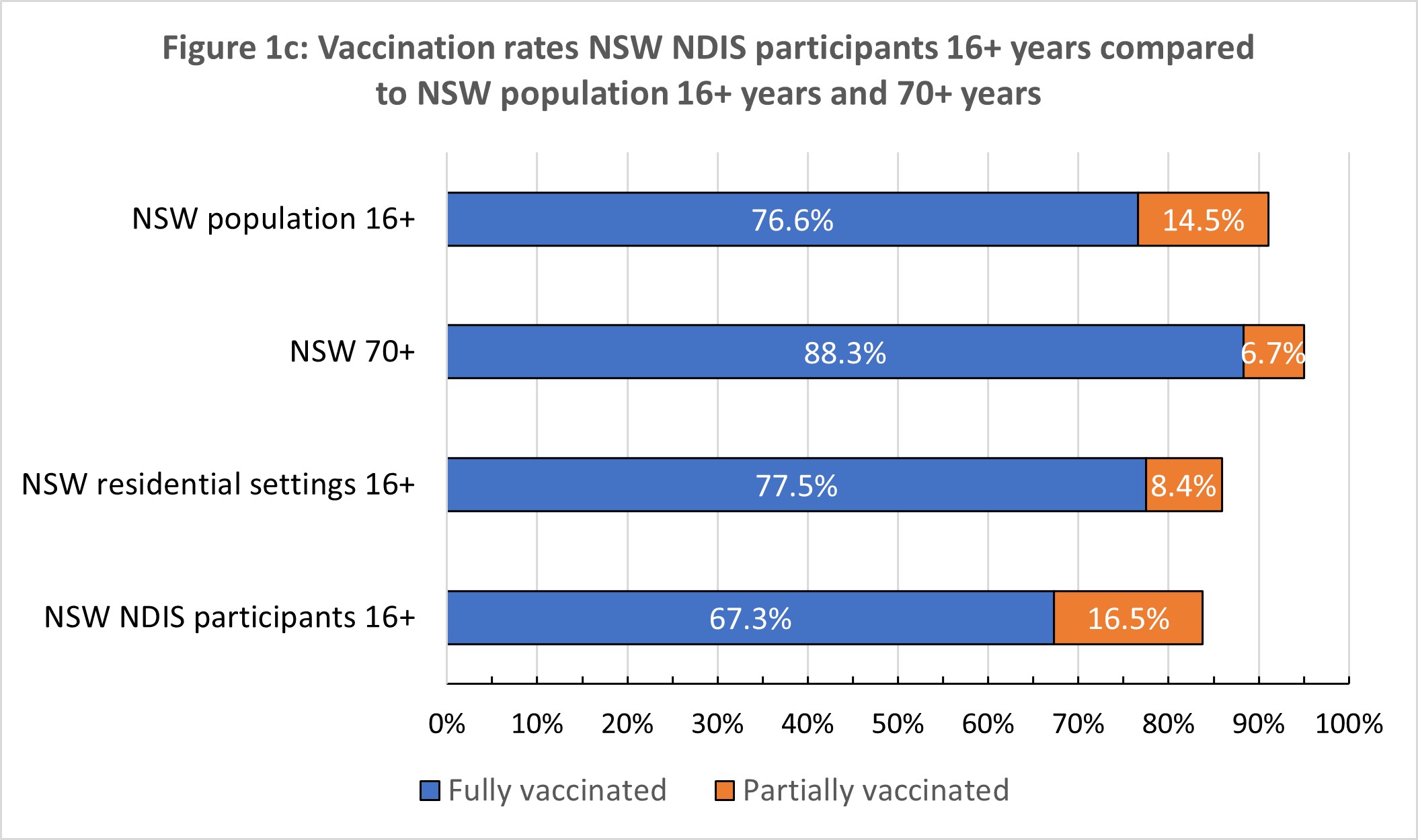

The most recent rates for all NDIS participants aged over 16 years (n = 267 526) were released by the Senator for the NDIS and relate to vaccination rates as of 12 October, and are shown in Figure 1 (a–c). Vaccination rates are compared with general population rate for Victoria and NSW for 12 October 2021 – the jurisdictions that have large caseloads and significant community transmission. We also compare vaccination rates for NDIS participants with people aged 70 years and older who were prioritised in Phase 1B.

Nationally, NDIS participants have at least one dose rate 8% below the national rate. Second dose rates lag by 6%. The gap in fully vaccinated NDIS participants is at least 25% lower than in Australians aged 70 years or over (the rate in this population is reported as >95%, so the gap could be larger).

Other than The Guardian newspaper, and recent government media releases, there has been no public reporting of vaccination rates across jurisdictions and local government areas and disaggregation by type of disability (eg, intellectual, autism, physical disability).

The lack of transparency and granularity in reporting of vaccination data makes it difficult to target vaccinations in particular areas with lower vaccination for people with disability and among people with different types of disability.

Have we achieved ethical and equitable vaccine allocation for people with disability?

Other than prioritising people with disability, Australia has comprehensively failed to meet ethical and equitable vaccine allocation for people with disability, according to internationally accepted frameworks supporting the findings of the Disability Royal Commission’s Special Hearing on the COVID-19 vaccine rollout for people with disability. Additional appointments, tailored outreach and communication and accessibility of vaccines have not occurred. The lack of quality data to monitor uptake reflects long-standing problems with disability data in Australia. For the data that are available, there has been a lack of transparency in reporting, which has meant that the government has not been held accountable for their failures, and it has been impossible to plan targeted outreach to unvaccinated groups of people with disability.

Where to from here for people with disability?

With NSW and Victoria about to remove restrictions with significant caseloads, there is no time to lose. We recommend:

- Commonwealth and state and territory governments provide resources to advocacy groups to provide tailored communication and, where necessary, advocacy groups organise appointments for people with disability experiencing barriers to access.

- Rapidly upscale accessibility through in-reach vaccination to settings where people with disability live, learn, work and recreate (eg, private homes, boarding houses, schools), and prioritise vaccination appointments through the eligibility checker and phone line.

- Increase the capacity of the Disability Gateway (provided through the Commonwealth Department of Social Services) to organise appointments for people with disability through a dedicated phone line, like the Disability Liaison Officers in Victoria.

- Provide regular reporting on vaccine rates across local government areas and type of disability on a public facing website.

- Set higher vaccination targets (over 90%) for people with disability, as has been called for by First Nations advocacy, medical and other expert groups.

Professor Anne Kavanagh, Centre for Health Equity, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Professor Helen Dickinson, Public Service Research Group, School of Business, UNSW Canberra .

Professor Nancy Baxter, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert