This article is the latest in a regular series from members of the GPs Down Under (GPDU) Facebook group, a not-for-profit GP community-led group with over 6700 members, which is based on GP-led learning, peer support and GP advocacy.

ONE week ago, I had a shock while reading the Monday morning news during breakfast. An ABC article proclaimed, on the basis of new research findings, that Australian GPs commonly prescribed placebos, including inactive or inert placebos.

Among the statements was a quotation from one of the study authors: “doctors generally do not tell patients what they are getting is a placebo and genuinely think patients would benefit from it”. Even if this were a misquote given with good intentions, it can clearly be construed as a public accusation that GPs were routinely deceiving their patients. My horror deepened as I checked the source paper by Faasse and Colagiuri – it was published in the Australian Journal of General Practice, the journal of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, my College.

As I delved into the article more deeply, one set of results caught my eye: the reported use of inactive placebos. Doing simple arithmetic on Table 2 of Faasse and Colaguiri’s article, one in four participants (23%) reported using placebos at least 12-monthly, and one in seven (15%) at least monthly. The authors further report that for these GPs, they used an inert placebo for one in 20 patients. If these values are to be believed, inert placebos are one of the most frequently used interventions in general practice – an extraordinary finding!

This is where I took pause. I am not an expert in placebos, but as a clinician, educator and researcher, I do consider myself an expert in Australian general practice. In my 15 years of experience, I have never observed my supervisors, peers, registrars or students intentionally use what they perceived as an inert placebo in practice. Moreover, where are the many thousands of patients who, by implication, must have been prescribed “prepared placebo pills/capsules” and “sugar pills”? How does one even prescribe these? This result is completely at odds with my lived experience as an Australian clinician.

My doubts regarding the empirical reality of these findings might simply be a personal bias. We needed more data. I am a member of the GPs Down Under Facebook group. It currently has over 6700 members, all of whom are authenticated Australian and New Zealand GPs and GP registrars. Together, we sought to measure this quickly and robustly.

Our survey

In the afternoon of that Monday, I published a post to the group asking members to participate in an anonymous survey of a single question. This question was designed to be clear and conceptually concrete. For a therapy to be reasonably considered a placebo treatment, the intention matters. Faasse and Colaguiri themselves noted that “the physician’s intention to use a particular treatment to enhance expectations and facilitate the placebo effect – rather than to generate a specific treatment effect – are critical to determine whether a particular treatment is being used as a placebo”.

For instance, while I might consider homoeopathy to be a placebo treatment for all indications, a homoeopath would not, as they believe it to have true specific treatment effects.

Our survey asked:

“In the past 12 MONTHS have you INTENTIONALLY used an INACTIVE PLACEBO (a treatment that you believe to be THERAPEUTICALLY INERT, eg, a sugar pill for back pain) in the care of a patient?”

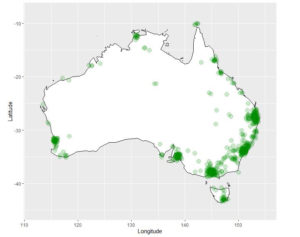

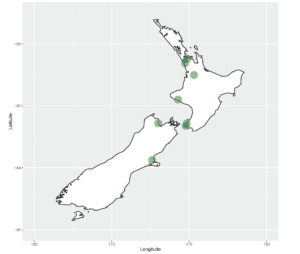

Our survey was open for 48 hours, from Monday 2 December 2019 until Wednesday 4 December 2019. There were 762 respondents, with an estimated response rate of 27% (Facebook analytics report “2.8K” members viewed the post). In comparison, Faasse and Colaguiri had 136 respondents with a response rate of 9% or 18% (“all email invitations” and “opened email” respectively). In our survey, New Zealand GPs accounted for 1.1%, Australian Capital Territory GPs accounted for 1.3%, New South Wales 26.1%, the Northern Territory 2.2%, Queensland 22.1%, South Australia 9.3%, Tasmania 3.3%, Victoria 23.4%, and Western Australia 8.1%. The following figures illustrate the distribution of respondents to our survey by their clinic postcode.

Use of inactive placebos is rare

So, what was the 12-month prevalence of use of an inactive placebo in clinical care by GPs in our survey?

|

10 out of 762 respondents, 1.3% (95% confidence interval, 0.6% to 2.4%)

|

Focusing on the vernacular and commonsense interpretation of the statement, “use of an inactive placebo”, this is neither common nor routine in general practice. It is an uncommon and unusual event.

A few members (who have given explicit permission for their stories to be shared), volunteered descriptive narratives that provide explanations of some of these contexts. One GP described working for a deputising agency, and while on a home visit, encountered a patient who was expecting an injectable opioid:

“… out of fear for my wellbeing I drew up the saline and injected it lying it was pethidine and left the building ASAP.”

Another GP described caring for a patient in a group home environment, who lived with epilepsy and frequent pseudo-seizures:

“It was not infrequent that she would fit for 5 min, then given midaz [midazolam] and would settle quickly, then trip to ED … I prescribed normal saline buccally at the one-minute mark … Patient settles now straight away with her buccal normal saline instead of midaz … Me and the staff have decided to continue that. I feel bad for prescribing placebo in this incident but I didn’t want her to get midaz unnecessarily.”

What has struck the GPs Down Under community is the seeming incompatibility between Faasse and Colaguiri and our lived experiences as a GPs. Our view is that the results in Faasse and Colaguiri are not representative of actual care delivery by Australian GPs. We acknowledge that they noted weaknesses in their methodology and its impact on generalisability in their article. Interestingly, they state that “daily survey methods” could obtain a more “acute assessment”. This of course, was the methodology employed by the BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health) study of the University of Sydney, which covered 18 years of data collection and almost 1.8 million GP–patient encounter records. A high rate of inactive placebo use is incongruous with the BEACH data.

Engage with us

It is crucial that research into general practice includes the deep involvement and engagement of GPs. The authors of the recent article are experts in placebo effects, but they are not experts in general practice. Including GP co-investigators and authors as experts of the context would have been wise. Although I believe that Faasse and Colaguiri’s survey was undertaken with nothing but good intentions, one of the sad consequences has been the distress and disenfranchisement of the GP community towards researchers.

Furthermore, the mainstream media communication would have been improved if these limitations and cautions were given more weight in the narrative. Provocative big numbers may make good clickbait, but does it achieve the intended purpose of accurate dissemination of knowledge? The GP community would be happy to engage with both researchers and science reporting in the mainstream media. However, the building of quality relationships must be based on respect, trustworthiness and reciprocity.

With us, not about us.

Michael Tam is a staff specialist at the Academic Primary and Integrated Care Unit, South Western Sydney Local Health District. He is also a Conjoint Senior Lecturer of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, UNSW Sydney. Michael’s clinical interest is in comorbid substance use disorder and mental health disorders. His research interests are in integrated care, preventive health, and medical education. He can be found on Twitter at @vitualis

Dr Karen Price is a GP in clinical practice and doing a part time PhD at Monash University. Her research is investigating the role of peer connection in Australian General Practice. She is the co-developer and facilitator of GPs Down Under, a 6500+ member community of Australian and New Zealand GPs. She has helped develop mentor programs for both the AMA and the RACGP. Karen has presented nationally and internationally; plenary lectures; workshops on women’s medical leadership; social media; resilience, and informal learning.

An explanatory note on the numbers

The labels including the term “at least” have been used inconsistently by Faasse and Colagiuri in their Table 2.

First, the labels which have been used correctly:

- Never used = 61%

- Used at least once = 39%

This makes sense. They are two mutually exclusive sets that together should sum to 100%.

However, let’s look at following sets which are also mutually exclusive:

- Less than once/year = 16%

- At least once/year = 8%

- Summed together: 24%

This doesn’t make sense as the sum of these two should equal “used at least once”, which as we’ve already established is 39% of participants.

What is the explanation? The authors have used the labels “at least once/week”, “at least once/month”, and “at least once/year” as mutually exclusive sets rather than the normal interpretation which is that they are nested sets. What I mean is, a participant who used placebos “at least once/week” has also used them “at least once/month” and “at least once/year”. This is the normal interpretation of the term “at least”.

What the authors have labelled “at least once/month” is actually, “at least once/month but no more frequently than once per week”.

What the authors have labelled “at least once/year” is actually “at least once/year but no more frequently than once per month”.

So if we want to calculate the proportion of people who used placebos “at least once a year”, in the normal way “at least” is understood, we must (i) sum the values for “once/week”, “once/month” and “once/year”, OR (ii) subtract “less than once/year” from “used at least once”.

(i)

6 (Once/week) + 14 (once/month) + 11 (once/year) = 31 participants

31 / 136 (total participants) = 22.7% –> round to 23% (no more than 2 significant values to be used given the lack of precision in the results)

OR

(ii)

53 (used at least once) – 22 (less than once per year) = 31 participants

31/136 = 23%.

Similarly, for “at least once/month”, we have to sum the values for “once/week” and “once/month”.

6 (once/week) + 14 (once/month) = 20 participants

20/136 = 15%.

more_vert

more_vert

Dear Dr Geffen,

In Medical Acupuncture we (Medical doctors) make a Western Medical diagnosis & see if Acupuncture is appropriate for treatment or as an adjunct or not at all

The Cochrane reviews are grossly flawed since they include many studies that are of very poor quality.

There is much physiological knowledge about how Acupuncture works although the mechanism is not wholly understood.

We don’t move Qi since we don’t believe that Qi exists.

Acupuncture was not based in TCM, it is much older than that.

Dr Becky Chapman

Specialist in Palliative Medicine

MA(Cantab) MB BChir DTM&H FRACP FAChPM FAMAC

Dr Price, thank you for your response unfortunately I cannot understand it all. I was not aiming to discredit your analysis or challenge your claims about how the paper in question damaged the “building of quality relationships”

Your first point in which you define a placebo as somehow not being a placebo if the practitioner believes in it strongly enough (your example of homeopathy), I have trouble with. What if a practitioner mildly thinks it might help? What if a practitioner is ambivalent? Perhaps Im not educated enough in the definition of placebo, Ive been relying on this one, which specifically describes homeopathy as a placebo regardless of whom prescribes it https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Placebo

Your second point seems to state that acupuncture (an esoteric practice founded in TCM) is supported by an evidence base when it is clearly not. Yet your (and my) college seems to believe it is not simply a placebo https://www.racgp.org.au/the-racgp/governance/committees/joint-consultative-committees/jccma despite 50 Cochrane reviews saying it is equivalent to placebo. And despite the calls of expert review bodies our college lobbies the government to pay for placebo treatments

https://ama.com.au/ausmed/acupuncture-%E2%80%93-no-point-using-it

Your third point in response to my suggestion that many GP’s use acupuncture (a placebo) in their practise relates to the statistics of the original paper which I am unqualified to challenge and defer to your judgement on. However I gleaned from your article that you disapprove of prescribing placebo (a vexed ethical issue I agree) and ask you to consider that GP’s stick tiny needles into “meridian points” to stimulate patients “Chi energy” over 400 000 times last year. I wonder how many of your 6500+ FB members are doing so?

http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/do.jsp?_PROGRAM=%2Fstatistics%2Fmbs_item_standard_report&DRILL=ag&group=173%2C193%2C195%2C197%2C199&VAR=services&STAT=count&RPT_FMT=by+state&PTYPE=finyear&START_DT=201807&END_DT=201906

Dr Myers, are you stimulating “chi energy” when you perform acupuncture? Or are you providing a slightly painful and mystical placebo?

Interestingly you have claimed an evidence base for your treatment but not mentioned the many hundreds of studies that have failed to show any benefit from acupuncture beyond placebo. For your and others benefit heres a link. Note the over 50 Cochrane reviews none of which support your claims and one that says it provides a small benefit over sham acupuncture.

https://www.scienceinmedicine.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Cochrane-acupuncture-2018.pdf

Im wondering if you perform “medical” acupuncture could you provide a rational physiological explanation of how it works (on the very rare and doubtful occasions it is better than randomly sticking little needles in the skin)?

This is a question of research merit. Asking a nuanced question with a survey is always problematic. Prescribing decisions are contextual, layered and often complex. The real question is why do GPS make the prescribing decisions they do?

To find that out, why not ask them rather than giving them options that may not represent their choices. This survey is neither a representative sample of GPs (since when can we make conclusions about behaviour with a sample size of less than 0.5% of the population) nor a qualitative study. The terms in the study are not readily understood by the cohort (never heard of active placebos) and show a deep misunderstanding of what a placebo really is.

I expect better from the researchers and the journal. This is bad science with unethical translation. Telling my patients that 80% of us prescribe sugar pills and lie to them (and that is how it will be read) is a very very poor public health message.

If Tam and Price can get four times the sample size in 48 hours, I’m afraid I hold little regard for the published study.

Dear Saul Geffen,

I am a medical acupuncturist. Medical acupuncture is evidence based medicine relying on evidence bases such as the Cochrane Collaboration recommendations that patients with tension type headache and migraine headache should be offered a course of acupuncture, because, pragmatically, these patients will have 21 less headache days per year, even a year after the acupuncture treatment has ceased,

Similarly, in the Vickers et al meta-analysis of acupuncture treatment of chronic pain true acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture and waiting list controls, and in the MacPherson et al long term follow up of acupuncture in chronic pain, the beneficial effects persisted even 1 year after treatment had ceased. Medical acupuncture is a reasonable treatment option for Australian patients. It has Level 1 peer reviewed evidence of benefit.

The main problem here is the word “placebo”. Even more problematic are the designations “active placebo” and “inactive placebo”. There is also the difference in the meaning of a “placebo” used in clinical trials, where the placebo covers all effects of a drug apart from its actual pharmacological effect. This includes “regression to the mean”, “expectation bias”, and “experimenter degress of freedom” and many other effects appropriately called “placebo effects” (plural). Until this confusion is sorted out and everyone agrees on the actual definitions, we should take the outcome of all these reviews with a large grain of salt.

I should also point out that the idea that placebos are very effective is incorrect on a number of levels. It is true that they can help to reduce psychological dimension of subjective symptoms such as pain, vomiting, anxiety and depression, but their effect is unreliable, limited, and of short duration. But they have no effect whatsoever on objective measures or on the underlying pathology. This includes the placebo effects of homoeopathy, acupuncture, and chiropractic (over and above the positive effects of massage). Moreover, reliance on treatments that use only the placebo effect can delay proper treatment and proper diagnosis and leave the patient vulnerable to other forms of alternative medicine which are positively harmful, including anti-vaccine propaganda.

Really interesting article Michael and Karen. I wonder about the responsibility of the journal peer review process and editorial team in this. Peer reviewers are expected to be ‘experts’ in the area, and a consensus of a minimum of 2 reviewers and the managing editor is generally required for publication, serving a gate keeping role. The process should ideally have addressed the issues raised here; why didn’t it?

From my perspective, there is a real paucity of clinician-researchers, and a definite paucity of GP clinician-researchers. This means the existing pool are really overburdened by requests to peer review, often in areas outside their expertise. Wonder whether this is consistent with the GPDU group’s experience?

Thanks for the sharing this, really great points raised.

The lactose tablets in the COCP are not placebos – they are inert.

No one has ever implied that they serve a pharmacologically beneficial effect. They are simply spacers designed to improve compliance.

This publication is indicative of major problems, notablya serious lack of understanding of the placebo response, its proper use and interpretation.

There is a sophisticated knowledge base for the study of the placebo effect, conducted with good quality scientific principles.

Try Benedetti, and Lorimer Mosely.

I do not understand the concept of ‘inactive’ placebo. Somebody is kidding themselves.

There is no facet of medical practice that can be conducted without Expectation and Conditioning affecting the outcome, hence a placebo effect, except perhaps post-mortems….

The effect is active, positive or negative, even before actually attending an appointment.

As one of the original study authors, I have contacted the InSight Editorial team to request a formal right of reply, which the Editor has agreed to publish. Unfortunately, as this is the last issue of InSight for 2019, our formal reply cannot be posted until Monday 13th January, 2020.

Until then, I would like to note two things:

1. There is no inaccuracy or inconsistency in the numbers we reported in Table 2 of our paper. Fifty-three (53; 39%) of GPs surveyed said that they had *ever* used an inactive placebo in clinical practice. Tram and Price misrepresent this data by suggesting it is inconsistent because we reported that 22 (16%) reported using an inactive placebo “Less than once/year” and 11 (8%) reported doing so “at least once/year”, which of course sums to 24%, not 39%. The obvious explanation is that there were other response options, namely “at least once/month” (14; 10%) and “at least once/week” (6; 4%). When summing all of these values the total is 53 respondents, i.e. 39% of 136 respondents*. It is misleading to suggest that there our data were inconsistent when the full table makes it clear that there were other response options.

*The only minor aspect that might *appear* inconsistent is that the sub-percentages do not add precisely to 39%, i.e. 16+8+10+4 = 38%, which is a simple function of rounding.

2. A full (unedited) interview regarding the study on ABC News 24 can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GGhbXci2oMk&feature=youtu.be. I will leave it to readers to judge whether there was any “public accusation that GPs were routinely deceiving their patients”.

More in January…

Good article – we need more GP researchers. RACGP should have requirement of publication/research as part of fellowship and should have more primary research CPD activities.

Dear Dr Geffen

Firstly the article directly answers your question

“For a therapy to be reasonably considered a placebo treatment, the intention matters. Faasse and Colaguiri themselves noted that “the physician’s intention to use a particular treatment to enhance expectations and facilitate the placebo effect – rather than to generate a specific treatment effect – are critical to determine whether a particular treatment is being used as a placebo”.

For instance, while I might consider homoeopathy to be a placebo treatment for all indications, a homoeopath would not, as they believe it to have true specific treatment effects.“

Secondly

Traditional Chinese medicine is not considered a curriculum topic of the RACGP without an evidence base.

Thirdly

One of the forums objections towards the original article was the assertion that based on n=136 the media communication message became “80% of GPs prescribed placebo”. Apart from the definitions and the limited sample size which is underpowered for that assertion —the messaging and Science communication was poorly delivered.

So there were several issues this rapid response to the original study answered. I believe there was an ethical frame desired by the original authors and that nuance of the art of medical delivery which occurs in all parts of specialty medicine including the specialty of General Practice was somewhat lost in the discourse and study design.

The word “deceitful” was used in media reporting which is an ethical anathema I believe, to most GPs and indeed most medical practitioners.

See here. http://medicalrepublic.com.au/gps-reject-claims-deceitfully-prescribe-placebos/24348

Lots of GP’s use placebo. In fact anyone practicing Traditional Chinese Medicine including acupuncture is largely (and in some cases exclusively) relying on the placebo effect. Perhaps the author could ask her Facebook group how many of the members do “medical” acupuncture.

There is evidence that placebos can be beneficial even if they are ‘open’ placebos.

I have used open placebos ie. I tell the patient that “it is ‘fizzy vitamin C’ but that it may help”.

Thanks for the question. The reason I only asked about inactive placebos in this survey as this was a rapid response. My intention was not to test or challenge every estimate in the original paper. The problem with “active placebos” is that it is a conceptually complex notion that arguably does not dichotomise well into binary “yes” and “no” answers. However, inactive placebos are much simpler to define in the question, and thus, the binary responses are more concrete. Simply, it allows us greater confidence that our commonsense and common language interpretation of the meaning of the question is reflected in the responses.

Why only ask about inactive placebos?

The GP interviewed on the ABC advised he also used antibiotics as placebo.

Good work Michael

Doctors do sometimes over read questions. There also needs to be an explanatory note that this does not include the sugar pills in the 28+ day oral contraceptive pill packs

Wondering how many of the participants thought of this and put it down

Prescribers would be close to 100% if surveying a GP audience but the data would be meaningless