AUSTRALIA’S top cancer control agencies have banded together to allay concerns about overdiagnosis of breast cancer, arguing that recent media commentary on the issue has downplayed the benefits of breast screening.

In a Perspective in the MJA, experts from Cancer Australia, Cancer Council Australia, Cancer Council NSW, the Cancer Institute NSW and South Australia’s Cancer Research Institute said the risks of cancer overdiagnosis needed to be viewed “in the context of screening benefits, such as reductions in the risk of breast cancer death”.

They warned of “harms associated with later diagnosis, including deaths from breast cancer”, which could become more common if the public discussion of overdiagnosis discouraged women from getting screened.

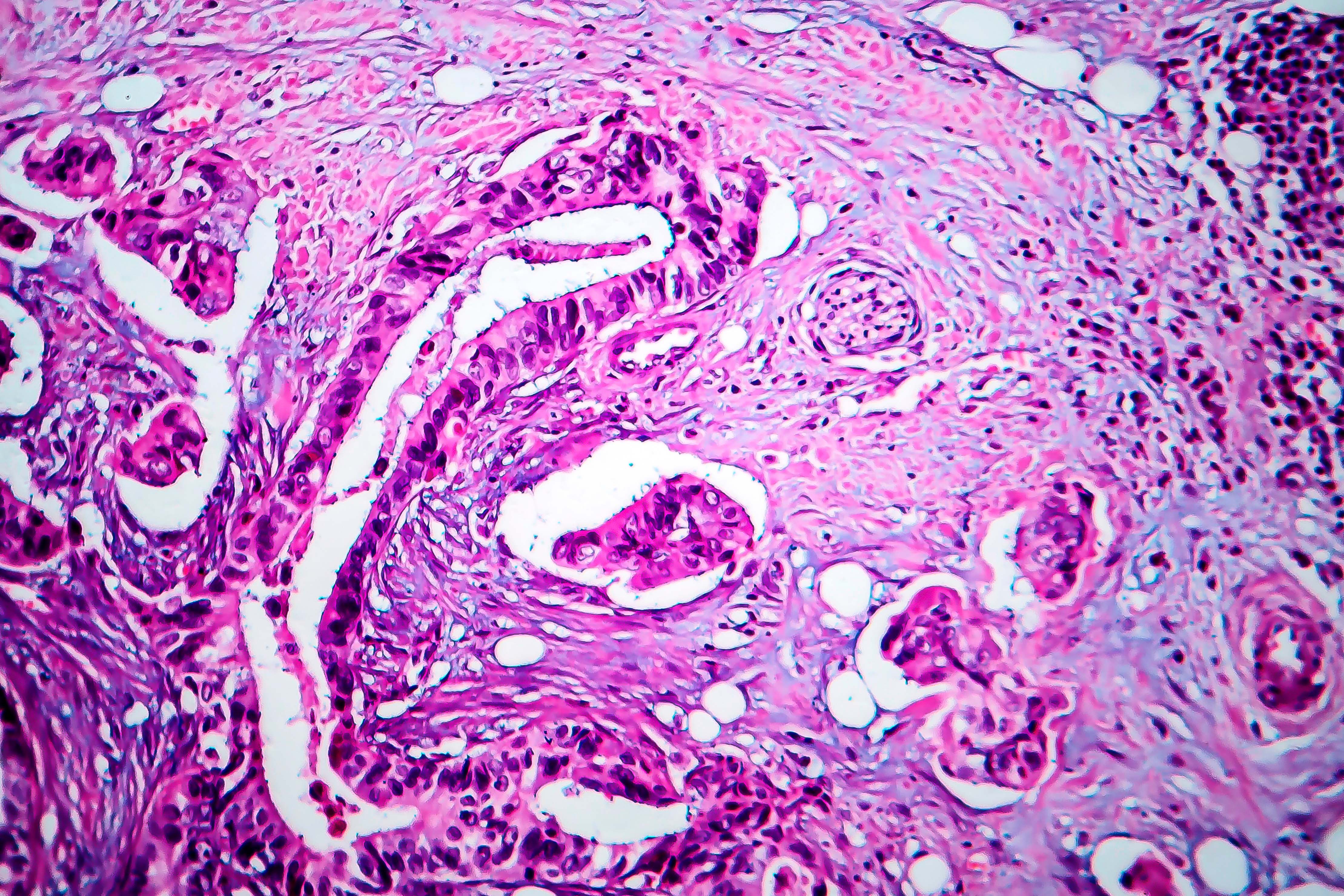

Overdiagnosis – defined as a histological verification of a screen-detected cancer that would not have gone on to cause death – was, to varying degrees, a reality of all screening programs, they said.

However, at the individual level, they added, it was impossible at diagnosis to tell which cancers would go on to cause morbidity or death if left untreated.

“The cancers that are overdiagnosed are indistinguishable from other cancers histologically,” they wrote. “As this is a post mortem classification, cancers can only be classified as overdiagnosed when another cause of death supervenes.”

A 2020 study in the MJA estimated the extent of overdiagnosis of a range of cancers, concluding that about 11 000 cancers in women and 18 000 in men may be overdiagnosed in Australia each year. Overdiagnosis rates were estimated at 22% for breast cancer (invasive cancer 13%) and 42% for prostate cancer.

However, the authors of the latest MJA article said care needed to be taken not to “conflate” formal screening programs such as BreastScreen with opportunistic approaches to early detection such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in prostate cancer.

“Major international reviews (here and here) have concluded, after a careful evaluation of the balance between benefits and harms, that there is a net benefit from inviting women to receive breast screening,” they wrote.

Dr Vivienne Milch, Medical Director of Cancer Australia, and lead author of the MJA article, told InSight+:

“We felt very strongly as a group of cancer control organisations that we needed to come together and draw out the issue of overdiagnosis in a measured and balanced way because much of the media commentary had understated the benefits of screening.

“We wanted to highlight those benefits, to support increased participation in breast cancer screening, which we know saves lives.”

Dr Milch said part of the problem was the complexity of the issue.

“There’s an academic debate about overdiagnosis, but that can’t guide the treatment of individuals because we don’t know which individual cases would progress and which would not progress if left untreated,” she said.

Potential harms of overdiagnosis included psychological stress and complications from interventions, Milch and colleagues wrote.

On the other hand, they cited Australian evidence that eight deaths would be prevented per 1000 women screened (range, 6–10). Furthermore, modelling suggested 70–90% of breast cancers detected by screening, if left untreated, would go on to be symptomatic and potentially lethal (here and here).

Milch and colleagues argued it was important to distinguish overdiagnosis from overtreatment, which could be mitigated by tailoring treatment for breast cancer according to evidence-based clinical management guidelines.

Professor Paul Glasziou, of the Institute for Evidence‐Based Healthcare at Bond University, was the lead author of the 2020 MJA study on overdiagnosis.

He told InSight+ he was pleased to see an explicit recognition from Australia’s cancer control organisations that overdiagnosis was a major issue with screening programs.

“It’s also good to see the discussion of overtreatment and the acknowledgment of research into alternative ways of managing different cancers.”

However, he argued that much more attention needed to be given to women’s values and experiences when evaluating the risk–benefit equation for breast cancer screening.

“Who decides on the balance of benefits and harms? We need to listen to women about it, either through a community jury or individual informed consent,” he said.

Professor Glasziou argued the overdiagnosis issues were similar for programs such as BreastScreen and opportunistic approaches to early cancer detection such as PSA testing.

“For both, some overdiagnosis is inevitable, but we need to reduce the proportion overdiagnosed and the consequences for those who are,” he said.

“The national breast cancer screening program was created in 1991, before we really understood the concept of overdiagnosis and the extent of it,” he added.

“If we were starting a breast cancer screening program today, it may well look quite different. For instance, we might assess peoples’ life expectancy before they were screened.”

Professor Alexandra Barratt of the University of Sydney, also a co-author of the 2020 MJA study, has previously written about the potential harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment from breast cancer screening, including anxiety, increased cardiovascular risk associated with radiotherapy, and the side effects and risks associated with hormone therapy.

“While I agree that overdiagnosis is a theoretical risk of all early detection efforts, it’s important to say that in practice, overdiagnosis and overtreatment aren’t features of all types of cancer screening; for example, cervical cancer screening and bowel cancer screening don’t cause cancer overdiagnosis,” she told InSight+.

“Cancer overdiagnosis is a problem with screening for breast, prostate, thyroid and lung cancer and policies to minimise it are needed when screening for these cancers.”

Since 2013, the UK has provided women with full and balanced information about breast cancer screening in the form of a decision aid when they are invited to breast screening, Professor Barratt said. Research suggests that such decision aids are associated with a small drop in women’s intention to be screened.

“Why is it still not happening here [in Australia]?” she asked.

“That would recognise that there is both potential benefit and potential harm from screening, and it would recognise women’s rights to autonomy and to make informed choices about their own health care if they want to.”

Professor Barratt suggested Cancer Australia’s estimate of eight deaths averted per 1000 women screened for breast cancer might be too high. An independent 2012 UK review of breast screening, based on data from randomised trials, estimated that four deaths would be averted per 1000 women screened, she noted.

However, Cancer Australia stood by its figures, saying they were based on more recent data than the UK review and reflected improvements in mammographic technology. Furthermore, they were based on Australian breast cancer rates and the Australian screening program.

Cancer Australia said women could receive detailed information about the potential benefits and harms of breast screening on the BreastScreen Australia website.

more_vert

more_vert

Breast screens are imperfect. I had a positive breast screen in 2013 confirmed by needle biopsy with a planned lumpectomy. A MRI prior to surgery, with a huge gap payment found a smaller suspected tumour so after discussion with my surgeon I elected for a mastectomy. Post surgery pathology found extensive DCIS missed by breast screen, high definition breast screen, two breast ultrasounds and the MRI. I did not trust any breast screening for the remaining breast and had an elective mastectomy post chemotherapy. Fortunately I have had no recurrence despite having triple neg breast cancer. What would the outcome have been if I had only had the lumpectomy? We need to get better at screening, not all breasts are the same, and at longer term monitoring after women have been treated for breast cancer, not just breast screening, but for cardiac complications, muscle loss, weight changes, mental health etc. Breast clinics and breast nurses appear to stop follow up after 12 months or so, then it seems to be up to your GP.

Unsurprisingly there’s no source given for the misleading claim that 8 lives are saved per 1000 women screened – because it simply can’t be true.

Australia currently has a 7 per 1000 incidence rate of breast cancer with 90% overall survival and a 0.1 per 1000 mortality rate. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-types/breast-cancer/breast-cancer-australia-statistics

Closer to the truth comes this publication from National Cancer Institute: ‘For mammography in women aged 50 to 59, for example, more than 1,300 women need to be screened to save one life.’

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/screening/research/what-screening-statistics-mean

Add to that the false-positive over-diagnosis and over-treatment of three women per one live saved as calcultated in the Lancet article https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61611-0/fulltext

Suddenly looks a lot less of a clear-cut to put all that money and effort into breast-cancer screening while not paying nurses decent wages and keeping public hospital beds and funding below what’s needed.

My concern about breast cancer screening is the harm – anxiety pain and worry as well as the burden of health anxiety – that is caused by multiple investigations for lumps that are found to be benign

The problem is the “cancers” found by screening are often those that go nowhere and the treatments for “cancer” are far from benign. I consider breast screening a controversial subject, the law and proper ethical standards say informed consent is essential, but it’s largely missing in women’s cancer screening. I’d say women are told what to do and counted off to reach targets for govt screening programs.

I think that approach is paternalistic and unacceptable. we should give women a balanced overview of the evidence and allow them to make an informed decision. Men are respected to make their own decision about prostate screening but because a govt program is in place for women’s screening, it becomes about targets. Sadly, we also, have powerful vested interests in women’s cancer screening and they have been allowed to run unchecked and unchallenged.

Prof Michael Baum (UK breast cancer surgeon) and our Robin Bell and Robert Burton are to be congratulated for their attempts to inform women (and doctors) of the risks v benefits of breast screening.

More women are getting to the evidence and choosing not to screen, that’s their right, their decision should be respected – women make decisions every day and accept responsibility for the outcome of those decisions.

50% of breast cancers are detected via breastscreen

50% are detected clinically by the patient and LMO

10% of breast cancers are missed at breastscreen because they are radioopaque ie; lobular cancers

Then there is DCIS = precancer and if not showing with microcalcification can be missed – which is where breast MRIs are the best way to detect

currently 1/7 lifetime risk of developing a breast cancer in Australia

we just need to keep monitoring breasts and educating our patients how to do it