As governments seek to build public trust in nurses, allied health professionals and pharmacists, the role of general practice continues to pay the price for redistributed trust and investment.

Professionalism is about establishing and maintaining public trust. “The community trusts the medical profession,” states the Good Medical Practice guide, and “Every doctor has a responsibility to behave ethically to justify this trust.” Professionalism is often presented as an individual responsibility, but it is enabled and supported by structures and systems, including government policy and leadership.

Public health relies on public trust: it is difficult to persuade the population to adopt new health care behaviours unless there is a degree of trust in those who communicate health messages and manage health systems. This is why governments need to build trust in the health professionals they support, especially when there is a considerable change in the way health care is delivered.

The social contract between health professionals and society

There is a social contract between a professional and the community they serve. Society grants health professionals status, respect, autonomy in practice, the privilege of self-regulation, and financial rewards. In return, the community expects them to be competent, altruistic and moral, meeting the health care needs of individuals and society to the best of their ability.

At the moment, there are significant changes in the primary care sector, with health care reforms being proposed by various governments. The Scope of Practice review, the Review of General Practice Incentives, the Strengthening Medicare reforms and others are requiring the public to change the way they access health care.

Governments are readjusting their side of the social contract, changing autonomy, financial rewards and regulation, in an environment where there is already decreasing trust and respect for health professionals. In return, health professionals are assessing the other side of the social contract, and deciding whether they are still able to deliver competent, altruistic, moral care that meets the needs of their patients and their communities.

As the risks of practice rise, and the benefits decline, GPs are re-evaluating their roles and are leaving the profession at unprecedented rates. In particular, they recognise the risks of being held personally accountable for structural harms to their patients, a type of moral injury that is becoming more prevalent. Frankly, doctors describe being held ethically and legally responsible for systemic harm without the agency to counteract the personal and professional damage inflicted on themselves and their patients.

Principles underlying change

Governments clearly articulate the principles they believe underpin “good” care. All recent reforms claim to increase the accessibility, quality and efficiency of primary care, although there is also a less obvious goal to improve government access to primary care data. Strategies thought to address these goals include:

- encouraging co-located multidisciplinary team-based care. This is often presented as introducing team-based care, but in reality, most primary care patients already access bespoke teams, that are distributed across the community;

- extending the scope of practice of primary health care professionals;

- embedding technological innovations, data collection, data linkage and data reporting; and

- involving carers and consumers in system design.

These levers are not applied equitably, which exposes other agendas not obvious in the documents. For instance, the growth in health care technological entrepreneurship is a major concern, as well as an unprecedented opportunity. Doctors are trained to recognise and distrust conflicts of interest, which feature heavily in digital products and their marketing. Technological innovation is not subject to the strict evidence base that is expected of new drugs and devices, even though it is likely to have a significant impact on clinical decision making. An example of under-regulation is digital mental health products, such as cognitive behaviour therapy tools, which are excluded from the TGA regulation requirements, meaning most digital mental health products can sidestep regulation.

There are other concerns, including that these principles of change are not applied evenly across the professions. Perhaps this is because there are unconscious biases that ground the reforms, or perhaps there may be other agendas that influence the way these strategies are applied. Regardless, the impact is that the benefits and costs of reforms are changing the workforce, increasing the roles of nurses, allied health practitioners and pharmacists, while nudging GPs out of the primary care workforce.

This reorganisation of the workforce has been enabled by governments and other agencies redistributing public trust.

Building trust in nurses, allied health practitioners and pharmacists in primary care

Since the pandemic, governments have publicly supported, endorsed and promoted nurses, midwives, allied health practitioners and pharmacists, increasing their autonomy, agency and status. Various state and federal governments have increased financial rewards for these professions and championed their roles to increase public respect. Governments have used consistent language in these communications, describing nurses, midwives, pharmacists and allied health professionals as “highly trained health professionals” working at the “top of their scope”. The “top of scope” phrase is an effective rhetorical device to disguise the extension of scope into new areas of clinical practice. There would be no need for additional training if professionals already had the skills they are now using, but clearly programs like the pharmacy UTI trials have required training.

Examples of increasing government trust include:

Midwives, who are now indemnified by the federal government for home births and intrapartum care. Importantly, Minister Butler has removed the requirement that these births be classified as low risk, endorsing a midwife’s capacity to make that decision independently.

Midwives and nurses are now able to prescribe without the oversight of a doctor. The language of this announcement is important. “This is about supporting a workforce that is almost exclusively women”, states Assistant Minister Kearney “to empower them to become small business owners, to build their own practices and run their own clinics, so that more people get the care they need.” Minister Butler is even more frank. “Since gaining access to Medicare in 2010, nurse practitioners and endorsed midwives were the only health professionals required by law to establish an arrangement with a doctor in order to provide Medicare services,” Minister Butler states, “we can now see that this requirement has become a glass ceiling holding back our highly educated and highly valued nurses and midwives.”

By using the language of patriarchy and systemic misogyny, both Ministers simultaneously increase trust in nurses and midwives, while implying they have been “held back” by, presumably, the medical profession’s regulatory power and patriarchal attitudes.

Pharmacists are probably the profession that has benefited the most from these reforms, being funded and supported to deliver a range of extended services. Again, Minister Butler has endorsed, promoted and supported an increase in public trust for these initiatives and for the pharmacy profession as a whole. The language of “empowerment”, “top of scope”, “relieving the pressure on GPs and emergency departments” remains similar across these initiatives.

Decreasing trust in GPs

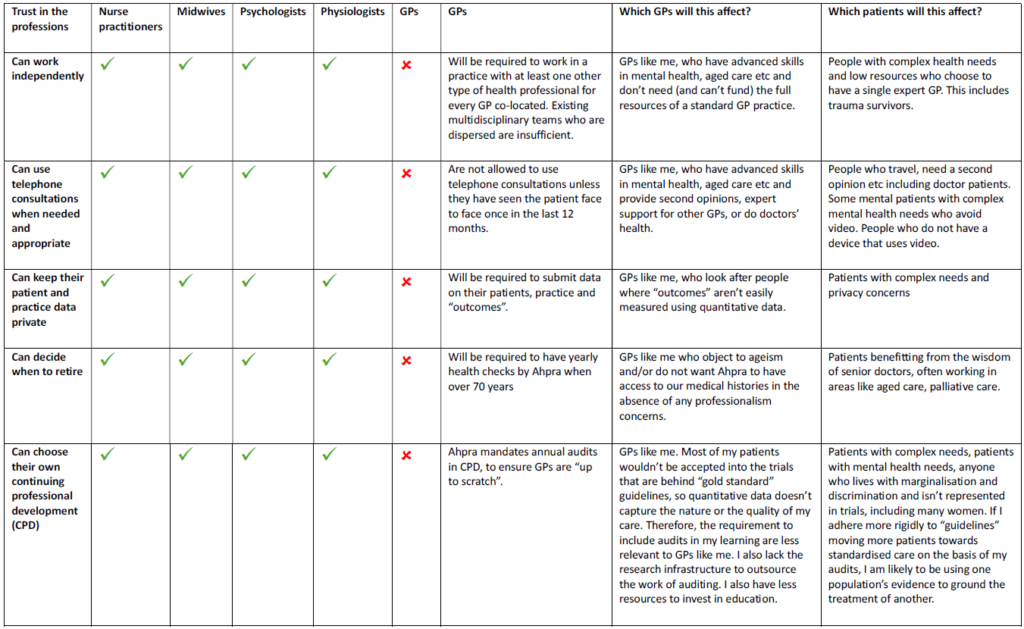

Table 1 demonstrates how governments, through current and planned reforms, reduce trust in GPs, and redistribute that trust to other primary care professionals. The policy levers are the same, but operate in the opposite direction, with decreased autonomy and financial reward, increased regulation and decreased respect. Frankly, the social contract for GPs is becoming untenable.

It is to be expected that highly trained professionals value their autonomy. Being unable to support patients, despite having the skills to do so, is the cause of moral injury, burnout and distress, and decimates the workforce, which partly explains the loss of GPs to practice in recent years.

Unconscious bias

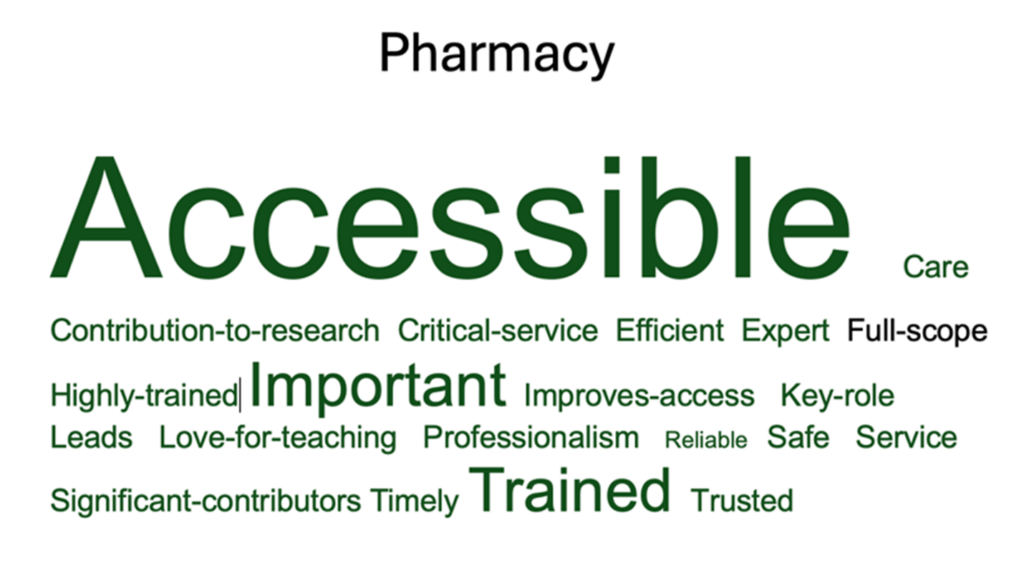

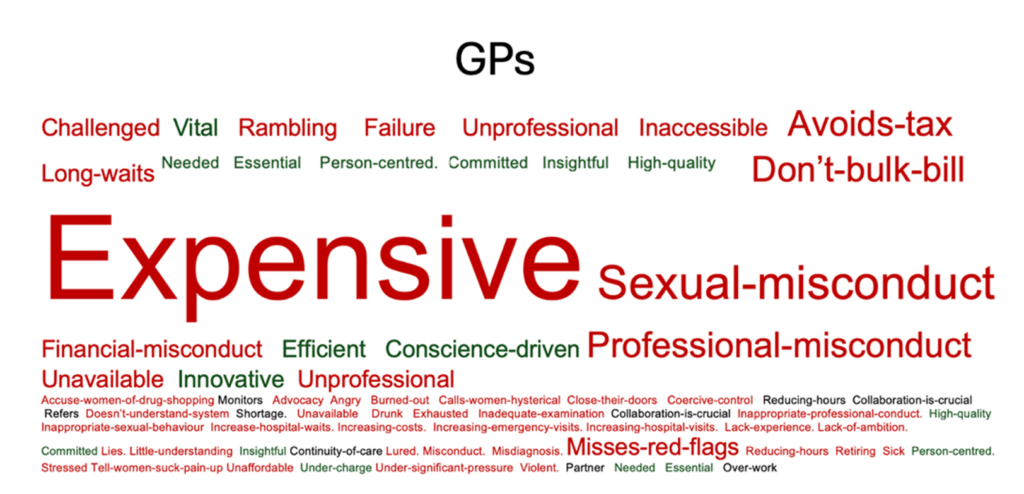

Despite the language of empowerment and respect, there are less obvious ways to diminish trust. In the ACT, there has been a sense that GPs have been sidelined in state government initiatives. To examine this, I undertook a study of ACT Health documents, analysing 430 000 words of ACT Health communications over a variety of media, including reports, social media posts, websites and Hansards. I then extracted the words used to describe the professions, and presented these in word clouds (see below). The results are disturbing, and demonstrate a system bias the redistributes government and public trust away from general practice. This may explain why ACT GP registrars experience twice the rates of bullying and harassment from the public and other professions than the national average.

Conclusion

At present, despite the rhetoric, there are clear signals that governments lack trust in the GP workforce. Without this trust, it is impossible for GPs to sustain the effective and efficient health care they are currently providing for the Australian community, which, in my view, is an extraordinary waste of a highly capable, efficient and effective workforce. There has been a sustained drop in investment in general practice year on year, and a clear redistribution of public trust, driven by government reform.

Perhaps it is time to analyse more carefully why reforms have been so uneven. We have long known the role of the social determinants of health in driving inequitable health care outcomes. With costs rising, and equity falling, it is important that all Australians consider the political determinants of health that also drive inequity.

Political determinants of health “involve the systematic process of structuring relationships, distributing resources, and administering power, operating simultaneously in ways that mutually reinforce or influence one another to shape opportunities” (Dawes, 2020). Manipulating public trust is one mechanism by which governments ensure a redistribution of relationships, resources and power. Using this lens, it is important to consider whether current reforms will achieve better outcomes, or whether the collapse of general practice will, in fact, cause considerable public harm.

Dr Louise Stone is a Canberra GP with clinical, research, teaching and policy expertise in mental health. She is an associate professor in the Social Foundations of Medicine group, Australian National University Medical School.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Associate Professor Stone’s article is brilliant – she has expressed articulately what many of us feel and perceive and gone on to back it up with well reasoned argument and fascinating data. What a great example of how intellect and research can inform worthwhile debate, hopefully guiding more thoughtful policy, Bravo!

An incisive summary of the current status of policy setting with regards to GPs .

Thank you Dr Stone , the Word Clouds are astonishing.

in reply to Louise Stone’s very valid comments, my point was that the Government is reacting to the GP shortages by empowering other to fill the gaps. ( mainly for minor or routine work ) In an ideal world, GPs would be always available to see acute problems , but with the modern medical workforce and practice structures this no longer seems consistently to be the case I absolutely agree that GP remuneration via Medicare has become untenable and successive federal governments have presided over this, turning a blind eye. But with the present situation I don’t see anything wrong, eg ,with having appropriately trained nurses in general practices dealing with routine things such as BP checks, vaccinations etc or being first port of call for some patients, with GP backup. in my experience practice nurses hey are very careful to with stay within their expertise.

Once again Professor Stone has done a great job in highlighting important issues facing general practice.

The “family doctor” GP was once a vital trusted service provided to individuals and society by the medical profession. Politicians and corporations seized the service for their own purposes and turned into a bulk commodity thereby undermining its ethical standing and trustworthiness. This dysfunctional disruption is associated with declining life expectancy as per ABS data, as well as unsustainable pressure on hospitals, so the sooner we revert to the trusted family doctor model the better.

Excellent article which articulates what many GPs are “feeling” I found the tables and word-clouds useful and illuminating. Thanks Louise.

Randal Williams has mentioned that we have to engage a variety of health professionals to replace the GPs because there are so few GPs left in the system. While this is one way of looking at it, it misses the deliberate policies that have caused GPs to leave. Phase one was bankrupting GPs by freezing rebates, and then expecting GPs to bulk bill. When the Health Minister asked people to “vote with their feet” if their GP doesn’t bulk bill, this was a tactic to shame GPs into donating time and labour on compassionate grounds. We already do compassionately bill, giving what is truly a 50% discount every time we do,

So, policy created the gap, and then used the gap to create a narrative around the necessity of extended scope. The Orwellian bit is when GPs are blamed for the shortage. It’s a masterful tactic, it’s just unfortunate for the community

Amazing article Dr Stone.

While I wholeheartedly agree with the all of the above, I think there is one aspect rarely mentioned – while most of us – at least at some point in our professional lives, and currently more often then not – would LIKE to leave in drones – the actual fact is – most of us can not and do not. What do you do if you have trained as a GP ? What would be a true equivalent for the things I have learned – and the things I have NOT learned but am aware about ….. I know of many colleagues, especially amongst the female GPs , that they would LIKE to leave – the majority struggles with the HOW. Some will find niche work – but the majority does not, is dependent on the income generated and hence keeps working with their heads down.Which then looks like a confirmation to politic makers that all is well , as the numbers leaving will not be drones. This in itself is a perpetuation of moral injury leading to working while starting to hate your job – one of the most sadest outcomes in a working life started with passion and love. I wonder how the young colleagues will fare under these circumstances with no true outlook of improvement – knowing that I will retire as soon as I can afford to. I worry about the mental health of these young aspiring GPs who have so much to offer for our patients and it makes me angry that there seems to be no support and no protection for this generation of young GPs.

Yes I remember the times when the Readers Digest “who do you trust the most” polls ,had GPs consistently in Number 1 position. Now we are lucky to retain 10th spot ;and always behind Pharmacists.

To what do we owe this demise in trustability, shown consistently by high attendance at emergency departments by patients seeking GP type attention; and the ” you are JUST a GP” comment frequently heard.

Could the following be contributory factors ?

Bulk billing and 6 minute medicines

Reliance on Polypharmceuticals

High non cure rates of patient complaints

Collusion between GP representative bodies and government

Conformity of treatments imposed by AHPRA and representative bodies

Lack of individuality amongst practitioners together with time restraint lack of compassion.

Lack of effective time with patients

High rates of mistaken diagnoses exposed by Dr Google

Does it really matter, because soon enough, primary care will be carried out by nurse practitioners, Pharmacists and AI.

I am grateful that I have been able to be a “doctor” for my patients during the last 53 years of GP practice ; and retire with the grace I have earned and deserve.

Thank you for writing this article. The word clouds are particularly arresting. There is no doubt that the undermining of General Practice over decades, & a failure to improve the public’s understanding of what GPs actually do, will have far reaching consequences. As you say, from a health economic perspective, a robust & well-supported primary healthcare system is significantly cheaper than the alternative. The federal-state cost-shifting (inclusive of demonisation of GPs!) kneecaps the health of Australians.

Wow! A brilliant piece of research. Food for thought for AMA and GP Colleges and individual GPs’ MPs, especially in rural and remote areas. We true believer GPs are being attacked on three fronts: Canberra, Specialist ownership of disorders eg ADHD and corporate medicine of the ‘one problem at one time’ variety. We must be the only profession where the better the care the lower the income. We may disappear, especially in the cities. And, in time, and with the input of health economists. we will be brought back again.

I have been in general practice for 66 years

I have had a wonderful professional life which included major surgery in hospitals and the delivery of over a thousand babies

I thank God that I am now able to retire with a clear ,happy conscience.

I wish my peers who will carry on the best of luck!!

I don’t agree with the author that this necessarily represents a loss of Government trust in the GP workforce, rather I believe it is an accessibility issue – what seems to be ever-decreasing prompt access to a GP for conditions that , even if not medically urgent are worrying to patients. I have made this point before in reply to various related Insight articles and will continue to do so. If GPs cannot provide the service the community needs ( for whatever reasons) then governments will look to empower others to fill the gaps ( nurse practitioners, midwives, pharmacists ) and these groups will be portrayed as competent, trustworthy and caring, as they mostly are. In my view , other than for routine appointments, a two-week or longer wait to see your own GP is not workable , and compares most unfavourably with general practice when I was a young doctor in the 1970s and 1980s. GP practices will need to address this issue ( and i know some are) if they want to remain the trusted first line for urgent cases or worried patients.

Great article. These trends are reflective of the current public discourse where truth is secondary to ideology.

It is difficult to highlight the obvious differences in training, aptitude (as measured by the rigorous requirements to enter medicine), and scope of practice in the current climate where unless you are a member of a minority or historically disadvantaged group, your views are attacked and dismissed.

In health utopia, we would celebrate the skills that each craft group has whilst recognising limitations, and work together to achieve the best outcomes for patients whilst feeling supported and valued. This is currently not the case and the direction Government is taking the health system is retrograde and ideologically driven and will very predictably result in loss of doctors and significant patient harm. The legal system will no doubt have a field day in the future which will result in health care ‘reform’ and recommendations for highly trained primary health care providers – the ones who are currently leaving in droves due to the untenable position created by Government attitudes and actions.

What we need is a public health marketing campaign to highlight what is happening to mobilise the public. and place pressure on Government. The last time this was tried, there was a a massive blow back and attack of ‘greedy doctors.’ How to get past this? There must be a marketing team out there who can rise to the challenge of preserving high quality health care in the interests of all. Let’s find them!

I have seen this loss of trust from patients for many years. Patients willingly pay big dollars to a homeopath, reflexologist, iridologist etc but refuse to pay a $10 co-payment to a GP. All the science and facts will not dissuade them. All these allied health people have managed to rise to the same status (if not exceed) of doctors. The next step would be for these people to directly refer to specialist and access hospital care. I feel like a coward but I am so thankful that I am now retired.

I am also deeply concerned by the systematic erosion of trust in general practice revealed in Dr Stone’s analysis. Her research exposes how government policy and rhetoric are rapidly undermining the foundation of our healthcare system – and ultimately, public health.

Every day, GPs manage complex chronic conditions, detect early cancers, support mental health, and coordinate comprehensive care for their communities. This work depends on trust – trust that is being deliberately redistributed away from general practice through carefully crafted government messaging and policy.

Dr. Stone’s analysis of 430,000 words of government communications reveals a disturbing pattern. While nurses, pharmacists, and allied health professionals are consistently described in positive, empowering terms, GPs are subtly portrayed as obstacles to progress. This isn’t just about words – it reflects a dangerous policy agenda that threatens continuity of care.

The consequences are already evident. GPs are leaving the profession at unprecedented rates, burned out by increasing responsibilities without corresponding support. When experienced GPs leave practice, they take with them decades of knowledge about their patients and communities – knowledge that cannot be replaced by fragmented care models.

Most concerning is how this undermining of general practice disproportionately affects our most vulnerable patients. Those with complex chronic conditions, mental health issues, or multiple medical problems benefit most from ongoing relationships with a GP who knows their history and circumstances. When government policy makes this model of care unsustainable, these patients suffer most.

Dr. Stone’s research exposes how political agendas masquerade as healthcare reform. While expanding roles for other health professionals may have merit, doing so by diminishing general practice is dangerously short-sighted. A strong healthcare system needs all professionals working together at their best – not one group being elevated by undermining another.

The solution isn’t complicated: we need honest recognition of general practice’s vital role, policies that support rather than undermine GP-led care, and public discourse that acknowledges the complexity and value of general practice. Our communities’ health depends on it.

Until then, every negative portrayal of general practice, every policy that fragments care, and every redistribution of trust away from GPs puts our healthcare system – and our patients – at risk. We cannot afford to stay silent while the foundation of primary care is eroded from within.

Good analysis

Illustrates the dumbing down, paradigm shift

I am one of the doctors “ retiring sick”

This is an excellent synopsis by Louise Stone who has called out and explained the surging fear and unease within medical general practice in particular- but it is actually intense and widespread across medicine overall.

The mutual trust and respect practicing medicine once enjoyed has been eroded. The forthright and demeaning rhetoric towards medical practitioners is pervasive and accepted as conventional logic -sadly.

If similar commentary were provided in respect of other providers, the high intensity chorus of disdain would be deafening.

The time is right within our representative organisations to re-ignite the awareness and perception in the community of the value of high performing GPs. By providing comprehensive, coordinated, continuity care that is a first point of contact that look after the community- despite systemic failures- improving and enhancing health, healthcare and wellbeing.

Each Medical Doctor has a role too – as a professional and as a thought leader – to explain and enunciate high standards and effective care that is the practice of Medicine which is complex, dynamic, evolving and ethical.

Calling out misinformation, untruths and politically motivated rhetoric is vital for the public’s health.

We must re-affirm the hard gained trust.

Dr Mukesh Haikerwal AC

General Medical Practitioner

Hi Good article. I’ve seen GPs disengaged as some PHNs haven’t actively engaged GP leadership development GPs a lot of them haven’t the medicopolitical language that GPs did have in Divisions.

Excellent coverage of this subject. Thank you Dr Stone