I KNEW I was gay in high school. There was no confusion or struggle internally, I just was. The pain came from trying to work out what to do about it. Unfortunately, I was exposed to many complex and conflicting ideas about what being gay meant for me and my life.

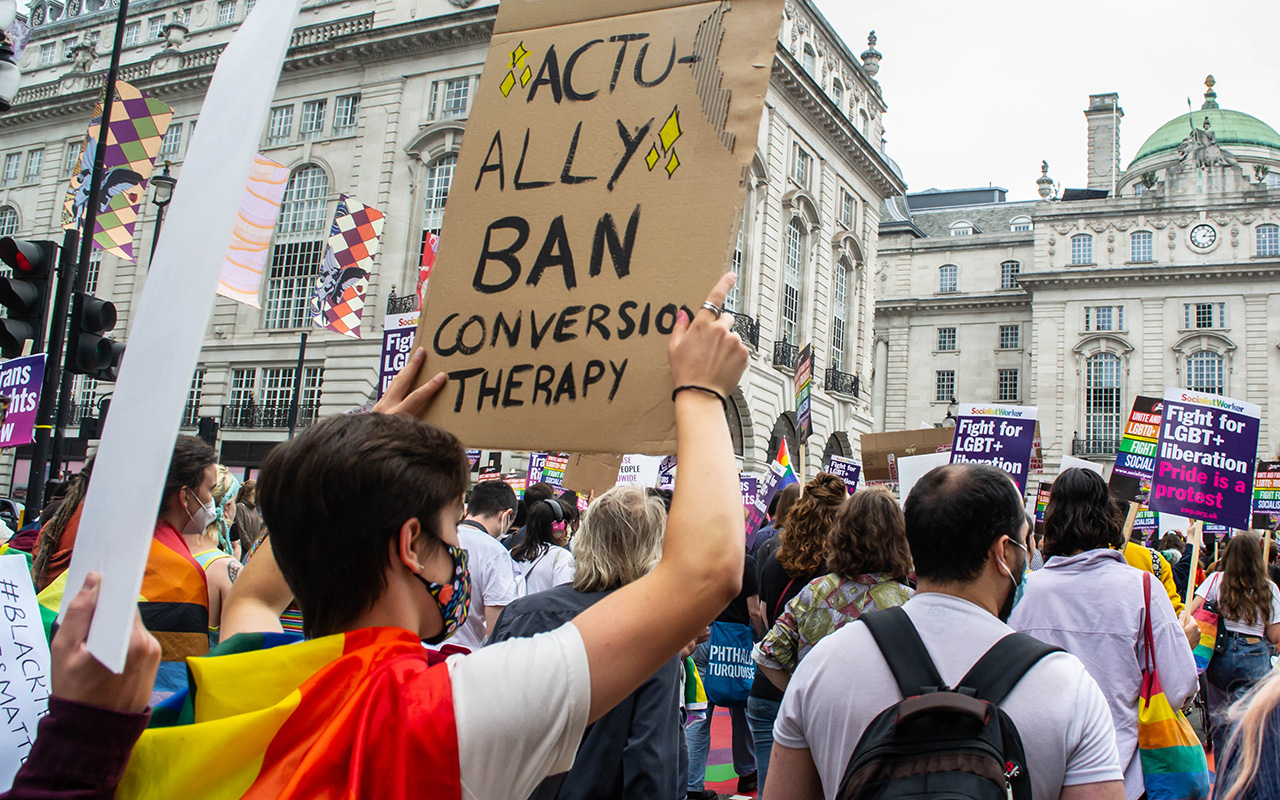

“Conversion practices” is a broad term referring to any formal or informal intervention or attempts to change or suppress someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity (here, and here). It is a problem that remains endemic in Australia (here, here, and here). “Conversion practices” has more recently replaced the term “conversion therapy” to better reflect the range of interventions that can be involved.

The first person I came out to was my best friend in 2009, who told me that if I “chose” to be gay, I would be fundamentally unlovable and would burn in hell forever. They told me they loved me and were telling me this because they loved me, and I believed them. Suffice to say I did not come out to anyone else for years. When I did it was to a pastor who encouraged me to date people of the opposite sex if I “could”. Long after that, I told the person I eventually married as I felt they surely had a right to know.

The year 2017 was the most difficult and damaging year of my life. As I tried to leave this community for a number of reasons, attempts to suppress, convert or “cure” me intensified as more people found out about me. That was also when these attempts started to actively involve other health care professionals. Specifically, a general practitioner and a psychologist.

In counselling and therapy sessions, I was told by these health professionals that it would be better for me to be dead than divorced. I was told that regardless of what I did with my life, it would not matter. Whatever care and compassion I showed people, how much good I tried to do in the world, no matter who I loved or how, none of it would matter. It wouldn’t count the way it did for other people. I was told that being gay would invalidate my entire life and that nothing could ever make up for that. I was told I would lose my family and friends, and have a lonely, loveless, condemned and worthless life. I was exposed, degraded and humiliated in front of people. I was given resources including a book by a celibate “same-sex attracted” pastor as an instruction for how I should live.

During that time in 2017, I was working in hospitals completing my first year of general practice training. At that early stage in my career, and in the midst of manipulative behaviour under the guise of having my best interests at heart, I was not able to recognise how deeply unethical and damaging the treatment I received from these people really was. For quite some time, I was also prevented from accessing appropriate, professional and competent health care. I am infinitely grateful for the people I met when I did, and that it was not too late for me. Brilliant doctors and psychologists eventually protected me, and gave me the space, time and therapy I needed to begin to heal from prolonged traumas.

In hindsight, I lived in and around a community with a culture of conversion practices, spiritual abuse, and coercive control for almost 10 years. However, being subjected to these practices by health care professionals had a particularly profound impact on me as a doctor. I had to reconcile having been harmed by people within the system I am a part of, by colleagues. These were people I assumed I could trust, who were taught to first, do no harm. To do good. To treat people fairly and equitably. To uphold and protect individual autonomy.

My experience showed me the power that we have as doctors by experiencing the abuse of that power. I perhaps naively assumed that an individual’s professional ethical obligations would outweigh their personal beliefs in this context. Even if this was challenging for them, I trusted that the escalating pain I was in would make it clear that their approach was wrong. It never did.

Being a responsible doctor involves lifelong learning, reflection, ethical conduct, and practising evidence-based medicine. There is overwhelming evidence of the harms inflicted by conversion practices, and that they do not work. Both the Australian Medical Association and the Australian Psychological Society have released position statements denouncing conversion practices.

Many people reading this will be surprised to know conversion practices still happen in Australia. Although the methods and rhetoric have changed over time, they remain prevalent. Conversion practices in contemporary Australia are deceptive and insidious. They are often conducted by people and communities who claim to be “welcoming” and “loving” to gender and sexually diverse people, but in fact treat homosexuality and gender dysphoria like any other “sinful temptation” to be fought, potentially for your entire life. This polite duplicitousness causes immeasurable confusion, shame and complex trauma for so many people, and takes the lives of many others.

I also know many people reading this article may find it challenging or uncomfortable because of their own personal beliefs. If this is you, instead of fighting any discomfort you may have, be curious about it. Ask yourself why you feel uncomfortable. Difference is nothing to be afraid of, but ignorance is. It is ignorance that hurts people, not difference. At some point you were taught what to think and feel about these issues, as we all were. Our knowledge and opinions are learned over time. Although continuing professional development can feel like the bane of one’s existence when busy and overworked, ongoing learning and self-reflection really is an integral part of being a good doctor. Growth, both personally and professionally, always involves change. It is important to challenge and refine your views and practices over time. It is okay to change your mind. In fact, when the evidence is clear, it can be unwise and harmful not to.

I was originally commissioned to write this article after delivering a speech at the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Fellowship Ceremony in October 2021, where I shared part of my story publicly for the first time. To be honest, I was fairly convinced I would either get in trouble for talking about it, or people wouldn’t care. It is not easy to talk or write about complex trauma, and it hadn’t been possible for me for a long time. It is harder still when you assume you have a hostile audience based on past experience. However, the reception and feedback was incredible. Having colleagues, strangers, family and friends show their support, come up and thank me or discuss their own experiences or those of loved ones was overwhelming. I didn’t expect it at all, so I had no concept of how positive and helpful it could have been for me personally. It took the first ten to 15 people at least for me to start to trust that people weren’t lining up to have a go at me. After that, I felt something physically start to shift in me. A constant hum of threat, a baseline fight–flight energy that I felt and sometimes still feel in medical circles started to settle. I left that event feeling, for the first time, truly seen, valued and safe in my professional community.

Although I have had some truly awful experiences in my life, they have overall been completely outweighed by the good. It has taken a long time and a lot of work, but I now know that I am truly valued and loved. I have great friends, family, colleagues and a fantastic partner. So, finally, to anyone reading this who is in a similar position to where I was: it may not feel like it, but you are and will be okay. It may not be the people you hope or expect, but there are so many people who do and will love, accept and value you. There are people who will help you if and when you are no longer able to help yourself. Do not give up looking for them.

Dr S Whyte is a general practitioner.

This article was originally published by the Medical Journal of Australia. Read the original article here.

If this article has raised issues for you please reach out to any of the following resources:

DRS4DRS: 1300 374 377

- NSW and ACT … 02 9437 6552

- Victoria … 03 9280 8712

- Tasmania … 1800 991 997

- Queensland … 07 3833 4352

- WA … 08 9321 3098

- SA and NT … 08 8366 0250

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, there are people here to help. Please seek out help from one of the below contacts:

- Lifeline| 13 11 14| 24-hour Australian crisis counselling service

- Suicide Call Back Service| 1300 659 467 | 24-hour Australian counselling service

- beyondblue| 1300 22 4636 | 24-hour phone support and online chat service and links to resources and apps

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert