THE high burden of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people requires more active case finding and echocardiographic screening to detect undiagnosed cases, according to research published by the MJA.

The rates of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) (354 per 100 000 people in 2017) and RHD (2436 per 100 000 people) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Northern Territory are among the highest in the world; the RHD rate is much higher than for non-Indigenous Territorians (63 per 100 000 people). Many patients present with late complications of the disease and without a history of ARF.

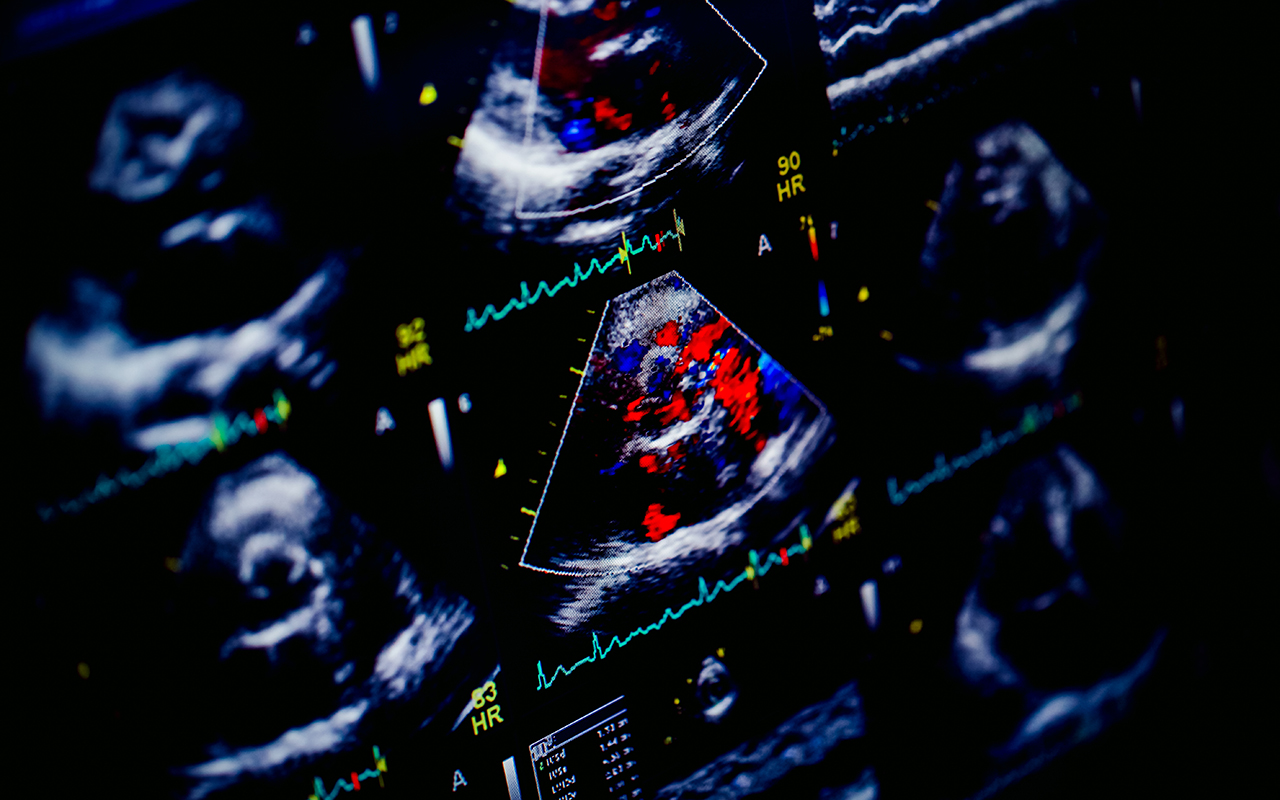

Researchers from the Northern Territory, led by Dr Joshua Francis, a Senior Research Fellow at the Menzies School of Health Research at Charles Darwin University and a paediatric infectious diseases physician at Royal Darwin Hospital, conducted an echocardiographic screening study with people aged 5–20 years living in Maningrida, West Arnhem Land (population, 2610, including 2366 Indigenous Australians) between March 2018 and November 2018.

“Definite RHD was detected in 32 screened participants (5.2%), including 20 not previously diagnosed with RHD; in five new cases, RHD was classified as severe, and three of the participants involved required cardiac surgery,” the authors found.

“Borderline RHD was diagnosed in 17 participants (2.8%). According to NT RHD register data at the end of the study period, 88 of 849 people in Maningrida and the surrounding homelands aged 5–20 years (10%) were receiving secondary prophylaxis following diagnoses of definite RHD or definite or probable ARF. The total prevalence of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease among people aged 5–20 years was at least 10%.

“Outcomes for Indigenous people with RHD are frequently poor, including heart failure, cerebrovascular accidents, and premature death; about 10% of those with severe RHD at the time of diagnosis die within 6 years. Ten-year mortality for 79 children (including 74 Indigenous patients) who underwent cardiac surgery for RHD in Melbourne was 14%.”

Francis and colleagues said their findings suggested regular auscultation and passive case finding for ARF and RHD “may be inadequate in some parts of Australia, exposing children and young people with undetected RHD to the risk of poor health outcomes”.

“Our study illustrates the importance of echocardiographic screening for RHD in a remote Australian town where, despite an established territorial RHD register and access to free health care, an unprecedented burden of undiagnosed RHD was detected,” they concluded.

“In Australia, we recommend sharing notifiable disease data and register information at the community level, so that communities with higher burdens of ARF and RHD can receive priority support for local responses, which should include support for active case finding of RHD by echocardiographic screening.”

Culturally appropriate resources needed for management of GDM in South Asian women

MORE culturally appropriate resources are needed to assist with recommended lifestyle modifications to reduce risks for future development of gestational diabetes or type 2 diabetes in Australia’s South Asian communities, according to the authors of a letter published by the MJA.

“Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is being diagnosed with increasing frequency in Australia, with the greatest prevalence reported in South Asian women,” wrote the authors, led by Dr Asvini Subasinghe, a Research Fellow at Monash University.

“South Asian women, comprising Indians, Sri Lankans, Bangladeshis, Afghanis and Pakistanis, are more likely to have GDM and develop type 2 diabetes than Caucasian women.

“Although studies have been conducted to evaluate the implementation of post partum guidelines generally in women with a history of GDM, there is no information about the implementation and uptake of guidelines in high risk ethnic populations,” they wrote.

“Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that culturally specific GDM follow-up care would increase adherence to diet and lifestyle modifications during the interconception period in high risk ethnic women.

“Therefore, as a high risk group for progression to type 2 diabetes following GDM, South Asian women in Australia should be targeted for testing, and culturally appropriate lifestyle interventions, before conception.”

GPs have a critical role in the post partum, interconception and pre-pregnancy care of women with previous GDM, and this was “even more pronounced in high risk populations such as South Asians”, Subasinghe and colleagues concluded.

“More culturally appropriate resources are therefore required to assist with recommended lifestyle modifications to reduce risks for future development of GDM or type 2 diabetes.”

Also online at the MJA

Perspective: E‐cigarette or vaping product use‐associated lung injury (EVALI): a cautionary tale

Munsif et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50691

Tetrahydrocannabinol‐containing (THC) products with vitamin E additives are implicated in the pathogenesis of EVALI … FREE ACCESS for 1 week

Podcast: Dr Eli Dabscheck is a respiratory and sleep physician at Alfred Health in Melbourne. He talks about e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury … OPEN ACCESS permanently

more_vert

more_vert

Adult women in Australia continue to be diagnosed with late presentations of Rheumatic Heart Disease using point of care echocardiography after presenting at tertiary obstetric and gynaecology hospitals, such as where I practice. Unfortunately the women newly identified with scarred heart valves are mostly Indigenous women, so often the women are pregnant and too often the women present with advanced heart failure. This is quite unacceptable. The widespread availability of point of care ultrasound has seen clinical practice change. The solution to disadvantage may not require throwing buckets of money. The solution may lie in targeted education and community empowerment. The Aboriginal Health Worker workforce in Australia are a unique health resource. Aboriginal Health Workers have been leaders in community health screening and surveillance programmes. Aboriginal Health Workers who may be an ideal group of health professionals to lead screening and surveillance services for Rheumatic Heart Disease throughout our Nation. Let us work smarter, not harder.

This finding has been known since the 1960s and early 1970s. Fifty years of massive social welfare funding for over fifty years has occurred and nothing has changed!

This is just one of many third world diseases endemic in our indigenous peoples.

Exactly the same reasons have been suggested with every new ‘study’ to hit the journals with the same responses and the same results.

Clearly logic says that after 50 years of recurrent massive bureaucratic government welfare interventions that the penny would finally drop that the never-ending cyclical generational ‘welfare trap’ does not lend itself in any way to improved healthcare outcomes (in all disadvantaged groups of peoples). Covid 19 has starkly highlighted that.

I personally believe that first people‘s recognition within the country’s constitution in some form and true reconciliation has to be in place before any sustained improvement in health outcomes will occur. Self-respect and personal value underpin everything.

A look at HTLV-3 levels (if present) in the community also should have been published in this paper.