In medicine, we’re good at showing up to do the work no matter what. But we’re far less skilled at saying, “I’m not okay.”

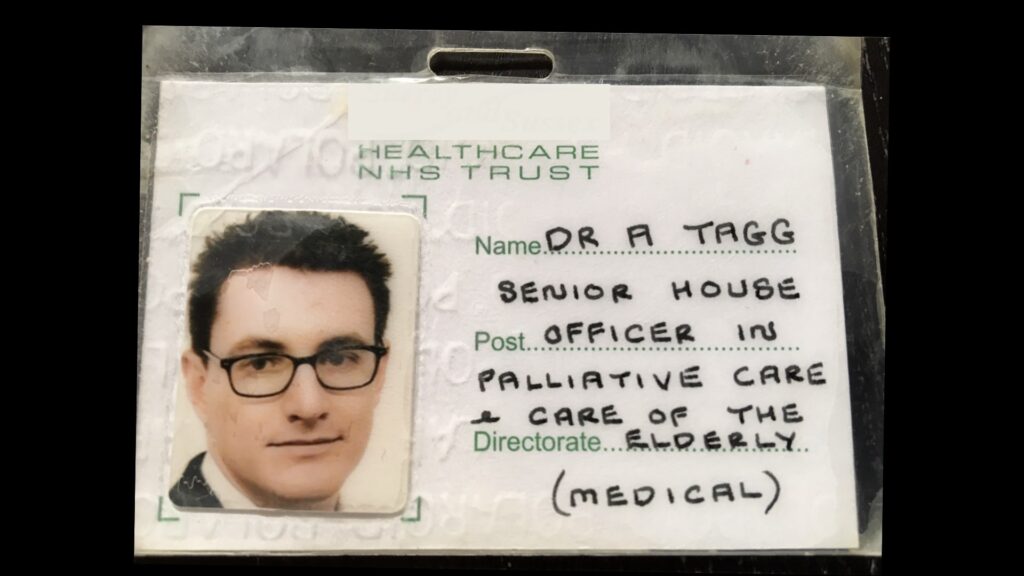

This is me, smiling. Clean-shaven. Early 30s. The photo on my hospital ID badge — the one I clipped to my shirt every day. I looked like I had it all together.

What you can’t see is that during the year that photo was taken, I tried to kill myself.

I don’t say that lightly. And while I’ve spoken about it once or twice, it’s not something I talk about often.

That year, I wasn’t working in a high pressure trauma unit or a chaotic emergency department. I was working in aged care — a job marked by slowness and routine, where each day blended quietly into the next. I spent my time talking to residents, helping with medications and filling out paperwork. On paper, it should have been one of the quietest, kindest years of my career.

But inside, I was quietly, invisibly falling apart.

In medicine, we’re good at showing up. No matter what’s happening in our personal lives — relationship breakdowns, exam failures, exhaustion — we turn up, we do the work, we tick the boxes.

But we’re far less skilled at saying, “I’m not okay.”

Even in that near-nursing home environment, where the pace was slow and the days blurred into one another, the silence was the same. I felt ashamed of how I was feeling. Ashamed that I couldn’t just push through. Ashamed that my mind — the very thing I relied on to care for others — had turned against me.

No one at work knew. I didn’t tell them. Not because they wouldn’t have cared, but because I didn’t know how to let the words out.

There’s this unspoken code in medicine:

You can be weary, but not weak.

You can be sad, but still seen as strong.

But falling apart? That’s not part of the script.

I didn’t have a single breakthrough moment. There was no dramatic turning point, no overnight recovery. What helped was much harder — and much more honest — than that.

It started with a phone call from a friend. An admission to hospital. Followed by years of taking tablets.

Not easy things. Not things I wanted to do. But things that kept me here.

Some days, I just waited the feelings out. Some days, I let them wash over me. And some days, I surprised myself by laughing at something dumb on TV.

Eventually, I started to believe I could survive. Not thrive. Just survive. That was enough.

There were times when I kept going only because I couldn’t bear to disappoint the people who loved me. Sometimes that guilt tethered me to life. Sometimes it was just the rhythm of a day — meals, movement, moments — that carried me through.

Looking back, it wasn’t strength that saved me. It was structure. Medication. Connection. And the decision — made over and over — to stay.

These days, it’s easier to talk about it. I have the words. I have the distance. I’ve survived.

But back then, I didn’t want to be seen. Not like that.

It’s tempting to believe that openness is the answer — that if we all just shared our stories, the stigma would lift and things would get better. But when you’re at your lowest, asking for help feels impossible. You don’t want to be a burden. You don’t think you’re worth saving. You can barely get through the day, let alone put your pain into words.

I think about that a lot now, especially around days like #CrazySocks4Docs. It’s one thing to wear the socks. It’s another thing entirely to reach out when you’re the one who’s struggling.

We say, “Check on your strong friends.” But maybe we also need to make it easier for them to whisper before they break.

This isn’t a story with a neat ending. I didn’t conquer anything. I didn’t come out stronger. I’m just here — still doing the work, still sometimes struggling, still sometimes helping others do the same.

But I know now how much it matters to be able to say, “I need help.”

And I know how much it matters to hear, “I’ve been there too.”

If you’re the one barely holding it together, I hope this makes it feel a little less lonely. If you’ve never felt that low, I hope it makes you look around a little more carefully.

We don’t need more slogans. We need more softness. More small check-ins. More moments of truth.

And we need to remember: the colleague who seems calm and competent might be carrying more than you can see.

I was.

I still have that ID badge.

It sits in a box with other relics from that time — pay slips, old rosters, the kind of paperwork you keep without knowing why. I used to look at it and feel ashamed. Now, I see it differently. It’s proof that I made it through a year I wasn’t sure I’d survive.

Recently, it was CrazySocks4Docs — a day to raise awareness about the mental health of doctors. It’s easy to join in with a colourful pair of socks. It’s harder to say, this was me.

But maybe, just maybe, sharing that might help someone else get through their own impossible year.

A/Prof Andrew Tagg is a Paediatric Emergency Physician at Western Health in Melbourne. He is Deputy Chair of the ACEM Workforce Wellbeing Network and a strong advocate for mental health in medicine.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

If you or anyone you know needs help:

- Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

- Lifeline on 13 11 14

- Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander crisis support line 13YARN on 13 92 76

- Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

- MensLine Australia on 1300 789 978

more_vert

more_vert

Thankyou for sharing your story Andrew you’re absolutely right in saying it’s so hard to say I’m not okay. As a healthcare worker going through cancer and treatment after nearly 12 months I stay strong and focus on a positive outcome for myself and my daughter.

I suffer for many years. Did not dare to look for help until my marriage broke down. Went through, and now pass, the stage of being considered as impaired Dr. and still being hounded by the regulators.

Thank you, Andrew, for sharing your insights. I’ve had the pleasure and privilege of hearing you speak, and I often reflect on your talk during challenging moments, as it reminds me that I am not alone in my struggles.

As a consultant in my field, I’ve found myself increasingly grappling with significant stress, often at a considerable personal cost. It seems many colleagues, support staff, AHPRA, and even patients don’t fully grasp the immense pressure we face. There’s an expectation that we should always remain strong and dedicate our lives to others, rather than simply working with passion and commitment.

While I manage most days, there are times when I don’t, and I often find that those around me don’t notice. Simple gestures, like a smile or a show of kindness, can truly make a difference and help lift someone from a dark place.

Thankfully, my family and dogs are always there for me.

Writing and speaking from a lived experience position is so powerful. Thank you. You have probably helped more people than can be imagined.

Sometimes its not only situational but biochemical. Diet is not nutritious and many of us lack B12, Zinc, Magnesium, Vit D, omega 3, Iron etc which all contribute to mood problems. The medical profession is fairly resistant to the idea of nutrition linking to disease.

Thanks Andrew. You may not know how many people, or who, you have helped, thanks to your honesty and generosity.

Thanks for this .. honest and true reality.

Major issue i personally experienced was Everytime I said we need to see someone, the answer was I will lose my job. Non of the organisation the drs work with are for them all are against them, the law maker, the registration, exam providers, AMA, RACGP, AHPRA, ACCRM and on and on and on

Yes it’s wonderful that you survived Dr Tagg, it’s not only Doctors that experience this, but I’m sure your pressures are much larger than those of a Healthcare Worker! I too have had these terrible thoughts but unfortunately I have a huge amount of allergies so the medication I was prescribed did not help it make me sick! It was a comment made from my older Son that snapped me back to reality slowly… I’m very lucky & grateful for his wise words, although very embarrassing it changed our relationship into a much be closer! Although I still feel guilty today & this was in 2006.. the guilt does subside..

Thank you for sharing.

Small check ins matter.

And it’s true that those that seem strong might actually be going through Hell.

Doctor’s mental health matters.

Great Article Andy- you’re a legend for advocacy; and a hero for sharing your story ; why’s is another step in destigmatising the struggle that affects as all either directly in community ❤️

Thank you for your courage in sharing your journey. You describe it all so well. How we are trained to show no weakness. How it’s impossible to ask for help. It’s a good day if we get out of bed. How we have to decide over and over again, often multiple times a day, to stay alive.

Congratulations on getting back to work.

Thank you for sharing Andy and taking the time to write this. Every time you do, and you do it so generously, and always with such humanity and heart, your story it reaches someone who really needs it, and in fact it reaches many people over the years who need it. X

Thanks Andy

Yes the conversation ,the initial is hard probably the hardest

Thanks as always with your story sharing it will help

Best

Geoff

Me too

Thank you so much for sharing your story Andrew. It goes a long way in helping highlight the barriers doctors and other health professionals face . And will no doubt give others the courage to speak up and colleagues to check in .

There are many people, some doctors, who need a doctor like Dr Tagg. Takes guts and much altruism to reveal your inner self in the hope of helping others hiding in the same boat.

I was there too

Thank you, Andrew.