THE National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has the potential to substantially improve services for people with complex disability needs who have previously missed out on supports.

The roll-out has not been without its problems, with consumers expressing concerns that the scheme is too complex and difficult to navigate, that the transition to the NDIS is confusing, and delays in access to decisions is frustrating. There is a lot of work to do to get the Scheme functioning well for Indigenous communities. The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) has acknowledged the implementation challenges for particular cohorts, including those with mental health concerns and cognitive impairment, Indigenous communities and those living in regional and remote locations.

Prison populations are also gaining attention as locations with a disproportionate number of people experiencing underlying disabilities.

Australian and international studies variously suggest that 30–60% of people in prison have a diagnosable acquired brain injury, and prison residents have more than double the rates of intellectual disability and mental health issues compared with mainstream communities.

The Australian Prisoner Health survey conducted in 2018 identified that 30% of prison entrants nationally report a past history of head injury with loss of consciousness and 40% of prison entrants (65% of women entrants) reported a previous diagnosis of a mental health condition.

Indigenous people currently comprise 28% of the Australian adult prison population and 53% of the detained youth justice population. A groundbreaking study of 99 young people in Western Australia youth detention, three-quarters of whom were Indigenous, found 89% had at least one domain of severe neurological impairment while 36% met full diagnostic criteria for foetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

Historically, mainstream adult mental health services have struggled to provide adequate support to those with behavioural issues arising from cognitive impairment and frequently co-occurring complex trauma. This has resulted in a significant cohort of people, often highly vulnerable, falling through service gaps. For too many of these people, the Justice sector has provided the major service response. This is clearly far from adequate. For Indigenous communities, incarceration continues to further disconnect people from culture, community and country without improving safety (here and here). It divests power from local communities to determine local solutions that strengthen community.

What is psychosocial disability?

While the NDIS places priority on a person’s functional capacity, it also requires a diagnostic underpinning outlining the permanence of any disability. The initial NDIS definition of “psychosocial disability” has described persons with a primary mental health condition who are experiencing significantly impaired daily functioning.

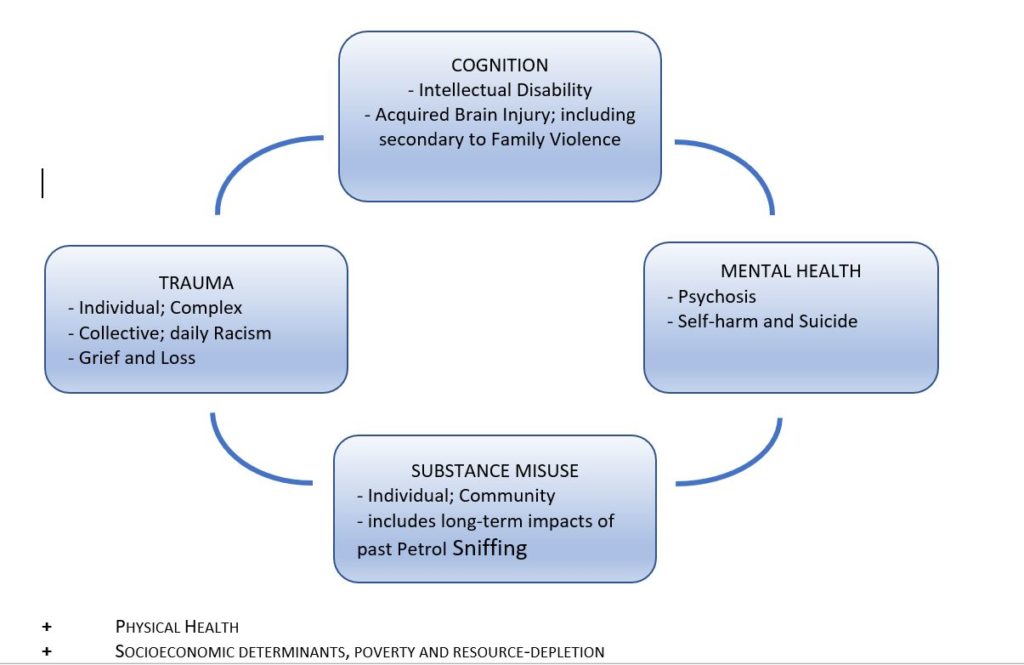

Within Indigenous communities, a better definition acknowledges the co-occurrence of four highly interconnected and mutually reinforcing domains that go beyond diagnostic boundaries and more accurately reflect lived experience (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The psychosocial complex: A transdiagnostic approach to psychosocial disability – acknowledging the strongly interrelated, mutually reinforcing influences on experiences of disability and daily functioning. Source: Krieg A. Psychosocial disability in remote Indigenous communities: a discussion paper. July 2020 (unpublished).

This trans-diagnostic model acknowledges the complex interplay between mental health concerns; complex traumatic experience; cognitive impairments, including acquired brain injury, intellectual disability and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder; and substance misuse in shaping a person’s daily functioning within the family and community context and their long term outlook. Daily functioning is also affected by physical health concerns and socio-environmental factors.

A redefinition in this way enables service providers to better tailor assessments and responses to fit Indigenous family experiences and ultimately work alongside Indigenous communities to advocate for more appropriate resources that directly respond to needs.

As voiced by Indigenous people across Australia, an understanding of traumatic experiences underpins any consideration of mental health concerns and psychosocial disability in Indigenous communities. Service models need to be founded on a rich understanding of the impacts of past and contemporary collective traumatic experiences endured by Indigenous peoples. Signs of collective trauma include elevated rates of physical and sexual abuse, family and community conflicts, leadership challenges, demoralisation, and widespread resource depletion. Responses are likely to be more effective when, rather than relying on individualistic approaches, collective worldviews that embrace local whole-of-community knowledge of truth telling and healing are also considered.

Recent work in Central Australia (Krieg A. Psychosocial disability in remote Indigenous communities: a discussion paper. July 2020 [unpublished]), funded through an NDIS Information, Linkages and Capacity Building grant, has involved mapping psychosocial disability support needs in several remote Indigenous communities. Multiple conversations with families, community members and service providers identified rates of mental health concerns and cognitive impairment substantially higher than mainstream Australia. Over 50% of roughly 180 eligible NDIS participants aged between 18 and 65 years in these communities had a primary psychosocial disability compared with an estimated 14% nationally in a mature NDIS program. Rates of intramuscular antipsychotic medication use suggest a psychosis prevalence 5-10 times higher than national averages.

Past petrol sniffing has had a major impact on a generation of people, both male and female, in some of these communities. Complex and collective trauma as a feature of daily life for many, not only affects an individual’s capacity to function well in their communities but also the capacity of families to care for those with disabilities. Remote communities are currently carrying the burden of risk arising from people with unsupported psychosocial disability needs – from physical and verbal aggression, property damage, sexualised behaviour and social disconnection to self-harm.

The needs of all Australian women with psychosocial disability currently remain largely hidden. Up to 40% of victims of family violence sustain a brain injury. The potentially high rates of acquired brain injury associated with family violence and the debilitating functional impacts of complex traumatic stress are yet to be evaluated.

Multi-agency mapping (Krieg, 2020 [unpublished]) also identified a significant cohort (about 20%) of psychosocial participants in the NDIS, mostly with acquired brain injury, with known confirmed histories of sexually harmful behaviour. International studies variously suggest that 40–57% of people with an acquired brain injury report hypo-sexuality, while inappropriate sexual behaviour is reported in 7–15% of cases.

Therapeutic responses, such as environmental change, psycho-education and specific behavioural techniques, can be effective in reducing challenging behaviour, including sexualised behaviour, aggression or violence, justice issues and social disconnection, in participants with and acquired brain injury. Basic environmental measures such as supported accommodation increase monitoring and reduce exposure to potential victims. The NDIS can provide targeted supports through well designed positive behaviour support plans to respond directly to a range of challenging behaviours and support more appropriate expressions of behaviour.

“Let the market decide”

There are big questions about the suitability of a market-driven model to respond to psychosocial disability in Indigenous communities, particularly in regional and remote areas. Detailed data from the NDIS identifies that smaller markets have fewer choices, low plan utilisation and fewer providers.

In small markets, a competitive model works against service integration, information sharing and shared accountability.

Currently, the major accountability mechanism for service quality and integrity within the NDIS is the NDIS participant and their family. In many remote communities, where psychosocial supports have been largely absent, communities do not yet know what good services could look like and are not well positioned to advocate for their own services or to hold service providers to account. Disability participants and families are left exposed to the risks of a culture of low expectations, exploitative practices and poor quality services.

The NDIS does acknowledge that different funding models may need to be considered, including, as a last resort, direct commissioning.

The majority of Indigenous people experiencing disability have complex needs. Good care requires good collaboration – including a willingness to share information and clarity around respective roles – across multiple sectors, state and federal government agencies, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations, GPs and non-government organisations, spanning health, disability, justice and other service sectors. While this may sound daunting, attempting to negotiate all these sectors is the daily experience for many Indigenous families. Processes to create the systems of care needed are not yet in place and cannot be funded from within individual NDIS plans. Investment now in multi-agency service coordination and planning with community involvement every step of the way will reap substantial benefits for Indigenous communities over the longer term.

Primary health care services and the NDIS also need a strong interface. Particularly in many regional and remote areas, health services provide the main infrastructure and resources for people and families affected by disability. However, from what I have observed in multiple settings, some health providers are choosing, understandably, to have minimal engagement in NDIS-related activity unless additional supports are in place to do so. Currently there are no MBS items linked to NDIS-related activity. Creating specific NDIS-linked Medicare items – to assist with evidence gathering, shared care, planning and coordination – could improve the effectiveness and timeliness of NDIS service delivery, while compensating health care providers for the additional workload associated with NDIS-related work.

NDIS solutions intersect with other contemporary priorities for reducing Indigenous incarceration rates: reforming discriminatory policing practices, raising the age of criminal responsibility to 14 years, introducing problem-solving courts based on therapeutic rather than punitive approaches to sentencing, expanding restorative justice practices within the justice sector and wider community, and investing in community-based solutions, examples of which are seen in Australia’s approaches to justice reinvestment.

Many correctional jurisdictions, adult and juvenile, in Australia are beginning to explore ways to work more closely with the NDIS to build disability pathways for offenders out of the justice system.

A child at court is a child at risk – as is any young person attending youth or adult court. All young people deserve a comprehensive assessment for cognitive impairment and other psychosocial disability before sentencing and ideally before being remanded in custody. Health–justice partnerships, engaging health and disability services with court processes, are overdue to ensure young people with psychosocial disabilities are identified early and offered appropriate community-based supports rather than imprisonment.

Such partnerships have wider implications beyond incarceration. By successfully managing the needs of those affected by the justice system, we will create systems of care that support many of the most vulnerable people in other settings, such as those engaged with child protection agencies.

While the issues are complex, it is entirely possible to achieve excellent outcomes when service responses within communities are well planned, coordinated and well implemented.

The message for working in complex systems is simple: “It’s all about relationships.”

Dr Anthea Krieg is a medical practitioner who has worked over many years with Aboriginal communities around Australia. She has extensive experience in mental health services, including acute and community psychiatry, trauma and abuse, cognitive impairment and a particular clinical and research interest in Aboriginal incarceration. She can be found on Twitter at @GoodKidMadSystm.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

This is an excellent summary of a very complex challenge facing our most disadvantaged people. I’m often disappointed by the over simplification of the multiple factors that contribute to some of our most heartbreaking truths as a nation. Unfortunately there are no simple solutions but understanding the problem will help us to move one step closer to providing the care that is needed.

Thank you for this article.