A new study from Monash University demonstrates that parental concern that their child is deteriorating is a stronger, and sometimes earlier, predictor of ICU admission than abnormal vital signs.

“Patients don’t suddenly deteriorate. Health care professionals suddenly notice.”

– Dr Patrick Brady, Cincinnati Hospital

Failure to adequately respond to caregiver concern has been a recurring theme in recent high profile paediatric deaths such as those of Aishwarya Aswath (rapidly worsening sepsis while in the emergency department [ED] waiting room), Kyran Day (intussusception mistaken for gastroenteritis), Ryan Saunders (Group A streptococcal sepsis), and Luca Raso (appendicitis mistaken for “gastro”).

Early stages of life-threatening conditions can mimic benign (and much more common) childhood illnesses. Sepsis can initially appear similar to common viral illnesses; surgical pathology (such as appendicitis or intussusception) can mimic gastroenteritis; and breathing difficulty due to severe asthma can mimic a panic attack.

Failure to recognise, or delay treatment, of any life-threatening illness may be associated with serious adverse outcomes.

How good are we at recognising sick children?

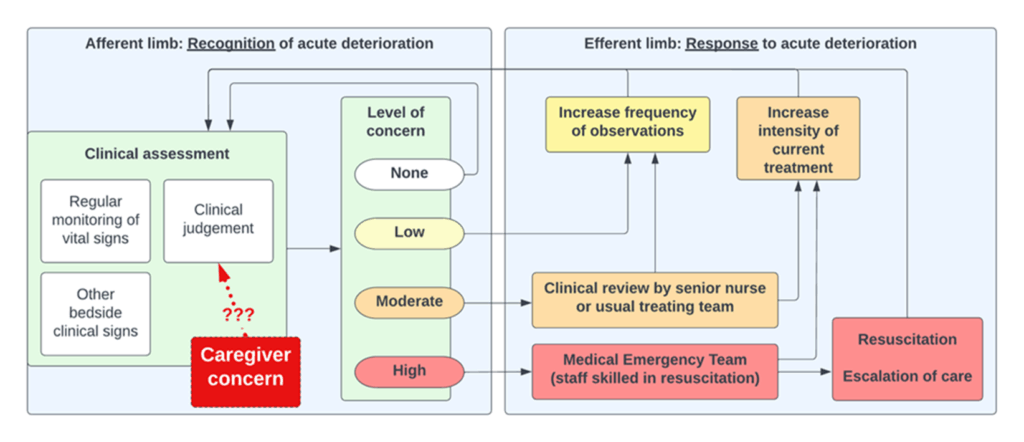

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) requires that appropriate and timely care is provided to patients whose condition is acutely deteriorating. Hospital-based recognition and response systems have afferent (designed to recognise clinical deterioration) and efferent (responding to clinical deterioration) limbs, aimed at reducing the risk of a serious outcome. However, despite widespread use of these systems, coroners’ reports and other reviews repeatedly describe failure to take heed of parental concerns as a major contributing factor to delayed recognition and treatment of serious illness.

In recent decades, the activation of recognition and response teams has focused on repeated physiological measurements. These clinical findings are repeatedly measured (tracked) until they cross a threshold (either through a scoring system that allocates points to a combination of factors, or an abnormality in a single measurement) to trigger a rapid response from staff trained to provide critical care (Figure 1). However, relying on a system using physiological measures alone may be unreliable and insufficient.

How can parents and carers help us recognise the child with a life-threatening illness?

Families’ unique knowledge of their children may enable them to recognise subtle changes in behaviour or temperament before the most expert clinician, and before there are clear signs of clinical deterioration. Despite this, a 2020 systematic review assessing consumer escalation in the hospital setting found that (a) the ability of consumer escalation processes to achieve their underlying goals is still to be adequately assessed, and (b) further research is required to inform how to best implement, support, and optimise consumer escalation systems.

We set out to determine whether caregiver concern for clinical deterioration is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalised children.

In 2020, in response to critical incidents in our health service, a multidisciplinary team launched an initiative, co-designed with consumers, to improve the involvement of patients and families in recognising serious illness in children. Clinical staff in the emergency department and inpatient paediatric wards were directed to ask the caregiver (parent or other responsible adult) accompanying the child ‘‘Are you worried your child is getting worse?’’ before every set of vital signs taken after triage. The program was rolled out over a series of educational sessions, and the electronic medical record was adapted to allow recording of the caregiver’s response. If the concern related to clinical deterioration, local escalation procedures were followed.

Listen to the parents!

Our findings, recently published in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, confirm what we have always been taught, but often forget to apply in practice: listen to the parents!

We analysed data on over 24 000 children over a 26-month period, and identified nearly 190 000 responses to the question about concern for deterioration. Of these, under 5% of caregivers reported concerns. Compared with patients with caregivers without documented concerns, children with a caregiver reporting concern for clinical deterioration were more likely to be admitted to the ICU (6.9% vs 1.8%), to be mechanically ventilated (1.1% vs 0.2%), or die during admission (0.1% vs 0.02%). After adjustment for other variables, caregiver concern was more strongly associated with ICU admission than any abnormal vital sign.

In about 19% of cases, caregiver concern was noted before any abnormality in vital signs, with a median time from first documented concern to first abnormal vital sign of over 7 hours.

Including patients and caregivers in clinical decision making improves the safety and quality of care. This new evidence demonstrates the importance of parents and caregivers as crucial resources to assist clinicians to monitor for deterioration, and suggests they might even be more effective than current systems that rely solely on vital signs.

What’s next?

Effective implementation requires more than a poster in the waiting room.

We believe that proactive assessment for caregiver concern should be a standard component of clinical care, with concerns integrated into hospital systems designed to detect deterioration.

Future directions include wider implementation across children and adult patients in various settings, determining the relationship between caregiver concern and specific serious conditions such as sepsis, determining the potential impact of incorporating caregiver concern into early warning systems, and innovative solutions such as smartphone apps to further support patients and families navigate the escalation process and become embedded as part of the care team.

Conclusion

Parents and other caregivers are experts in their own children. The challenge now is to set up systems to harness this expertise, and work in partnership with families to improve the quality and safety of care we deliver.

Dr Erin Mills is a paediatric emergency physician at Monash Medical Centre and clinical advisor – quality and patient safety, Monash Health.

Ms Phyllis Lin is a data scientist in the Department of Paediatrics, Monash University and the Paediatric Emergency Department, Monash Health.

Associate Professor Mohammad Asghari-Jafarabadi is a biostatistician at the Biostatistics Unit, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine and Department of Psychiatry, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University.

Dr Adam West is a paediatric emergency physician and director of Paediatric Emergency Medicine at Monash Health.

Professor Simon Craig is a paediatric emergency physician at Monash Medical Centre and adjunct clinical professor in the Department of Paediatrics, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Thank you for a timely & important study.

As a parent of a child with a significant congenital anomaly requiring repeat procedures,

adding to more limitations, I confer parents know best.

My son went on to achieve full independence, post graduate education & full employment. As a family we know this could not have been achieved without the expert care and compassion of colleagues.

Thankfully as a profession, we strive to do better more so understand the importance of continuing education & research outcomes by experts. We must therefore always remain mindful that parents’ concerns matter greatly.