THE National Heart Foundation has cautiously endorsed the use of coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring for the assessment of cardiovascular risk in certain populations and under certain conditions, in a new position statement published by the MJA.

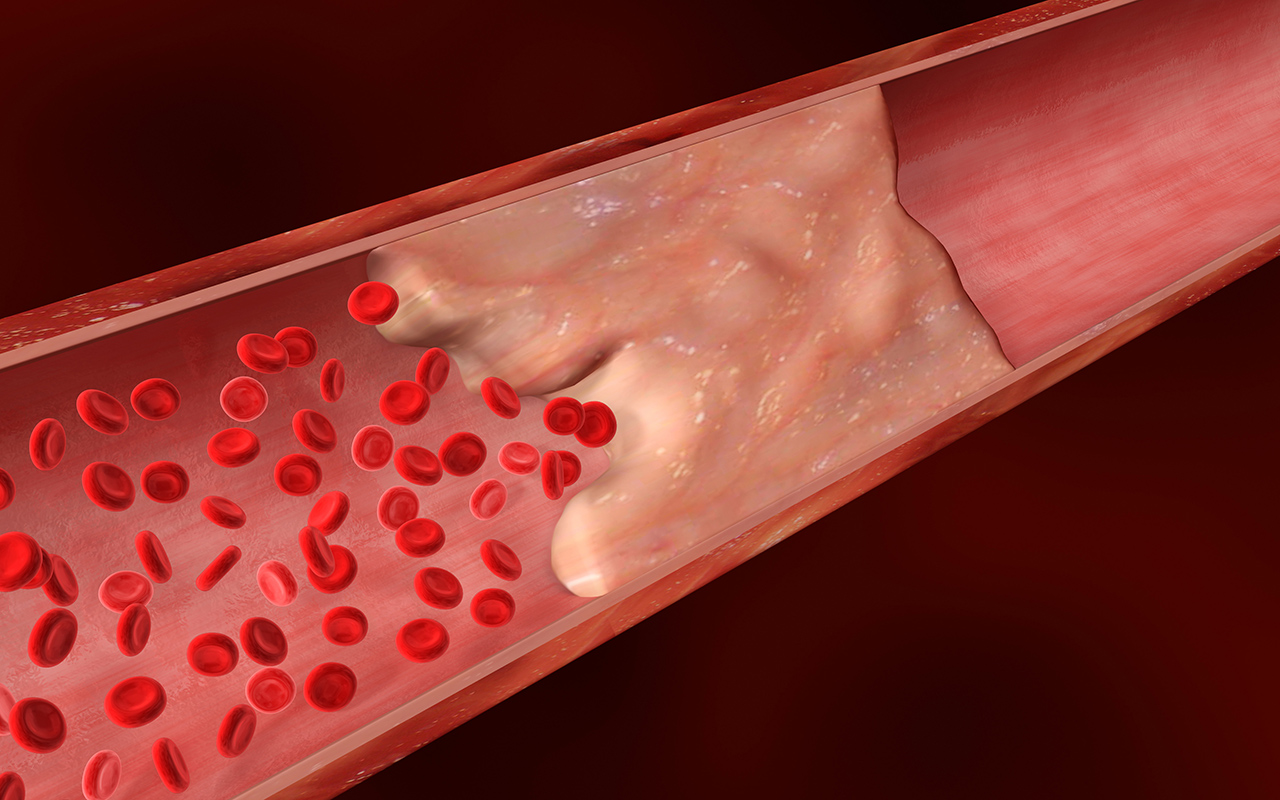

CAC scoring measures the amount of calcium in the coronary arteries from a computed tomography (CT) scan of the heart. A positive CAC score, measured in Agatston units (AU), is a marker of atherosclerosis, with increasing CAC scores correlating to increasing risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and a CAC score of 0 AU indicating an absence of CAC and a low risk of CVD events.

“Evidence for the ability of CAC scoring to improve the predictive performance of traditional risk assessment models, and for the ability of CAC-guided management to reduce CVD morbidity and mortality, is evolving,” wrote the authors of the position statement, led by Professor Garry Jennings, Chief Medical Advisor of the Heart Foundation.

The authors made the following four recommendations:

- CAC scoring could be considered for selected people with moderate absolute cardiovascular risk, as assessed by the National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance (NVDPA) absolute cardiovascular risk algorithm, and for whom the findings are likely to influence the intensity of risk management. (GRADE evidence certainty: Low. GRADE recommendation strength: Conditional.)

- CAC scoring could be considered for selected people with low absolute cardiovascular risk, as assessed by the NVDPA absolute cardiovascular risk algorithm, and who have additional risk-enhancing factors that may result in the underestimation of risk. (GRADE evidence certainty: Low. GRADE recommendation strength: Conditional.)

- If CAC scoring is undertaken, a CAC score of 0 AU could reclassify a person to a low absolute cardiovascular risk status, with subsequent management to be informed by patient–clinician discussion and follow contemporary recommendations for low absolute cardiovascular risk. (GRADE evidence certainty: Very low. GRADE recommendation strength: Conditional.)

- If CAC scoring is undertaken, a CAC score > 99 AU or ≥ 75th percentile for age and sex could reclassify a person to a high absolute cardiovascular risk status, with subsequent management to be informed by patient–clinician discussion and follow contemporary recommendations for high absolute cardiovascular risk. (GRADE evidence certainty: Very low. GRADE recommendation strength: Conditional.)

Speaking in an exclusive podcast, Professor Jennings acknowledged that despite the low grade and weakness of the evidence, CAC scoring was being used by clinicians and it was appropriate to provide guidance.

“Many clinicians are finding CAC scoring extremely useful in their practice,” he said.

“That’s why [writing the position statement] was a fairly difficult process because we did have some diversity of opinion.

“Some people were saying, we are already using it and finding it helpful. Other people said there’s no randomised control trial that shows that people do better if they have this test compared to being managed in the conventional way.

“So it did need to be reconciled, and I believe this position statement does that.

“The other context is that if [CAC scoring] is in widespread use, it’s important that that there is something out there that represents the best expert opinion that we could assemble,” said Professor Jennings.

“There are lots of things we do in health, new medicine, which may not have a really strong evidence base, and you’ve just got to make a call sometimes as to how we handle the here and now.”

Jennings and colleagues acknowledged that the “limited availability of Australian published literature affects the certainty of the evidence for the role of CAC scoring in the Australian setting”.

“This is a rapidly evolving area with emerging evidence, improved equipment limiting radiation exposure, and reducing out-of-pocket costs to consumers in the absence of public reimbursement.

“While historically there have been many challenges associated with clinical trials for the use of CAC scoring, the results of novel clinical trials currently underway will likely have an impact on the certainty of evidence for CAC scoring,” Jennings and colleagues wrote.

“We call for more research to define the role of CAC-guided risk assessment and management in the Australian population.”

Speaking with InSight+, Professor Jennings said that the new position statement was “a holding operation” while the 2012 guidelines are being updated, with release of the new document slated for October 2022.

Professor Jennings also noted that CAC scoring was not government subsidised nor was it easily accessible outside metropolitan centres.

“There are important equity issues given this is a test that the user pays for. And of course, it’s more widely available in inner city areas than rural and remote communities.

“Like a lot of new technologies, sometimes they can exaggerate inequity.”

Online first at the MJA

Perspective: Overdiagnosis of screen‐detected breast cancer

Milch et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51045 … FREE ACCESS for one week

Perspective: The future of brain banking in Australia: an integrated brain and body biolibrary

Rush and Sutherland; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51049 … FREE ACCESS for one week

more_vert

more_vert

Points 1 (to help differentiate moderate risk pts) & 2 (where risk factors are not captured within the NVDPA algorithm are well made, but as Prof Jennings highlights, there is little/no evidence that CACS actually helps management … and arguably hsCRP provides a similar level of risk assessment (as per improvement in ROC metrics)

Isolated case stories are often made (wee above) – but prospective RCTs clearly show that revascularisation does not improve the prognosis of most patients (except in the ACS setting). Sure, there are a handful where it may have helped, and a handful where the outcomes have been bad.

AMIs mostly occur from plaque rupture &/or intra-plaque haemorrhage at sites of mild-moderate stenosis, not at the tight lesions.

Worth remembering that Lifestyle & Medications treat all the artery, not just the bit that looks tighter.

Stents are a good treatment for angina.

Aspirin, b-blockers, ACEIs, statins…save lives.

I find using CTCA increasingly important in differenciating between those of a given (NVDPA) risk where no account is taken of family history, ethnicity or other ojective evidence of likely widespread atherosclerosis such as co-exising PVD with no previous diagnosis of CVD.

I have also found it useful for those low risk, who would like to pay for an investigation, significant reassurance when they receive a 0 or very low score.

As an example, I took on a new patient who had just jad BKA for PVD (mixed macro/micro vessel disease). I explained the likihood was that his CVD risk was higher given existing PVD. We decided to refer for CTCA, and the next time i saw him was post urgent placement of 3 x DUS for critical stenoses picked up on the scan.

An excellent result for him, and an anecdotal example of how high risk patients can be essentially fast tracked on the appearances. (Note, this compares with a similar patient who underwent a normal stress echo, was reassured, then experienced an MI only 2 weeks after that normal result).

As with everything, CTCA gives us another vital tool, however, I look forward to the day when these scans can be regarded as an important screening tool – not only that, but maybe there is a role for CTCA in detecting clinically significant cerbro-vascular disease?

As for most medical conditions, we need to consider the pathophysiology – what does it mean that patients have calcified vessel walls? In general, it means degenerative disease, which is seen more and more as the population ages.

We need to remember that the “open the artery” strategy, which started with thrombolysis and progressed to interventional cardiology, has been based on the pathophysiology of the occluding clot forming on an ulcerated plaque. This is quite different to calcified arterial wall, which is generally a sign of stability, not ulceration.

Modern interventional Cardiology does not meet the needs of the many older women with diffuse coronary disease in generally smaller vessels – in which stenting is not only less effective but also more hazardous.

We need more emphasis on accessible therapies that meet the needs of most patients.