THINGS move fast in the world of COVID-19.

On 25 May 2021, we published an issues brief for the Deeble Institute on the long term health consequences of COVID-19 in Australia.

Since then, much of the country has experienced fresh lockdowns, most recently in Sydney. These outbreaks appear to have given a much-needed jolt to previously lacklustre demand for COVID-19 vaccination across the nation. Yet the vaccination program itself has required further modification as expert advice and political messaging on age recommendations for the AstraZeneca vaccine changed yet again, and supply issues have driven a new, four-phase National Plan which implicitly recognises that high levels of vaccination will not be reached for many months.

Overseas, the World Health Organization is worried by the Delta variant and rising case numbers even in nations with higher vaccination rates. In England, the government is pushing ahead with ending restrictions on 19 July even as new daily cases mount into the tens of thousands, on the basis that deaths and hospitalisation rates are now much lower than in previous waves. Meanwhile, evidence on the scale and burden of “long COVID” and other post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 has continued to accumulate, with a number of significant studies and media articles published in the past few weeks. Now is a good time to take stock of this emerging evidence on the longer term health consequences of COVID-19, and to consider what it means for the Australian health care system.

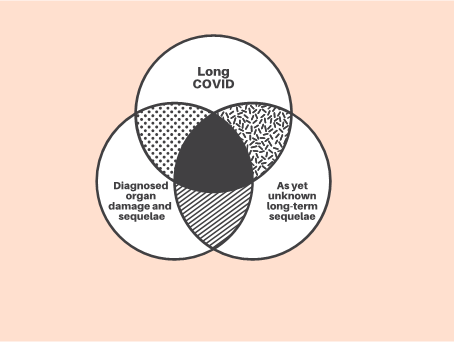

Our issues paper summarises what is known about the post-acute conditions being diagnosed in patients who have survived COVID-19 infection, and identifies three areas of ongoing focus for the health care system (see Figure).

Source: Hensher, Angeles, de Graaff, Campbell, Athan and Haddock, 2021. Reproduced with permission of the Deeble Institute for Health Policy Research

Many patients who have been hospitalised with severe COVID-19 infection appear to have suffered a range of concerning sequelae affecting multiple organ systems, including lung and cardiac damage – in addition to the debilitating impacts of post-intensive care syndrome affecting many of those who required ICU care.

Meanwhile, large numbers of COVID-19 survivors – including many who suffered only mild illness during their acute infection – report suffering from persistent fatigue and a range of symptoms that have come to be known as “long COVID”. A recent piece by a team investigating and caring for patients with long COVID in Melbourne describes the Australian clinical experience with long COVID clearly and succinctly.

Yet, less than 18 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the history of previous viral pandemics suggests that we should also be on the lookout for other longer term sequelae that may not yet be visible: for example, the neurological complications that are believed to have impacted some Spanish Flu survivors, often many years later.

We reviewed the rapidly growing literature on the prevalence of long COVID and other post-COVID sequelae. This literature is a complex mix of small clinical cohort studies, larger analyses of electronic health record datasets and – in the case of the UK, at least – very large population surveys. While the clinical cohort studies generate higher estimates than other methods, all approaches suggest that a surprisingly large proportion of people experience clinically and socially meaningful post-acute symptoms, and, for significant numbers of patients, these can endure for many months.

Based on this literature, we estimated that there might have been between 2800 and 5400 people with some long COVID symptoms in Australia in April 2021. Most of these cases (2000 to 3700) were likely to be concentrated in Victoria, which has been home to the largest Australian outbreaks.

In the weeks since our issues brief was published, more evidence has continued to emerge.

The latest update of the UK ONS survey series estimated that, in May 2021, some 376 000 people across the UK continued to experience long COVID symptoms for 12 months or more – up from 70 000 people in March 2021, clearly reflecting the UK’s major first wave infection peak in April 2020.

A large US study of private health insurance electronic records found that 23% of patients who had a COVID-19 infection had recorded post-COVID conditions.

Just as important as this additional evidence on prevalence was a first attempt to model the burden of post-COVID illness in both Pakistan and the UK using disability-adjusted life years, reported in Nature, which suggests that post-acute illness and disability could account for 30% of the total disease burden of COVID-19.

We provided a number of recommendations for the Australian health care system on how to prepare for and manage long COVID:

- prioritise primary prevention but prepare plans in advance to allow rapid scaling up of care for the long term sequelae of COVID-19 infection;

- establish a national centre of excellence for post-COVID care with regularly updated clinical guidelines, along with care coordination centres in each state and territory;

- establish a nationwide COVID-19 registry for long term surveillance and follow-up of sequelae;

- research and model the morbidity burden of long COVID and post-COVID sequelae; and

- ensure that Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme safety net measures adequately mitigate out-of-pocket costs for long COVID and post-COVID patients.

We concluded that primary prevention of COVID-19 infection remains the most effective means of mitigating the long term consequences of the pandemic in Australia. Even with the new National Plan, Australia’s slow pace in vaccinating a population which has overwhelmingly not been exposed to infection means that this country will remain vulnerable to a major outbreak for many months to come. At some point, separation from the rest of the world will no longer be sustainable; if a significant proportion of Australians remain unvaccinated by choice at this time, then some larger outbreaks are probably unavoidable, and with them will come post-COVID sequelae.

The growing evidence on the burden of long COVID and post-COVID sequelae has not typically figured in modelling and discussion of control measures, yet it is increasingly clear that this long term burden is now significant in those countries which have experienced high rates of infection.

Acknowledgement of the scale of long COVID does not change the actions we need to take to prevent COVID-19; but it is highly relevant to discussion of the thresholds, triggers, risk– and cost–benefit trade-offs that should be considered as control measures are tightened or loosened in response to changing epidemiological data. It also seems reasonable to suggest that future pandemic planning should take more seriously the burden of post-acute illness in survivors, drawing both on the lessons of COVID-19 and the longer history of pandemics.

In many of the high income countries where large numbers of post-COVID patients are presenting with wide-ranging symptoms, the typical health service response has been to develop dedicated, multidisciplinary long COVID clinics. These are now widespread in many countries; indeed, the English NHS is now opening 15 dedicated paediatric long COVID hubs, in recognition of the growing burden of this condition in children and teenagers.

A handful of adult long COVID services have been initiated in Australia, primarily in Melbourne and Sydney. However, given our current fortunate position, the likely nationwide distribution of long COVID cases probably does not warrant dedicated services in every state and territory.

We recommended instead that a national post-COVID care Centre of Excellence be established, which would provide guidance and authoritative information; and that each state and territory establish a statewide care coordination centre to mobilise public and private sector resources to ensure effective local access to multidisciplinary care, and to provide a model for care coordination in other complex chronic conditions. If Australia’s control measures – or our luck – were to break down, this infrastructure would provide a core from which to support rapid scaling up of services (including dedicated long COVID clinics) if required.

Ensuring that we can monitor and measure the long term sequelae of COVID-19 is also essential to any effective response. We recommend the establishment of a national data registry and data linkage capability (noting that work on some aspects of this task is under way by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) to enable long term follow up of every Australian resident who has tested positive for COVID-19.

Such a capability potentially allows Australia to lead the world in surveillance of post-COVID illness, and would be particularly important for monitoring the emergence of any as yet unknown long term sequelae, and changes in the health status of those who have suffered organ damage or impairment as a result of COVID infection. Such surveillance equally needs to guard against the risks of overdiagnosis and over-medicalisation in COVID survivors.

Caring for those suffering the longer term consequences of COVID-19 – whether in smaller or larger numbers in future – may also present an opportunity for new approaches in an area which Australia’s health care system has long found challenging: providing integrated care for people with complex chronic conditions.

We considered a number of approaches to value-based health care which might assist here. However, long COVID has also illustrated a deeper challenge which will need to be overcome.

The complex mix of fatigue, physical and psychological symptoms seen in long COVID has touched a raw nerve; some clinicians have come perilously close to saying (or in some cases have said outright) that long COVID is a psychosomatic condition. The similarity of some long COVID symptoms to those seen in myalgic encephalitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) has been noted; and many patients with long COVID, like patients with ME/CFS before them, are expressing strong concerns that health professionals are not taking their conditions seriously, if not actively stigmatising them.

The sheer scale of COVID-19 in many countries means that a movement of long COVID advocates who are themselves simultaneously patients, clinicians and/or health researchers is pushing hard to ensure the condition is taken seriously, in a manner not entirely dissimilar to the early days of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

What is certainly the case is that many post-COVID patients perceive themselves to be significantly unwell and are demanding care; while health professionals are struggling with the absence of any definitive treatment that will rapidly or reliably improve their symptoms. The “psychosomatic” criticism might as readily be levelled at those health professionals who are unable or unwilling to engage effectively with patients for whom they cannot offer simple, definitive and curative interventions. Yet this challenge is not new; it is what makes the routine care of many chronic conditions, not just ME/CFS, complicated and frustrating for professionals and patients alike.

Even if Australia successfully dodges the bullet by avoiding a large burden of long COVID care, this structural and cultural weakness within the health care system will still need to be addressed.

Martin Hensher is Associate Professor of Health Systems Financing and Organisation at Deakin University’s Institute for Health Transformation, and Deputy Director of Deakin Health Economics.

Mary Rose Angeles is a Research Fellow in the Health Systems Financing and Sustainability team at Deakin Health Economics.

Barbara de Graaff is a Senior Research Fellow at the Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania. Her research has explored the equity and economic dimensions of a range of diseases including hepatocellular carcinoma, ME/CFS, HFE haemchromatosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Julie Campbell is a Research Fellow at the Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania. Her research has explored the health economic burden of complex and chronic disease areas including multiple sclerosis, ME/CFS, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Eugene Athan OAM is Professor of Infectious Diseases in Deakin University’s School of Medicine and Director of the Department of Infectious Diseases at Barwon Health, Geelong.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Long term follow up of people who were hospitalised with SARS-CoV-1, MERS and Ebola supported figures from Australia’s 2006 prospective Dubbo study: roughly 10% conversion to ME/CFS.

There seems no reason to anticipate that COVID-19 will be different.

Services for Long Covid should be codesigned with those who have lived experience of ME/CFS.

Further, those services should also be offered to those already living with ME/CFS. In Australia that may be up to 260,000 people living with a chronic illness that leaves approximately 25% of them homebound due to disabling symptoms.

Thank you for this article, and I concur with the other comment regarding the mention of ME/CFS. As an active researcher on ME, in collaboration with a number of Australian and OS colleagues, my view is that the cases of long-COVID that cannot be explained by post-acute tissue/organ damage are in fact ME, this time triggered by a new virus. My advice is to leverage from the ME research to help understand long-COVID; let’s not “reinvent-the-wheel” through seeing this as a separate condition.

Thanks also for mentioning the unfortunate attitude of some medical practitioners who lazily assume that the condition is psychosomatic – leading, as you said, to further grief in patients who feel humiliated and rejected by the health system. The aetiology is physiological, right down to cellular, immune and mitochondrial function.

Wow, thank you for actually mentioning ME/CFS!

It’s disgusting though to those of us who have battled with it for decades (23 years in my case, since I was 14) to suddenly see so much help offered to Long COVID-19 patients, when essentially, they have the same thing as us, & we’ve been called lazy & crazy for so long….

As someone who dreamed of being a veterinarian from the age of 5 (later I realised vet nurses were cooler), lazy is the last word to describe me….

We also need to develop a STRATEGY on how we are going to immunise younger age cohorts given what we’re seeing in Europe and US with this age group and community transmission and post vaccination “complications”. A strategy folks, not a blame game, shell game, supply game, or military exercise. A clear actionable plan that enables every stakeholder to understand what’s happening not read about it in a press release and have to answer 10 thousand calls.