PREVENTING a state or territory locking down for a single week can be worth between $500 million and $4 billion dollars. The potential learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic hold an intellectual capital valued in the tens of billions of dollars.

So many of the factors that challenged our response in 2020 and 2021 were identified again and again over the past 20 years as described in our recent summary of 14 after-action reviews (AARs) of Australian outbreaks. Challenges identified repeatedly include communication, surge capacity, incident control systems, information management and sharing, clarification of roles, decision support and risk assessment, and need for exercises. To respond to the ongoing pandemic, and to prepare for the next pandemic, we need to build infrastructure to harvest and implement lessons from AARs and intra-action reviews (IARs) from this pandemic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been urging countries to commence IARs of our current pandemic response since June of 2020. There have been 105 IARs of COVID-19 responses conducted at the national level and reported to the WHO. Within Australia’s WHO Western Pacific region, eight countries have conducted IARs, including Mongolia, New Zealand, Vietnam, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Cambodia. South Africa, which has had multiple severe waves of COVID-19, has conducted one 3-day IAR and three full-day or 2-day IARs.

Australia has not conducted reviews within the broader WHO framework, but it has conducted important reviews of pandemic response, such as the National Review of Contact Tracing and the Quarantine Hotel Review.

At peak pandemic response, Australia had the most pandemic ready workforce it has ever had. The workforce had been increased, perhaps fourfold, although this has not been systematically documented. Similar to wartime field promotions, many staff have been catapulted into senior positions and gained a career’s worth of public health experience in less than 2 years. We are at the peak of our performance and must capture insights into what has gone well, what can be improved, and what can be done to mitigate the next pandemic.

Unfortunately, most of those who could distil these learnings are still working around the clock on the ongoing response.

So many of the lessons of the 2009 influenza pandemic were lost in the 10 years leading up to this pandemic. Lost insights into contact tracing workflows and systems, stockpile requirements and management, border controls, communication with the public and across agencies, surging human resources and ongoing training needs were unable to be leveraged efficiently from the last pandemic. Many of the recommendations of the 2009 influenza pandemic review were not implemented.

We can begin now by responding to the WHO’s recommendations to initiate IARs of our pandemic response. There are several guides to assist public health agencies to undertake these reviews. This should be conceived as a national infrastructure project rather than merely a research project.

Before describing the national infrastructure project, there are actions we can take immediately. We need to immediately encourage every public health practitioner and every team to capture and preserve their breakthrough processes, insights and protocols.

An agenda item on weekly meetings could be “Notes to file for the next pandemic” to collate issues for IARs or AARs. Many of us have been compiling such notes since the first weeks of the pandemic but this practice needs to be broadened. Every pandemic responder needs to have a document on their desktop to capture insights to share in pandemic reviews. Such a long and protracted response will rely on the recollection and documentation of responses of thousands of participants at multiple government levels and sites.

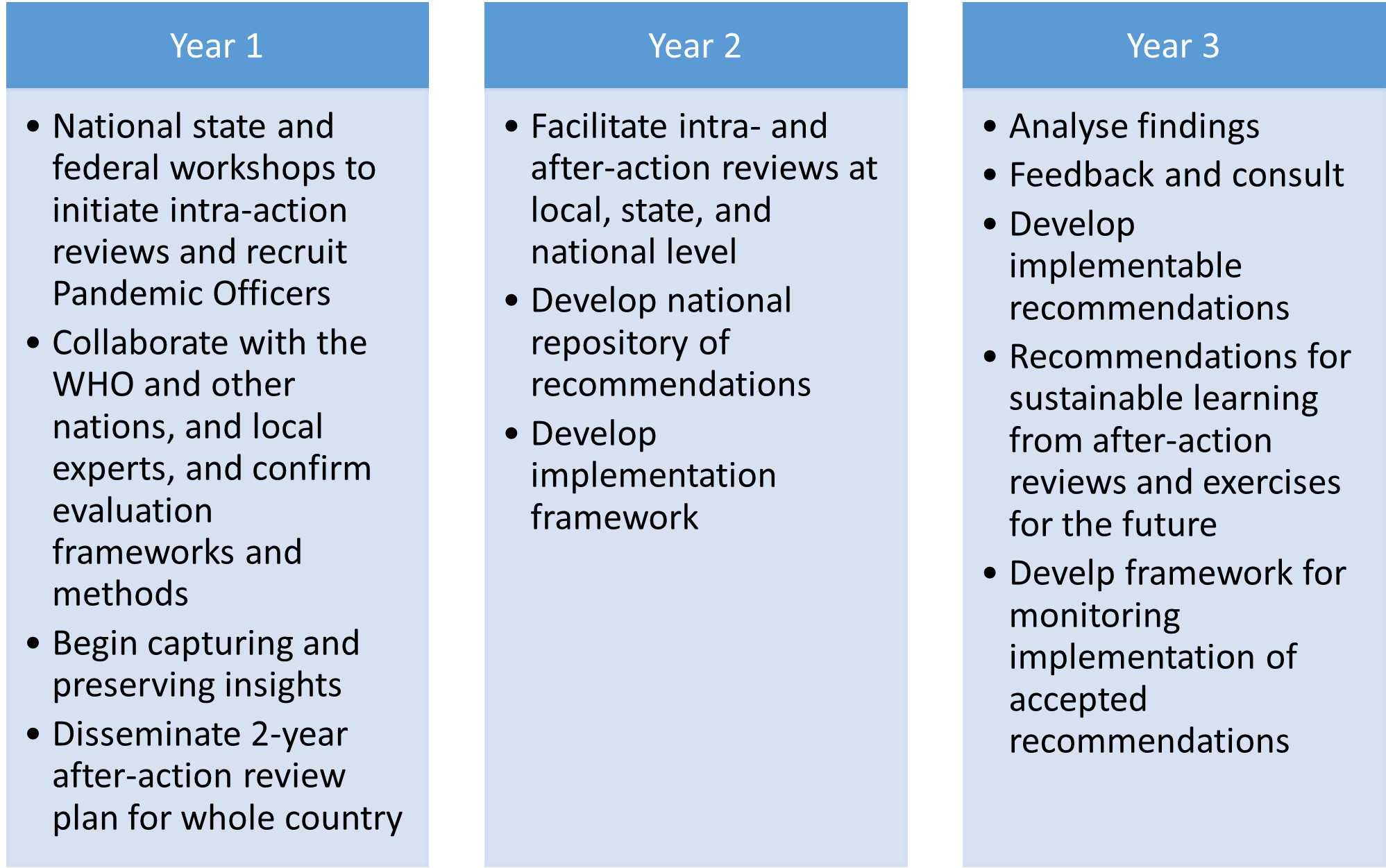

Comprehensive AARs across the breadth of WHO pandemic response pillars will require the sort of commitment and resources that go into planning a major infrastructure project. Harvesting the learnings will consume 2 to 3 years and implementing them could take the best part of a decade.

To support this program, a model described as the “Pandemic Officers Program” is proposed – a workforce of early, mid and late career professionals to support the IAR and AAR process and create the scaffolding for implementation of recommendations.

While drawn primarily from public health disciplines, the scholars would be drawn broadly from the fields of epidemiology, laboratory science, law, ethics, IT, Indigenous and CALD health, evaluation, ethnography, and group facilitation skills. It will require a serious commitment of time and resources to engage the approximately 50 units of public health pandemic response in this country, including the federal health department, the eight state and territory health departments, and the approximately 40 regional public health units that were the frontline of response.

Some have argued that a Royal Commission into Australia’s pandemic response should be conducted. Royal Commissions can cost several hundred millions of dollars. As has been suggested from Australian bushfire AARs, a national AAR process that transparently integrates shared learnings into practice may be superior to quasi-judicial commissions of inquiry. Such inquiries often limit root cause analysis and discovery of learnings because of their adversarial nature. Witnesses examined in such enquiries are briefed by legal counsel on strategy and approach to questioning. There is not an open collaborative approach to documenting learnings for the future. The Special Commission of Inquiry into the Ruby Princess is an example of such a process. While not without value, it was run by a lawyer rather than a public health expert, with an adversarial “examination” of witnesses. Key public health questions and insights were missed by this inquiry.

The Pandemic Officers Program would be much less expensive than a Royal Commission and would arguably make a stronger contribution to the future using the same processes adopted by other countries for WHO reviews. The initial workforce and program planning estimate requires approximately 55 professional staff embedded across local, state and federal health departments at a cost of $30 million over 3 years.

To put this cost estimate in perspective, it is equivalent to only 9 days of PCR testing during the peak of the Delta pandemic and need to offset less than one day of lockdown in a future pandemic to break even economically.

Ensuring that government uses the learnings to transform public health practice will be the greatest challenge. Our research has shown that just identifying opportunities for improvement and knowing “what to do differently next time” doesn’t necessarily lead to change. Many of the recommendations from AARs of the 2009 pandemic were not acted upon.

The recognition that learnings from AARs of bushfire responses were not acted on over years triggered the development of a national repository of recommendations to help ensure their implementation. The database provides both a resource for future response and, potentially, an accountability framework. A repository of public health recommendations is incorporated into the US Homeland Security Digital Library.

Spurred on by the pandemic, public health agencies around the world are expanding their “pandemic learning infrastructure”. It is seen as an economic investment in mitigating the next pandemic — which could be later this year. Clearly, it is worth the investment.

Dr Craig Dalton is a public health physician and Conjoint Associate Professor in the School of Medical Practice and Population Health at the University of Newcastle.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Good intentions pave the road to ….

Another opportunity for groupthink biases I’m afraid. Like so many of our ‘independent’ organisations and reviews – established with answers already in mind then use selected evidence to ‘justify’ positions. TGA, ATAGI, AHPRA, covid evidence taskforce, MBS review, etc anybody? Draft positions for public comment rarely change for the final.

I couldn’t agree more about the need to learn from the past.

The ability of the individual state in our federation to trial different measures has shown us what works and what doesn’t work.

We do need a national CDC that works. (The American model apparently did not.)

I have heard we left our ideology at the door when we entered this pandemic.

Clearly the old ideology was not fit for purpose.

Really excellent recommendation from Craig Dalton and very well explained and justified.

An additional consideration is how will we get better coordination and communication between the individual jurisdictions and also between them as a group and the Commonwealth? There have been some important templates of guidance for COVID responses developed at a national level, such as the work of CDNA and PHLN, but also there has been a lot of duplication of effort when States/Territories each scrambled to make policy and guidelines on the same issues independently. Is it best to have each State/Territory mostly do its own thing, write its own plans and guidelines and implement without a “national” focus? It could be argued that the independent actions of the States and Territories at different time intervals in relation to their own borders was a big part of keeping COVID from becoming a pan-Australian pandemic during 2020 and 2021. Nevertheless, stronger Commonwealth leadership at a public health level (rather than political), with more resources for guidelines and response support and for national coordination of real-time data collection and analysis, could have freed up public health staff and clinicians at the coal face in the jurisdictions to focus on implementation of COVID responses, rather than having to continually cobble together separate guidance and policies on the fly. This is why the call for an Australian CDC remains as relevant as ever.