THE Australian Medical Association’s Code of Ethics, among other things, encourages doctors to consider the resources they use when treating patients by providing care that is notable for:

“ … effective stewardship, the avoidance or elimination of wasteful expenditure in health care, in order to maximise quality of care and protect patients from harm while ensuring affordable care in the future.”

A little parsimony in one’s day-to-day work is obviously important, yet every doctor experiences the dilemma of whether to provide a patient with care that is unlikely to be cost-effective. Health economist Victor Fuchs has termed this the “doctor’s dilemma”, describing the situation where patients sometimes want:

Just how important is it that doctors manage patients with an eye to the health budget? Indeed, how are practitioners even to know which treatments are the most cost-effective? For a condition as common as hypertension, cost-effectiveness analysis is challenging and the results depend on multiple factors, including age, other comorbidities, and even patient gender. Such analyses become even more complicated with invasive procedures such as bariatric surgery, where the costs of an operation are high, yet weight loss is rapid and patients become more productive and less likely to need other operations, such as joint replacement.

Medical care is different

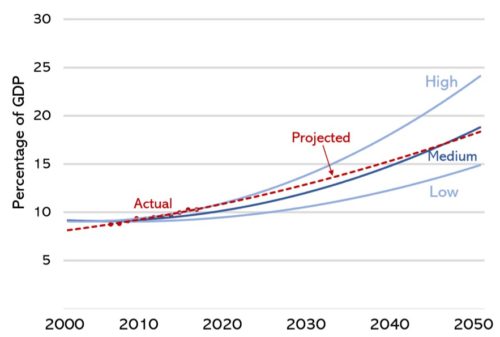

American health economist Jonathan Gruber makes an important observation: while in other parts of the economy technological improvements tend to make goods and services less expensive and more efficient (think about what your television can do now compared with the one you had 10 years ago), in health care “new technology makes things better, but more expensive”. The same is true in Australia. In 1960, health spending made up less than one-twentieth of the Australian economy. Today it accounts for about one-tenth of the total Australian economy and is projected to grow to almost one-fifth by 2050 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Predictions from the early 2000s of health expenditure in Australia as a proportion of GDP, based on data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, with estimates based on optimistic (low), realistic (medium) and pessimistic (high) assumptions about the economy and people’s health. We ran second-order polynomial regressions that yielded R-squared values of >0.97 to continue the AIHW projections out to the end of 2050. Shown in red are the actual figures, with a projection.

Increased healthcare spending should not be surprising: nations with higher incomes tend to have larger health care sectors than poorer nations. Australian voters rank health spending as their number one priority for government spending. But there are good reasons to think that our healthcare system can become more productive. In its 2017 Shifting the Dial report, the Productivity Commission outlined 28 recommendations to boost productivity across the economy. The first six recommendations were on health.

To complicate things further, healthcare seems poised on the cusp of a series of revolutions that make expenditure predictions very difficult. Artificial intelligence (AI) is being introduced into clinical care, particularly in areas such as imaging. A growing body of research is demonstrating the value of “personalised” or “precision” medicine, where information about a patient’s genome and other factors allows more precise tailoring of preventive and therapeutic efforts. At this stage, it is not clear whether advances such as AI and genomics are likely to decrease or increase healthcare costs. According to a review published last year:

“In theory, the economic case for precision medicine can improve the relative cost-effectiveness of care by exploiting patient-level heterogeneity in cost and health outcomes. In practice, deficiencies in the (clinical and economic) evidence base, and the plausibility of assumptions, may make the economic case for precision medicine a challenge to demonstrate.”

Similarly, advances in genetic diagnostics and pre-pregnancy screening have the potential to change population epidemiology of inherited conditions such as spinal muscular atrophy. Over the next generation, will technologies such as CRISPR allow us to edit our genomes at conception and lead to alterations in the natural history of non-communicable diseases? Will our concerns about the risks of germ line editing be overwhelmed by the potential health benefits? More prosaic concerns also will play out over the next 20 years. The population is ageing, and people older than 65 years use four times the health resources of younger people: those aged 85 use three times as much as those aged 65. The most recent Commonwealth Treasury Intergenerational Report predicts that the number of people aged between 15 and 64 years for every person aged 65 years – estimated at 4.5 people today – will drop to 2.7 people over the next 30 years.

Healthcare is beneficial … usually

It is easy to point to past medical breakthroughs that have reduced mortality and improved the quality of life. Penicillin and beta blockers, hip replacements and humidicribs are among thousands of innovations that have made Australians healthier. Deaths from chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, cancer and diabetes have fallen considerably since the late-1970s. Australians who are healthy enjoy more productive lives, and are more likely to contribute to the economy and thus fund healthcare.

Yet adding unhealthy years of life adds to the cost of care, whether in the formal paid economy or the informal unpaid economy. There is also a risk that market concentration — commonly is associated with increased costs on the demand side – will lead to Australian consumers and taxpayers overpaying for new developments. This has been a feature of the US healthcare system, and there are signs Australia is following suit. The largest four firms have an 89% market share in pathology, 79% in pharmaceutical wholesaling, 72% in health insurance, 66% in private hospitals, 59% in pharmacies, and 46% in diagnostic imaging.

For all these reasons, it is inevitable that doctors will need to think about whether the care provided for each patient is not only clinically effective, but also cost-effective.

The “doctor’s dilemma” – the pressure to provide care irrespective of economics – inevitably leads to prescribing more treatments and ordering more tests. In Australia, the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) comprises about one-third of all Commonwealth Government health spending. Questions about the value of treatments and tests have led to the MBS Review. However, the review process has highlighted just how difficult it is to adjudicate on cost-benefit. With the MBS encompassing thousands of items, it has become clear that many of these will never have level one evidence underpinning them. Even when there is agreement among experts about the evidence base, practice may diverge.

How can economists work with medical practitioners?

Economics is the science of scarcity: how we maximise the benefits available from the resources we have and, particularly with health economics, recognising the principle of equity and fair distribution of these resources. For the majority of doctors, care decisions are made individually – one patient at a time. For the health economist, these decisions are made, “against a background of limited health care resources, an empowered consumer and an increasing array of intervention options [with] a need for decisions to be taken more openly and fairly”.

Is it possible to reconcile these two paradigms? Can health professionals and policymakers work together, seeking to ensure that Australia gets the greatest bang from our medical buck?

One barrier is the language used by health economists, terms unfamiliar and different from those doctors use with their patients. As an example, “moral hazard” is the concept that health insurance coverage, by lowering the marginal cost of care to the individual (often referred to as the out-of-pocket price of care), may increase healthcare use. We recognise this from our everyday experience: in Australia, 87% of patient treatment episodes occur with no out-of-pocket cost to patients, making it tempting to ignore treatment costs. Yet these costs invariably are paid somewhere in the system.

Another economic concept is that of “opportunity cost”: what else could be achieved if the money spent on a treatment was, instead, spent on something else? To further add confusion for health professionals, opportunity cost may be measured in units such as “QALYs” (quality-adjusted life years) or “DALYs” (disability-adjusted life years) – how much more quality, or disability-free, time could be gained for people if some other treatment (or no treatment at all) had been delivered?

When services are funded by governments, the opportunity cost usually is not immediately clear. If the health budget remains constant, then the opportunity cost of providing ineffective care is likely to be that a promising new treatment cannot be subsidised as quickly as would otherwise occur. If the health budget grows, then the opportunity cost will either be that other areas of the budget must shrink, or taxes must increase. Further complicating matters, healthier people are more likely to contribute to the economy and pay for their own care.

Whenever doctors provide care of questionable benefit, it places upwards pressure on health insurance premiums. As the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission recently observed, “private health insurance participation rates continued to decline, while gap payments for in-hospital treatment increased”.. As healthy people – those unlikely to make large claims for care – relinquish private health insurance and use the public hospital system, this not only increases pressure on public hospitals but also leaves a smaller pool of less healthy insured patients who are more likely to make claims for private care.

Few doctors want to provide ineffective care to their patients: yet unequivocal evidence on exactly what care is both effective and cost-effective for a single condition can be maddeningly difficult for even the experts to agree on, as the MBS Review has shown. Adding these therapeutic uncertainties across multiple conditions in a single patient, let alone for every patient in a practice, is an almost impossible task. While most Colleges provide regularly updated general guidance on how to manage important and common clinical conditions, slavish and uncritical adherence to such guidance has its own potential adverse consequences.

Predicting the future is hard

As healthcare expenditure inexorably accounts for more of our nation’s spending, so it becomes ever more important that doctors and economists develop a good working relationship rather than endure a “shotgun marriage”. Consider the area in which AI is likely to impact healthcare most directly – computer decision support. Clinicians are unlikely to be able to develop the technology necessary to deliver AI-powered decision support systems. Nor are economists likely to grasp the clinical nuance required to make such systems intuitive, helpful, and patient-centred. Neither group would want a purely data-driven system delivered by technical AI specialists.

Such systems strike us as an ideal starting point where economists and doctors can collaborate to use data permanently residing in electronic medical records, combined with AI that integrates other data (such as past hospital episodes) along with decision-support that occurs seamlessly – perhaps with AI-driven ambient “scribes” – to optimise interactions. For such systems to be acceptable, patients will need to be confident and trust the system, and doctors would need to feel supported. For example, if they fail to order a test because the AI recommended against it, then they should not face a penalty if an important condition is missed.

Decision-support is one potential example of encouraging “digital maturity” – the thoughtful integration of clinical experience with AI and other technologies – in patient care. The challenge of these technologies is ensuring that the time penalty of interacting with the system doesn’t impede on already pressured patient contact. Perhaps most importantly, any perception of interference in the doctor-patient relationship would be anathema to both doctors and their patients. Patients don’t want to think that health care is being rationed or dictated by impersonal economic algorithms.

Ultimately, it is important to recognise that the challenge of ensuring cost-effective care is the responsibility of all of us – patients, doctors and policymakers. Expecting doctors to carry out an economic cost-benefit analysis on every treatment would be as foolish as expecting drivers to carry out an engineering calculation every time they drive down a new road. Instead, drivers are required to know some basic rules, and are kept safe by experts who design roads to maximise safety and traffic flow. In the case of healthcare, the focus should be on building systems that maximise the quality of care delivered for each additional dollar of health care spending. That’s something that doctors and economists definitely can agree on.

Professor Steve Robson is immediate past-President of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and a member of the Australian Medical Association Federal Council. Until recently, he was a member of the MBS Review.

Dr Andrew Leigh is an Australian politician, author and former professor of economics at the Australian National University. He has been a Labor member of the Australian House of Representatives since 2010 representing the seat of Fraser until 2016 and Fenner thereafter.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert