One thing is clear: primary mental health care must be at the heart of the next stage of national mental health reform.

THE future of primary mental health care will be a key challenge for the new federal government. Community demand for mental health care is far from satiated.

The Better Access Program began in November 2006, following on from the landmark Better Outcomes Program (funded initially in 2002), aiming to lift the number of Australians using primary mental health care services for mild to moderate mental health conditions, where short term evidence-based interventions are most likely to be useful.

Medicare spending on mental health services under the Program provided by GPs, psychologists and psychiatrists was more than $25 million every week in 2020–21. Given the magnitude of this public investment, it is important to track its progress.

Program architect Professor Harvey Whiteford and colleagues were able, in 2013, to find some evidence the Program has increased the rate of access of mental health care in Australia overall. More recently, the federal government increased the number of Better Access Program sessions per person from 10 to 20 annually at least until the end of 2022. The only formal government evaluation of the Program was in 2010. This evaluation found strong support from consumers for the Program, though respondents had been recruited by their treating health professional rather than independently sampled.

What has happened to Better Access?

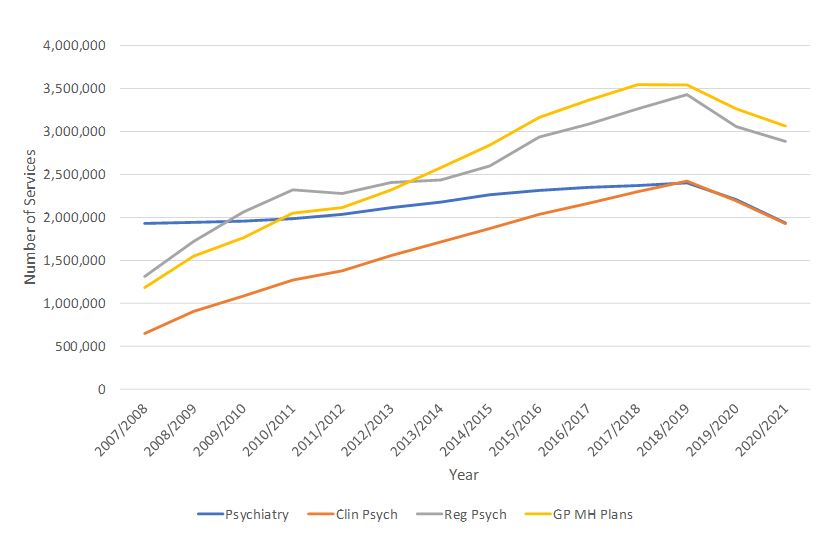

Since the introduction of the Better Access Program (first full year 2007–08), there has been a continuous increase in the delivery of services by clinical and registered psychologists as well as by GPs (Figure 1). By contrast, there has been a much smaller increase in services provided by psychiatrists. Our analysis of Medicare data (available online) shows that in total, 125.5 million services have been delivered at a cost of $13.5 billion over the period 2007–08 to 2020–21.

Figure 1 shows a significant interruption to this upward trend in face-to-face Medicare mental health services in 2019–20, during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented people from attending services in person.

Figure 1 – Better Access Program Face-to- Face Services 2007–08 to 2020–21

As telehealth services became more widely available under Medicare to compensate for this, the number of these services provided in 2020–21 more than doubled from the previous year, from 1.2 million to almost 3 million (Table 1).

Table 1 – Telehealth Services 2019–20 and 2020–21

| Service type | 2019–20 | 2020–21 |

| GP mental health treatment plan (telehealth service) | 21 635 | 35 353 |

| GP mental health treatment plan (phone service) | 280 314 | 723 945 |

| Consultant psychiatrist telehealth services | 103 597 | 294 270 |

| Consultant psychiatrist phone services | 159 870 | 413 651 |

| COVID-19 Clinical Psychologist psychological therapies telehealth services | 231 611 | 495 978 |

| COVID-19 Clinical Psychologist psychological therapies phone services | 112 817 | 205 388 |

| COVID-19 Registered Psychologist focused psychological strategies telehealth services | 194 213 | 478 323 |

| COVID-19 Registered Psychologist focused psychological strategies phone services | 138 704 | 274 190 |

| Total | 1 242 761 | 2 921 098 |

Source: Medicare Group Statistics Reports, online database.

Taking these increases in telehealth services into account, the overall upward trend in Medicare mental health service delivery, while now bifurcated between face-to-face and telehealth care, remains clear.

Whereas the number of services may be increasing, the number of clients receiving care is less clear. The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services shows that the proportion of clients who were new to the Better Access Program was 36.6% in 2012–13 but only 29.2% in 2020–21. The majority of service users are therefore repeat patients seeking ongoing support.

This trend prompts questions not only about the impact of the Program but also in relation to overall program design. Specifically, these data raise the possibility that Better Access Program services are not being provided for “short term” interventions as originally intended, but increasingly for users with more complex, longer term needs. In the absence of definitive outcome data, questions have been raised about the Program’s effectiveness.

The most recent changes in the operations of the program introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic in response to the surge in demand have placed further emphasis on the provision of extended care rather than making it easier for more Australians to find mental health care. It is also noteworthy that GPs wrote more than 1.2 million mental health plans for Australians in 2020–21 but of these, only just over one-third (36.8%) were reviewed, meaning patients’ progress was largely unmonitored by their GPs. Without monitoring, it is not possible to discern if a person’s mental health is improving or worsening and plan next steps appropriately. It also removes an important element of systemic accountability.

Constraints and issues

There are workforce constraints with limits on working hours and the overall number of professionals. Paradoxically, this might mean that recent federal government funding that increased the number of sessions available per person may actually decrease the total number of people able to access the program, perversely making public access worse for some, not better. This situation is most acute for psychiatry services, where growth under the Better Access Program has been appreciably slower than among the other professional groups.

We know that out-of-pocket costs associated with the fee-for-service model under which the program operates deter people from seeking care. Simply making more sessions available does nothing to alleviate this burden.

This analysis and commentary around the Better Access Program should be seen in the context of recent recommendations for its reform and better targeting made by the Productivity and Victorian Royal Commissions, as well in the earlier comprehensive review undertaken by the National Mental Health Commission in 2014. They all suggest that the most effective way to organise primary mental health care is on a region-by-region basis, creating opportunities for state and federal agencies to work more closely together, pool funding and conduct joint planning.

Participants in the recent Sydney Mental Health Policy Forum expressed their strong support for structural reform in mental health, including for multidisciplinary approaches combining clinical and psychosocial care in new ways particularly to meet the needs of people with more complex mental health problems. For these people, repeatedly going to see the same clinician working alone may be insufficient to address their multifaceted needs. For example, a person with an eating disorder may well benefit from a coordinated team comprising a GP, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a nurse, a dietician, and other allied health support plus peers.

Where to now?

There are new “bilateral” agreements in place between the federal government and all states and territories. The publicly available information on these agreements does not suggest they involve either a significant shift to greater regional control of funding and planning, nor better targeting of the Better Access Program as part of more general primary mental health care reform. Both the Victorian and the federal government are working to establish new community mental health clinics, but how these relate to each other and to the task of primary mental health reform is unclear.

A second federal government review into the Better Access Program is underway and was due for completion in June, with findings expected any day now. It represents an important opportunity to recalibrate the program around its initial mission to increase public access to primary mental health care and to consider related issues such as quality and value for money, as well as to ensure other services are available for people needing more than short term mental health interventions. This work must be central to the structural and strategic reform of mental health, as a priority for the incoming Labor government.

There are four obvious focal points for this recalibration.

First, consideration must be given as to how to increase access to specialist assessment and short term interventions, along the lines originally envisaged for the program.

Second, there is a need to develop practice incentives that support provision of services under the program to disadvantaged and other groups currently missing out. This would include economic, social, geographic and cultural groups.

Third, there is clearly a need for new incentives to support active review of patient plans. This is core to program accountability.

Finally, there is a need to develop and promote the use of new technologies to support more effective triage, assessment and review of patient progress.

The federal government is clearly thinking about the future of telehealth right now. One thing is clear: primary mental health care must be at the heart of the next stage of national mental health reform.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg is a Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney.

Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director of the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney. He is a member of the Clinical Advisory Group for evaluation of the Better Access Initiative.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Ian Hickie has held a consistently negative view about general practice for several decades. I provide specific mental health care to a group of patients as well as being a regular general practitioner. If I want to find a psychiatrist who will bulk bill my pensioner or poor patients I cannot, because there are almost none that I know of. I don’t do reviews of MH treatment plans because I simply ask my patients how they are feeling, sometimes rechecking their DASS scores and always discussing the symptoms that might recur and bring them back to have psychological care again if needed. Over the period of time they are seeing me we discuss the value of regular exercise, relaxation and slow breathing techniques, triggers for their depression and anxiety as well as prescribing or not prescribing medication. A number of my patients have been through the psychiatrist – psychologist mill and not been helped. Those people are a pleasure to look after because I can’t do any worse than the psych-psych mill! Government health departments love the “Hickies” of the world – counting billing numbers and being dismissive of GPs without considering the positive impact GPs have on the lives of millions of people in Australia.

I am a GP. This article suffers severely from a lack of understanding about what happens in general practice. It should have had at least one GP as a co-author. The authors should take note of the comments from my GP colleagues, and hopefully in future will discuss any further statements or reports that they propose to publish with appropriate GP colleagues.

My GP colleagues have already provided eloquent responses to the above article, especially sadly that Professor Hickie and Dr Rosenberg appear to misunderstand completely how we work and how we bill- it is disappointing that they have drawn such erroneous conclusions on this basis as a platform for proposed reform . I would suggest that GPs are expert in triage, assessment and review of their patients’ mental health presentations and are hamstrung by lack of time and inadequacy of support services to demonstrate this adequately. We are already embedded locally and funding us and our practices better as the most effective and value for money services would be preferable to funding more bricks and mortar centres. Short term interventions are available and accessible and GPs are agile and able to help patients access these. What we struggle to access is tertiary services both publicly and privately – perhaps the esteemed Psychiatrists could attend to this by working towards removing the myriad barriers such as as exorbitant cost, workforce issues and extremely restrictive referral criteria as well as often non trauma-informed practices which makes it difficult for us and our patients to work collaboratively with them.

Additionally if they would like to learn more about the barriers for GPs in provision of mental health care in our practice I would refer them to this recent excellent report by GPMHSC: https://gpmhsc.org.au/getattachment/7be109a5-d32f-48c5-bf33-6c16c12e689b/delivering-mental-health-care-in-general-practice_implications-for-practice-and-policy.pdf?fs=e&s=cl

Not claiming a review of a GP mental health plan does not mean that the GP has not reviewed the patient’s mental health. Such statements reflect ia lack of understanding of the complexities of general practice and the patient-doctor relationship. Medicare items do not reflect the actual continent of a consultation. GPs apply “whole of person care”. How many psychologists and psychiatrists are out there providing home visits??

I see some kernels of “truth” in the opinions expressed by Rosenberg and Hickie and it’s my anecdotal view also that fewer patients are accessing more treatment sessions. It seems inevitable that this would be attractive and simpler for clinicians who are enabled to manage fewer patients for longer treatment periods and this is more intensive treatment approach is actually good practice for complex issues, albeit not necessarily holistic and multidisciplinary as the situation often requires. This advantages patients who can afford considerable gap fees (and could potentially make it easier for providers to be more “selective” of who they treat) while disadvantaging those unable to pay gap fees or access technologies for Telehealth.

It clearly makes sense that fewer mental health reviews are performed by GPs if the experience of the majority of patients is that they have less than 5 or 6 sessions with a psychologist and therefore see little value in a mental health review consultation with their GP, especially when the impression that has unfortunately and insidiously evolved is that reviews are only necessary to access further sessions with a providers, rather than a helpful clinical review of their symptoms and concerns. GPs regularly recommended review appointments but patients choose if, when and why they return. We commonly review patients mental health without the use of mental health specific item numbers, often to destigmatise the consultation as part of a holistic approach and this remains unmeasured and unacknowledged by the bean counters.

These systemic MBS issues definitely, in my opinion, need to be reviewed in order to provide the greatest good for the most number of people.

Finally, what also stands out for me is the lack of accuracy in the measurement of provision of GP mental health services , especially counselling and psychotherapy services as the specific mental health item numbers available to GPs are frequently disadvantageous to utilize(for both GPs and patients) compared with regular time based item numbers where rebates are higher. It is highly sad and ironic that the combined freeze and cutting of the rebate on item 2713, initially introduced to incentivize and encourage GP mental health care provision by a very modest 10% increase in value compared with item 36, has now resulted in the absurd situation where mental health care is literally undervalued compared with physical health care presentations.

Figure 1 shows a steady increase (until COVID) in a parallel pattern between psychology, GP and psych reg services, but a flat line in psychiatry. Do we need more psychiatrists in the public system to increase accessibility?

Regional NSW GP here – My socioeconomically disadvantaged mental health patients can no longer afford to see a Telehealth psychiatrist as they are now billed a gap fee. GPS are seeing most of the severely chronic mentally ill with minimal or no genuine psychiatrist backup. Community public specialist psychiatric services are extremely underresourced & undermanned, just an empty shell of a community service.

“It is also noteworthy that GPs wrote more than 1.2 million mental health plans for Australians in 2020–21 but of these, only just over one-third (36.8%) were reviewed, meaning patients’ progress was largely unmonitored by their GPs. Without monitoring, it is not possible to discern if a person’s mental health is improving or worsening and plan next steps appropriately. It also removes an important element of systemic accountability.”

This is an embarrassingly misinformed view. It shows a complete lack of understanding of mental health management of patients in primary care and the relevant item numbers.

I suggest the authors talk to GPs about how item 2712 is not a necessary component of reviewing and supporting patients with mental health issues or mental health care plans.

Billing patterns are not a proxy for GP behaviour, so your conclusion that a third of patients with mental illness are not being reviewed is flawed. I also find it fascinating that you haven’t highlighted the huge gap fees that some psychiatrists are charging? This is the biggest single barrier to specialist care IMHO and the reason why GPs are having to manage increasingly complex mental illness

A GP (or a few GPs within a group practice) develop a long term relationship with their patients. They deliver whole of body care, including mental health care. Each episode of care, usually entails discussion and review of multiple systems, and questions about the patient in the context of their life/family/environment. The billing of item numbers will never reflect this complex relationship. I’d hope the authors are well aware that mental illness occurs with & alongside physical illness. GPs often do not, and cannot separate the treatment of each into silos, instead we deliver the required care as it is needed. I would argue that as we compartmentalize health care, access gets more difficult, as each part has extra criteria to meet to get access. Sure, focus on item numbers to prove your political point, and fund your large shiny organisations. But know the GPs are the most accessible, efficient, and skilled mental health care practitioners on the ground, delivering the majority of the care. Unrecognised.

There are three common misconceptions in this article.

The graphs for GPs are based on the item number billed, not the activity undertaken. GPs are doing more mental health than ever, but we don’t always use a Better Access medicare number when we do,. The graph shows a small subset of our work; how we bill is not a measure of mental health activity in General Practice. Many patients prefer it if we use a consultation rather than a mental health item number.

On a related note, this is not new investment in General Practice mental health. A complex mental health consultation of 30 minutes billed with a normal consultation item number offers a rebate to the patient of $76.95. A complex mental health consultation of 30 minutes billed with a Better Access item number offers a rebate to the patient of $75.80. There is less investment in GP mental health through Better Access than there ever was. We have always done this work. Occasionally, now, we bill it differently. But the cost to the community through Medicare has not changed.

Given the complexity of a MHTP review MBS criteria, many of us do not use the 2712 item number. We are not required to bill a 2712 when we do a review. So it is impossible to estimate the number of reviews done using Medicare data. It is perfectly possible to conduct a review, bill a normal consultation item number and circumvent the complex MBS billing rules involved in using the 2712. So again, it looks like there is no review of mental health plans.

I do, however, agree about the complexity. Frankly, I will use any mechanism possible to get my patients the care they need. I don’t think we ever focussed on “simple depression and anxiety”: there isn’t time between all the patients needing complex care.

It is always helpful to involve a GP when writing about the activities undertaken in General Practice. As you know, interpreting Medicare data from a generalist profession is fraught with misinterpretation. Before we recommend that there should be more “incentives to encourage review” perhaps it would be helpful to talk with GPs about why they do what they do. We are becoming increasingly tired of being told by other health professionals how we could improve our practice and benefit our patients. We are happy to discuss the complexity when we are included in the conversation.