FRONTLINE clinicians are critical to effecting health care improvements. Their experience and frustrations with current systems help them identify problems and solutions. Equally important, clinicians must play a key role in leading any implementation process to ensure improvements are sustained (here and here). Postgraduate programs are readily available for clinicians to acquire change management and leadership skills including the Health LEADS framework for leadership, implementation science and negotiation skills.

Yet despite exhibiting passion for quality improvement and attending workshops and training programs, many clinicians feel unable to effect change because of entrenched barriers within health systems. It may be possible to overcome these “roadblocks” by understanding the power of “clinician levers”. Clinician levers are arguments and mechanisms that clinicians can use to keep partners engaged, reach agreements and effect change. They represent the informal power that frontline clinicians wield, which arises from their accepted patient advocate role. However, these levers, although powerful, may be invisible to clinicians. This contrasts with management levers that are made available to managers and clinical managers, arising from their formal positions.

In our experience, effective levers for clinicians to use in their negotiations with stakeholders include those related to patient safety and quality, disparity in access and outcomes, reference to organisational and government strategic plans, staff welfare and rights, accreditation standards, industrial agreements, membership in staff societies and peak clinical bodies, escalation through line management, and connections with patient advocacy groups, politicians, government agencies and media. The more complex a problem is, the greater the number and more diverse the set of clinician levers need to be.

To illustrate, we relate a real-life complex example in which a telechemotherapy model was implemented to enhance rural access to chemotherapy closer to home across a large geographical area covering five health services in North Queensland, Australia.

When we as a group of clinicians conceptualised and developed our telechemotherapy model based on telehealth literature, research findings of our telehealth models, and consensus among multidisciplinary professionals (here and here), some of our managers and colleagues were resistant to the concept despite multiple efforts at discussions. They had many understandable concerns about the model, the sum of which, for them, meant it was “all too hard”.

Our initial clinician levers included advocacy for patient welfare — “every day we delay implementing this model, more rural patients with limited survival times are forced to travel and suffer more social and financial distress”. We reminded them that “enhancing access to care closer to home” had been listed as a priority in the government’s strategic plans. We also made connections to inform and educate cancer consumer and rural clinical networks in our state which could use advocacy levers at department of health level. During the concept phase and early implementation, when sites were not adhering to agreed timelines, we used escalation to their managers and involvement of consumer advocacy bodies in those communities as our clinician levers. Our confidence at negotiation grew over the years because of clinician levers.

To give the clinician levers even more power, we collected model-related data and presented them at statewide and national forums. The data enhanced the credibility of the initiative. Ongoing publication of key outcome measures, combined with ongoing application of the clinician levers, ultimately enabled us to convince the regional health services, metropolitan colleagues and state government to adopt these models as routine business.

How then can a passionate clinician with a good idea, make use of clinician levers? Our observation is that clinician levers are most effective when the issue resonates with colleagues and managers, the solution to the issue is feasible, and the implementation plan has the support of key stakeholders. Even when these necessary steps to implement an idea are in place, roadblocks may still arise. Therefore, clinician levers need to be identified and applied from the outset, so that the intrinsic altruism of other clinicians and managers can be sustained throughout the process of change.

In conclusion, clinicians who are passionate about improving the system need to fine tune all the aspects of the Health LEADS attributes to gain the trust of their colleagues. When implementation science frameworks are followed, we will have automatically established that the problem and its solution have value, and we will have brought in the many stakeholders who are needed to support our venture. Negotiation skills ensure that all stakeholders’ concerns are addressed without overly diluting the intent. At the outset, it is important to think about what clinician levers to apply when negotiations fail or stall so that we can effectively keep others engaged and maintain momentum to effect change; empowering the clinicians and sharing the vision of better health for all.

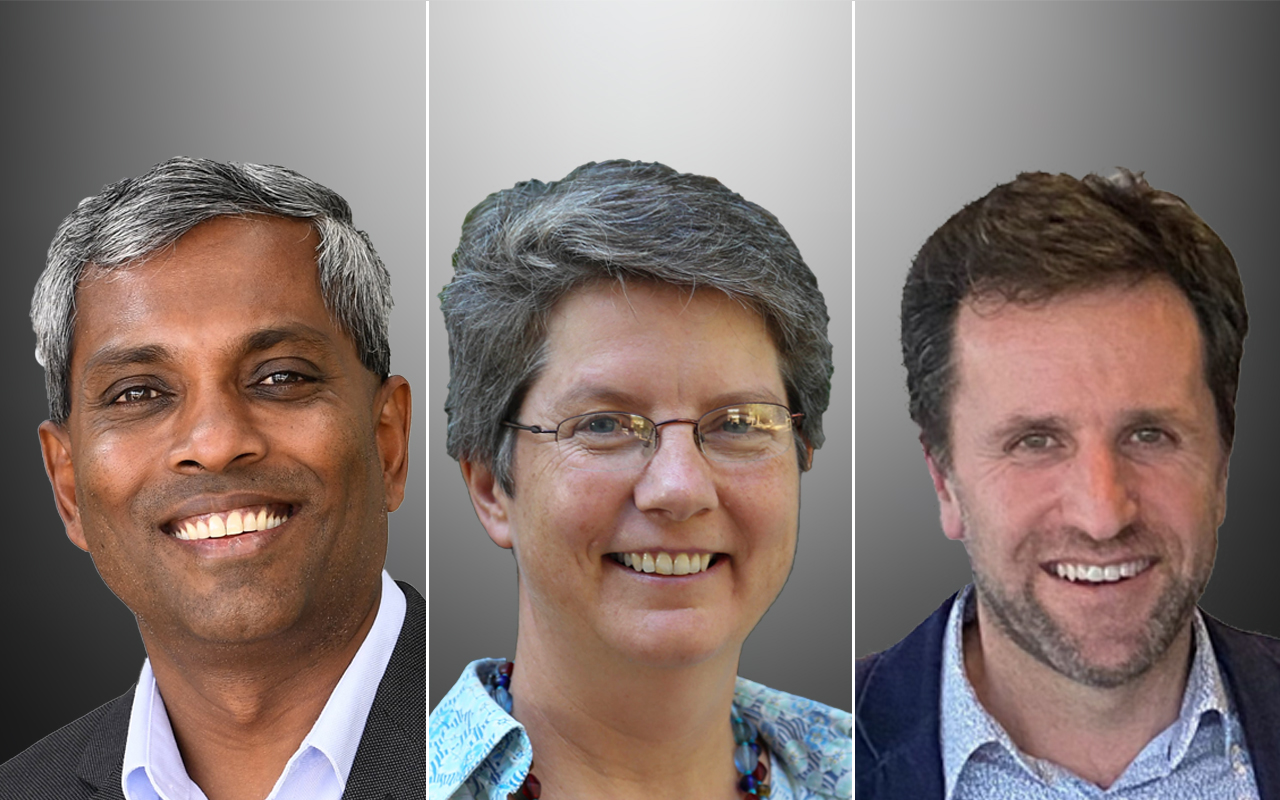

Professor Sabe Sabesan is a Senior Medical Oncologist and Chair of the Townsville Health Services Clinical Council, Townsville Hospital and Health Services, Queensland. He is interested in developing and implementing clinician–management partnership models to empower frontline clinicians in co-design of systems and quality improvement.

Professor Sarah Larkins is a GP and Director of Research Development, Division of Tropical Health and Medicine and Professor, Health Systems Strengthening, College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University. She is passionate about empowering clinicians to make the health system work better and more equitably, particularly for rural, remote and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Associate Professor Lynden Roberts is a Senior Rheumatologist and Clinical Associate Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University. He is passionate about improving clinician leadership since it is a key piece of the Australian health improvement puzzle.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Great article, as young medical students moving onto internship and beyond, I think it is very important that we learn about clinician levers and advocate to help improve aspects of healthcare and provide patient-centred care.

Great work by our old friend Sabe. Gods blessings to you and family.

Michael. Obeyesekere.