This article was originally published as a Perspective by the Medical Journal of Australia on Monday 23 August 2021. Republished with permission. Read the original here.

“CONTINUITY of care” refers to the holistic management of a patient by a single practitioner, or a well integrated network of practitioners in close communication. The definition of fragmented care is not established, but here we consider it to be three or more different GPs managing the same underlying condition or presenting complaint.

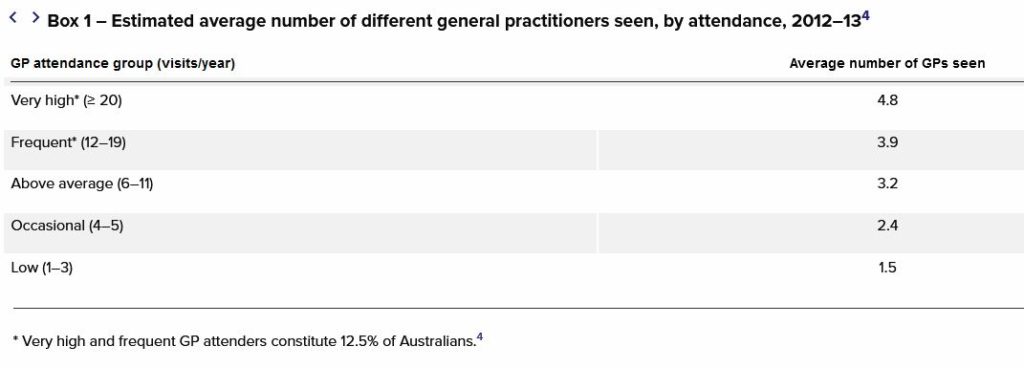

There is a substantial body of literature that demonstrates the benefit of care continuity with respect to patient satisfaction, reduced mortality and reduced avoidable hospitalisation. However, we know that despite its importance, continuity of care with one practitioner is often lacking (Box 1), and the risks associated with fragmented care are not well described.

Source: National Health Performance Authority. Healthy communities: Frequent GP attenders and their use of health services in 2012-13.

In this case review, we used the medico‐legal case files from the largest Australian medical defence organisation (Avant Mutual) in an attempt to identify the underlying contributors to, and negative consequences of, fragmented care.

Avant Mutual case files are a mix of complaints to Australian medical regulators, compensation claims alleging medical negligence, and coroners’ cases. Case files from the past 5 years were filtered for cases in which multiple doctors were considered to have contributed to the adverse outcome. This produced 45 case files, which were reviewed in full to determine inclusion criteria (three or more GPs involved in the adverse outcome). Fourteen cases were relevant and included in our analysis. Ethics approval was granted by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners National Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee (HREA ID JM03085).

Our review revealed three key areas where fragmented care was associated with adverse outcomes:

- delayed or missed diagnoses;

- inappropriate prescribing; and

- failure of preventive medicine.

Delayed or missed diagnoses

In multiple cases, serious conditions were diagnosed late in their natural history, following fragmented care. In some cases, upwards of 10 GPs were involved. We identified common themes in pathology, patient and clinician factors.

Pathology factors

Missed pathology reflected a difficult triad of features. In most cases, the pathology was uncommon or rare. It had a natural history defined by slow, insidious evolution of symptoms; and the symptom profile was non‐specific, with the result that symptoms were easily attributable to more common, less serious pathologies.

Patient factors

Patients involved often had multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy, including active mental health issues, chronic pain and substance misuse. The difficult dynamics of these consultations appeared magnified when multiple GPs were involved, each attempting to contribute to complex management of chronic conditions. Occasionally this was coupled with challenging patient behaviours, increasing the temptation for a shorter consultation and “moving the patient on” to their “usual” GP.

Clinician factors

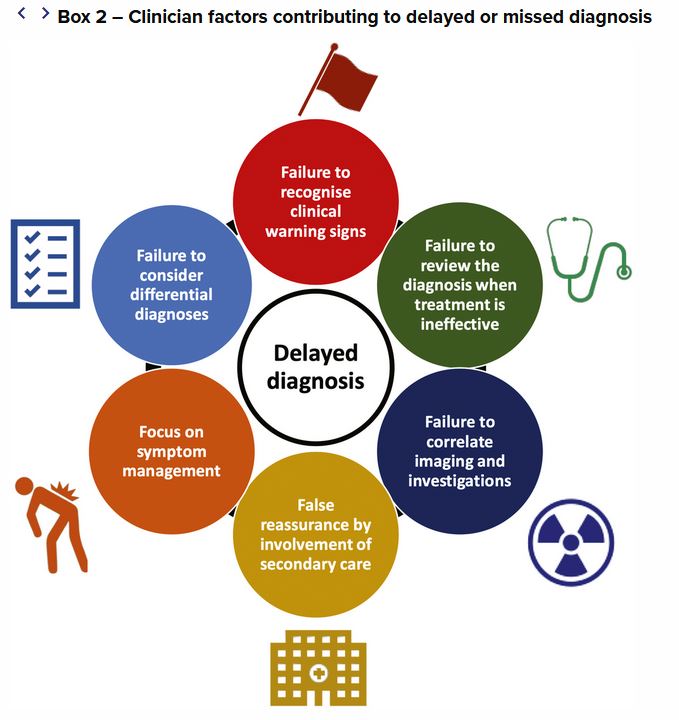

A number of clinician factors contributed to missed or delayed diagnosis (Box 2).

Failure to notice clinical warning signs. With the benefit of hindsight, warning signs were often missed at some point during the patient’s consultations. However, the individual GP was often one of between five and 15 different GPs who had seen the patient with a similar presenting complaint. The same benign pathology had been ascribed to the presenting complaint many times before, suggesting that the power of thought anchoring was likely to be strong, and the warning signs were missed when they appeared.

Failure to reassess diagnosis when treatment was not effective. Persistence with the same diagnosis and same mode of treatment, in the absence of any improvement in signs or symptoms, was a common feature; for example, a persistent chronic cough still considered infectious after months of antibiotic therapy. This represented “premature closure” — the failure to consider other possibilities once an initial diagnosis has been reached, which is one of the most common cognitive causes of diagnostic error. Fragmentation may amplify the risk of premature closure, if one GP among many does not perceive that it is their responsibility to re‐open the differential diagnosis. Notably lacking from the medical records in our cases was a list of differential diagnoses, despite research suggesting that failure to document a differential diagnosis in the primary care setting is associated with missed diagnoses.

Focus on treating the presenting symptom. Pain, often chronic, was a frequent presenting symptom. A good example is severe back pain, thought to be musculoskeletal, where the consultations focus on pain management and not the underlying diagnosis.

False reassurance derived from involvement of secondary care. There was a recurrent theme that once the patient had been seen in secondary level care, including emergency, there was an assumption by the primary care doctor that a thorough work‐up had excluded serious pathology. In reality, this was often not the case.

Failure to acknowledge results of tests or investigations. Of concern, there were several examples where imaging or investigations had been appropriately ordered by a GP and explicitly reported as concerning for serious pathology. However, the reviewing GP was often not the requesting GP, and these reports failed to make their way into the diagnostic processes of the treating doctors.

Inappropriate prescribing

Inappropriate prescribing, especially of opioids, comprises one in 20 claims made to Avant Mutual. Our review identified a number of cases where multiple GPs were involved in prescribing medications, and where prescribing failed to comply with state prescribing legislation and compromised patient safety. In some situations, high risk medications were prescribed to the same patient by more than 10 different GPs across multiple practices. With no single GP assuming full responsibility for the patient, it appeared that each individual GP assumed a pattern whereby medications were prescribed based on previous prescribing behaviours.

Failure of preventive medicine

In some compensation claims, allegations of negligence involved failure to address modifiable risk factors of disease. Examples included failing to manage high cholesterol levels and hypertension, to mitigate the future risk of vascular disease. It is unsurprising that management of these risk factors — which require patient engagement and motivation, regular follow‐up, careful liaison with specialists, and titration of medication over time — was impacted by fragmented care.

Discussion

Because we searched the case file database for cases involving fragmented care and adverse outcomes, we cannot draw any conclusions on causality. However, in this highly selected case series we had a unique opportunity to examine where failures and contributing factors were analysed by medical experts, legal experts, regulatory bodies and coronial inquests.

Throughout these cases, there was a recurring theme of individual GPs believing they were not the primary care provider. Many GPs incorrectly considered that, while they had a duty of care in relation to the presenting complaint during one particular consultation, they were not responsible for taking care of all issues in the patient’s background. There was a range of outcomes for the doctors involved, including regulatory action, adverse comment by coroners and medical regulators, and compensation payments by the doctor’s insurer.

Each doctor has a duty to exercise reasonable care and skill in treating patients (Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58). This extends to examination, diagnosis and treatment, and providing information. A GP will breach their duty of care if they do not act in accordance with the standard of care expected of a reasonable GP in the same circumstances.

What a doctor must do to fulfil their duty of care will differ depending on each patient’s circumstances, including the presenting problem, history, and the potential harm that might result from inappropriate care. Whether or not the patient sees another doctor does not matter. A GP has a duty independent of any other practitioner and it is not a defence to say “they were not my patient” or “I was not their usual doctor”.

Although it is difficult in busy real-world practice, doctors need to be alert to the risks of fragmented care, acknowledging that health care homes and patient enrolment are not currently the established model of general practice in Australia. Simple strategies can minimise the risk of adverse outcomes:

- Reviewing and recording the patient’s reason for the visit, reading through the records of recent consultations, and reviewing the patient’s health summary for important historical background.

- Reviewing important previous investigations, even if they were ordered by a different practitioner. In some cases, My Health Record may shed light on previous conditions and investigations.

- Explicitly asking patients if they have seen other clinicians for their current health problems.

- Advising the patient of the importance of following up the results of investigations and referrals.

- Being aware of anchoring bias, and a need for critical appraisal of previous assumptions, which may stave off delayed diagnoses.

- Attempting to ensure that appointment allocation within a practice is to the same doctor each visit where possible.

As we move into a new era of telehealth, mechanisms to limit unrestrained fluidity of primary care — such as the current temporary Medicare Benefits Schedule telehealth requirement to have seen a patient face‐to‐face in the previous 12 months — will become important (notwithstanding the acknowledged limitations of telehealth).

Conclusion

Our findings identified three key areas in which fragmented care was associated with adverse outcomes or a greater risk of patient harm: diagnostic error, poor prescribing practices, and deficits of preventive medicine. An awareness of risk mitigation strategies is essential to ensure that the negative outcomes of fragmented care are limited.

Dr Jack Marjot is an emergency advanced trainee and Medical Advisor at Avant Mutual.

Georgie Haysom is Head of Research, Education and Advocacy at Avant Mutual.

Dr Penny Browne is Chief Medical Officer at Avant Mutual.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

This occurs when

– you only pay GPs for a 15 min consult as a standard- decisions need to be made using heuristics, on the fly or with full bladders, empty stomachs to maintain income

– the patient is difficult with multiple complex co morbidities

– the patient is manipulative/drug addict not wanting to use non opiods treatment as too much hard work for them

– the patients always wants 2-3 things addressed in a consult but cant be bothered booking in longer consults because they think medicine is easy , the doctor doesn’t fatigue and apparently medicine doesn’t require prolonged concentration 7 days a week

– Patients in the wait room doesn’t want to wait 2 hrs as the GP runs late as they gp comprehensive workup on each and every patient day in and day out

– poor software means consult times are spent clicking / filling/unfilling irrelevant areas on the computer and the GP has to search through a mountain of material to just get a summary of information -look at HPOS system-a new layer of passwords etc to get info and my Health record that is unusable in real time unless you are in ED and 2-4 hrs to work up a patient

– GP does 7,000 clicks a day entering non important information= wrist hand eye fatigue and info overload

What could go wrong?

Perhaps we should be like the legal system which takes months to make a ruling on a condition – less opportunity for errors then.

Who could not see this coming? After the years of wholesale expectation by patients of universal bulk billing , with the associated market pressure on GPs to have to participate, and the rise of corporate practices, has seen a largely part time , contracted work force, with no sense of practice ownership, which too easily translates into the “ fragmentation” of care, as described. Nothing incentivises like being personally financially responsible for one’s own practice, the “ success “ of which once followed individual dedicated “ continuity of care “, which , in turn, encouraged a loyal “ following” and resulted in a valuable “ good will “ to sell at the end of a justly proud working life. A “ win win” outcome. This was hard to put into words , but I think of us who agree, have also retired.

Is anyone courageous enough to analyse the data in terms of the causes behind WHY doctors can’t voice the time to continuity of care? Like, is it more likely in younger vs older, ethnic group vs ethnic group, female vs male, practise ownership vs corporate practice?? Or are we reluctant to face truth . . . ?

Fragmented care is a form of ‘patient abandonment’. It is like a symphony orchestra with no conductor. It is costly to the patient and to Medicare and is bad medicine. It makes a joke of our constant claim that we have the best health care in the world. Those who are fortunate enough to have a GP who knows them and who looks at them when they walk in and who examines them and follows up on previous complaints or conditions are fortunate indeed.

The causes are obvious but the solutions elusive.

The corporatisation of general practice and the prevalence of the “six minute” appointment. The failure of doctors to listen to or do even a basic physical examination of patients. Staring at a computer screen and simultaneously typing prescriptions and/or referrals whilst “consulting”.

During the last 9 months I have had CABG and spent a total of three months in hospital with both heart and renal failure, so speak from some experience. And I am a retired medical specialist, so what is Joe Public putting up with?

Applies equally to secondary/tertiary care – different doctors each time, no one taking ownership. Some of this applies more in public hospitals, but can be the case with patient seeing (too) many different specialists