ANOTHER family begins the terrible journey of coming to terms with the death by suicide of one of their bright young people. Another group of medicos is facing the trauma caused by the loss of a colleague. Another article has been written by another doctor who is furious, frustrated and forlorn at the lack of true change in medical culture.

In the words and wisdom of Dr Martin Luther King Jr, “Since we know that the system will not change the rules, we are going to have to change the system”.

The media is littered with reports on medical doctors, at all stages of training, committing suicide. This is not ground-breaking news. The first article listed in the PubMed database on physician suicide was published in 1922. Then director of the Bureau of Public Health Education, Dr Hubbard recognised that lives could be spared “if given adequate consideration”.

Yet 100 years later, the problem continues to be swept under the rug or given lip service by leaders in hospitals and in medical education. It’s time to flip the script. Instead of asking our patients, we need to ask ourselves and our colleagues, how can we stop yet another untimely death?

The facts are clear:

- female physicians commit suicide at 227% the rate of the general population;

- male physicians commit suicide at 141% the rate of the general population;

- one in four junior doctors report suicidal ideation (Table 15, page 31)

- one in two junior doctors experience moderate to high distress; and

- junior doctors working long hours double their risk of suicidal ideation.

None of these facts are new, nor have they changed.

While the role of fatigue on suicidal ideation has been well documented in the literature, doctors in training continue to report unrostered, unpaid, unsafe working hours across Australia (here, here and here). Several class actions have been launched not only to address this situation but also to ensure penalties are placed against the health services that allow these situations to continue. For years, the Australian Medical Association has urged workplaces to consider the impact of fatigue on the wellbeing of its medical staff. For years, this plea has gone unanswered.

The complex professional and personal demands placed upon female physicians have been thought to be a driving factor in increasing their risk of burnout, depression and suicide. Studies have found that medical mothers not only believed motherhood would slow career advancement but were also more likely to reduce working hours to avoid work–family conflicts.

The limitations to career progression are compounded by the reduced ability to partake and publish research for female physicians. This is supported by the research by Fridner and colleagues that found a negative impact between high rates of exhaustion among female physicians and the number of published articles. With the pressure to perform professionally and personally, many have postulated that this undue unequal pressure on female physicians has led to the significant suicide rates.

The final fact that must be acknowledged is that doctors are not seeking help for their mental health for fear of professional repercussions and social stigma (here and here). R U Ok, Vital Signs, and We are medicine and we are human are all campaigns that have attempted to address the stigma of mental illness. Ultimately, however, the stigma has prevailed.

We are afraid that by seeking help, our careers will end prematurely. We are afraid that by seeking help, our colleagues will doubt our clinical acumen (here, and here). We are afraid that by seeking help, we will not be allowed to practise medicine. These fears become all-consuming and outweigh the fear of losing our own lives and even the fear of never seeing our loved ones again.

How do we stop yet another preventable death and the trauma that follows for all their loved ones? The truth is we do not have the answers yet but they are within reach.

Recently the South Australian Government amended their Health Care Governance Act to make workforce psychosocial wellbeing a clear responsibility of hospital directors. This is an excellent example of meaningful change to address a critical driving factor in physician suicide. Senior hospital management, government, and the Medical Board need to recognise their duty in improving and supporting the safety of our colleagues.

The Australian Medical Association Queensland Council of Doctors-in-Training proposes a Queensland Health and Hospital Health Services symposium to hear from experts in the field and to compile a list of actionable items to instigate changes in our medical culture. By bringing senior leaders of the medical profession together and committing to these changes, we hope we can protect our colleagues from another death.

Last Thursday the AMA Council of Doctors in Training and the Australian Medical Students’ Association released a traffic lights flyer which “lists all support services available and recommends which to access depending on the level of stress experienced”.

The status quo is literally killing us. Change was needed years ago, refusing to work towards that change now is inexcusable. While we continue to advocate for systemic changes that we all know are needed, we ask that regardless of your career stage you consider how we can better support each other. Asking “R U Ok” is a good first step, but now is the time for action so we are all able to honestly answer “Yes”.

If this article has highlighted difficulties that you are experiencing, please contact your state Doctors’ Health Advisory Service helpline for 24-hour confidential support and advice. In Queensland, you can find further information at www.dhasq.org.au with confidential support and advice through our helpline (07) 3833 4352, while other states’ phone numbers can be found at www.adhn.org.au

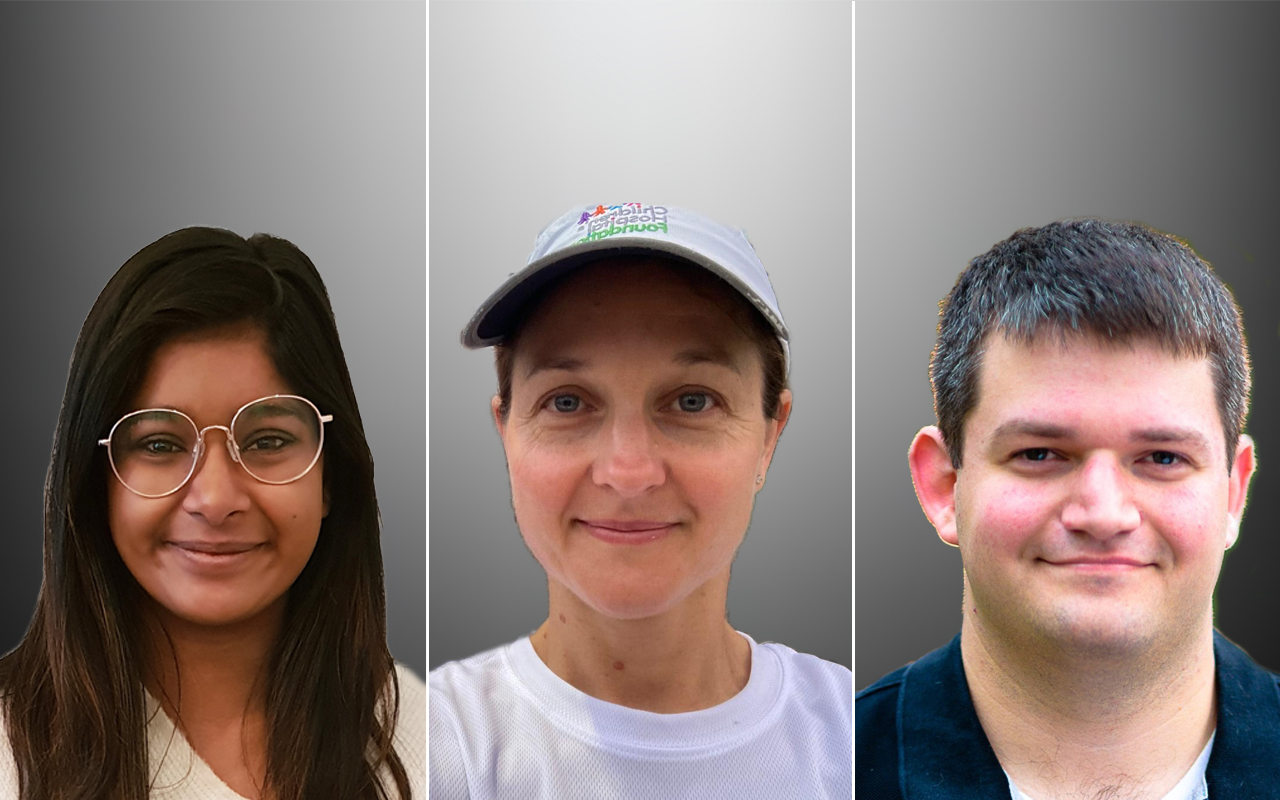

Dr Natasha Abeysekera is an executive member of the Australian Medical Association (AMA) Queensland Committee of Doctors in Training. She is currently working as a principal house officer in General Surgery at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital.

Dr Rachele Quested is an executive member of the AMA Queensland Committee of Doctors in Training. She is currently working as a registrar in Radiology at the Princess Alexandra Hospital.

Dr Robert Nayer is an executive member of the AMA Queensland Committee of Doctors in Training. He is currently working as a registrar in Emergency Medicine at the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service.

If this article has raised issues for you please reach out to any of the following resources:

DRS4DRS: 1300 374 377

- NSW and ACT … 02 9437 6552

- Victoria … 03 9280 8712

- Tasmania … 1800 991 997

- Queensland … 07 3833 4352

- WA … 08 9321 3098

- SA and NT … 08 8366 0250

Medical benevolence funds

AMA Peer Support Line … 1300 853 338 or 1800 991 997

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, there are people here to help. Please seek out help from one of the below contacts:

- Lifeline| 13 11 14 | 24-hour Australian crisis counselling service

- Suicide Call Back Service| 1300 659 467 | 24-hour Australian counselling service

- Beyondblue| 1300 22 4636 | 24-hour phone support and online chat service and links to resources and apps

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

“My understanding is that if there is evidence of mental health issues AHPRA needs to be notified and the possibility of de registration is a possibility. ”

This not accurate. There are many doctors, nurses, physios, and other AHPRA registered practitioners who practice good, safe medicine and have mental health issues.

“The threshold for mandatory reporting is having a ‘reasonable belief’ that a treating healthcare practitioner is putting patients or the public at substantial risk of harm”

If you or anyone you know is having difficulties – please use the flyer or contact any of the above services.

The Elephant in the room is AHPRA.

My understanding is that if there is evidence of mental health issues AHPRA needs to be notified and the possibility of de registration is a possibility. My understanding also is that if you seek help from another GP , that GP is required to notify AHPRA. If you are living in Western Australia the above is not relevant. If you live anywhere else in Australia you are not safely eligible for the help that your patients are eligible for , for fear AHPRA will be notified.

If this is incorrect please advise , as this is information we received a few years ago after Australia ( except Western Australia) agreed to follow a decision made in Queensland.

A well intentioned article, but I must point out that “commit suicide” is not the correct terminology. Die(d) by suicide is less stigmatising.