THE COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it an unprecedented demand for timely and rigorously developed evidence. Decision makers in clinical, managerial and policy roles have sought and needed information and insights to help them address complex and rapidly evolving challenges, in a context of significant uncertainty and rapidly evolving evidence.

Australian clinicians have a long history of translating evidence into practice (here, and here), but most will acknowledge that translation of evidence into clinical practice is usually protracted and that there is rarely a straight line between evidence and action.

Many clinicians have contributed to a shift in the translation paradigm in the context of COVID-19 – with significant practice change enacted rapidly – and have called for Australia to retain and strengthen what’s worked during the pandemic as the foundation for an emerging national evidence ecosystem.

A coordinated national effort with strong ownership and engagement of clinicians in the production and the use of evidence – particularly in clinical guidelines – has been key. Coordination by the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce enabled the production of a unified set of rapidly evolving (“living”) national guidelines applicable across diverse contexts and sectors.

The Taskforce produces high quality syntheses of the evidence and national clinical care recommendations, supported by strong clinical and stakeholder engagement, on a range of topics related to the treatment and care of people with COVID-19.

These national efforts link with evidence systems at a state level. For example, NSW Health established a Critical Intelligence Unit (CIU) at the start of the pandemic, bringing together clinical, research and policy experts to advise decision makers across the health care system and government more broadly.

The CIU complements and builds on national guidelines by scanning published literature, analysing local data, and conducting surveys to assess the experiential evidence emerging from real clinical and community settings. It catalyses international and local discussions in areas where these sources remain inconclusive or insufficient to guide decisions.

In Australia and internationally, gains made in the response to COVID-19 in terms of evidence generation and synthesis; knowledge distribution to support timely clinical, policy and managerial decision-making; and collaborative approaches to data sharing, analysis and modelling (here, here, and here) mean we now have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to shift the way we generate, disseminate, synthesise, use and communicate evidence.

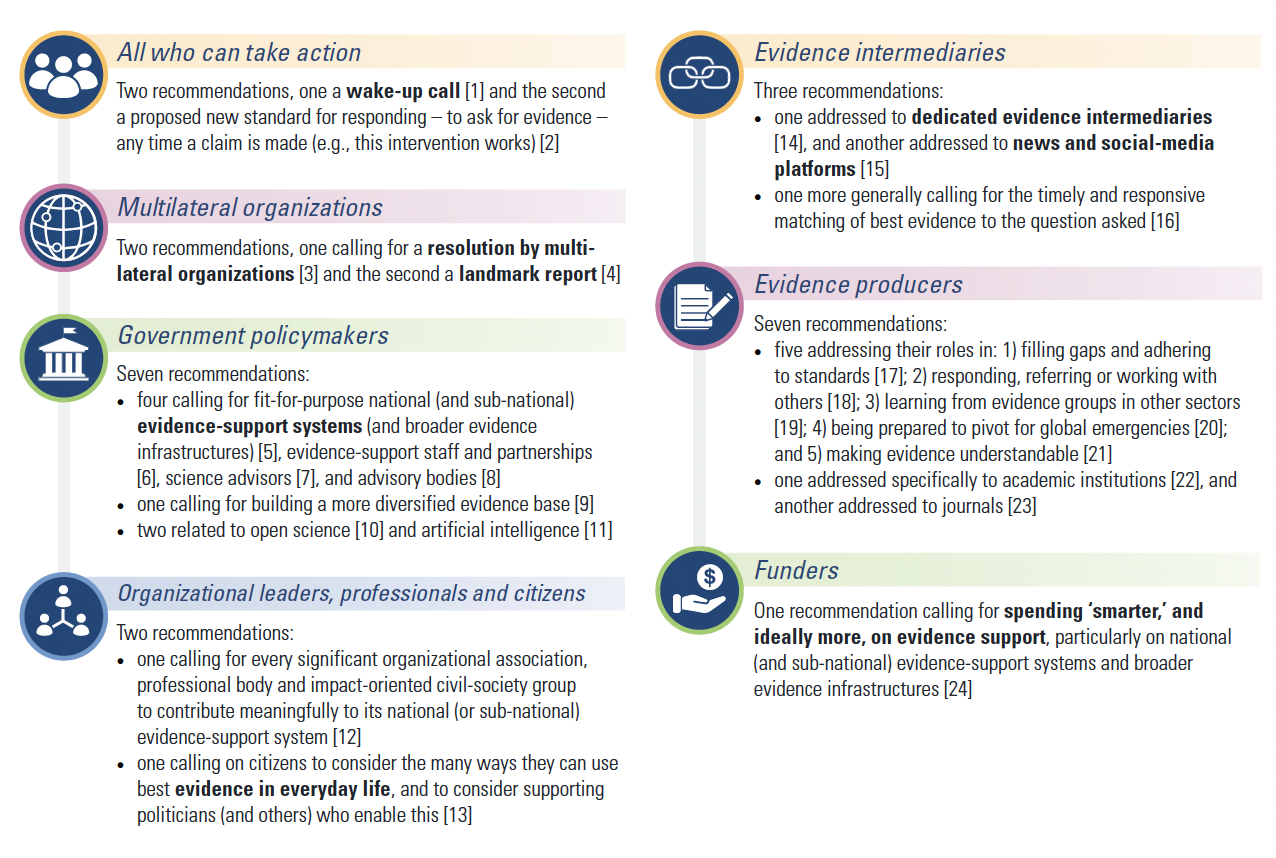

This opportunity has been highlighted by the release on 27 January this year of the final report of the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges. The report sets out an ambitious agenda for reshaping the evidence ecosystem, building on what has been learnt during the pandemic. The Commission makes 24 recommendations for society to grasp this opportunity (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overview of recommendations by the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges

The report describes key facets of the evidence ecosystem, including:

- different types of decision makers – policy makers, organisational leaders, professionals and citizens;

- a range of geographical and sectoral efforts and responsibilities – at global, national and local levels;

- different types of evidence – spanning data analysis, research, and experiential evidence focused on a broad range of subject areas including behavioural science, implementation research, technology assessment, modelling science and evaluation; and

- the complexity of the underlying problem – simple, complicated, complex and complexity cubed (sometimes referred to as “wicked”).

Key recommendations from the Commission include:

- a formal resolution from the United Nations, G20 and other international bodies, committing them to better use of evidence;

- a World Bank World Development Report dedicated to evidence;

- a review among governments of all levels as to how they use evidence – including how they evaluate their programs; and

- initiatives to support better use of evidence by citizens, such as in combating misinformation, and making everyday decisions.

The Commission’s report resonates with our pandemic experience in Australia from system and clinician perspectives. Our experience has shown that evidence can help to bring clinicians, health managers and policy makers to mutual understanding, and help resolve complex problems affecting the health care system. Decision making can be rapid, responsive and iterative when information and sound advice is available. When debates about what works can be settled quickly, efforts can be oriented towards action.

The distinction made by the Commission report about national and local roles and responsibilities is emerging as critically important. Research evidence is often widely applicable and can be synthesised and applied at international and national levels, but important knowledge often emerges out of the application of this evidence, adding localised and contextualised information. Here the clinician voice is essential – knowing what and how to apply new knowledge.

A key element of success identified both in the Australian context and in the Commission’s report is the value of intermediaries in the evidence ecosystem. Intermediaries, sometimes called versatilists, are experts who are skilled at engaging with a wide scope of situations and problems, with integrative capacity across disciplines and contexts. They enable and encourage triangulation, critical review, and cross boundary thinking – spanning conceptual, organisational and geographical divides.

Similarly, intermediary organisations have a critically important role to play in evidence ecosystems, ensuring that evidence-based policy and practice is promoted and supported, taking into account diverse stakeholder perspectives, clinical and health system organisation imperatives, and consumer and population health viewpoints. Such boundary spanning allows us to go beyond single studies and undertake systematic and deliberative processes to summarise available evidence from a plethora of single, often contradictory, studies.

The pandemic has emphasised the need for such processes and the feasibility and benefits of rapidly and repeatedly updating evidence summaries and guidance using a living evidence model. This approach was originally developed in Australia and is now being taken up around the world, including by the World Health Organization and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

The international movement outlined in the Commission’s report will help to build a new evidence ecosystem that integrates up-to-date, rigorous evidence synthesis, expert opinion, and patient perspectives. Australia has established some foundations for a modern, fit-for-purpose evidence ecosystem, but the systems and structures required to support evidence-based policy and practice have not been established consistently across the country or across different disease conditions.

In our response to COVID-19, we have glimpsed the promise offered by a more integrated and responsive evidence ecosystem in Australia – and the considerable benefits that would bring for practising health care professionals.

Rapid, living and rigorous evidence review and guidelines – for example, national appraisal and advice, and state-based model of care for the use of monoclonal antibodies in COVID-19 – reduces uncertainty and provides reassurance that the most up-to-date living guidance is freely available. Evidence systems at state and local levels support their translation into clinical models, grappling with the complexity of implementation and rapidly evolving local contexts to enable rapid and frequent review of models of care.

A pandemic is an extraordinary situation and COVID-19 has prompted the rapid evolution of evidence systems in Australia, both nationally and at the state level. The persistence of these advances beyond the pandemic will require a collective commitment to effective evidence models and systems.

Dr Kim Sutherland is the Director, Evidence at the NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation and leads the analytic teams of the NSW Health COVID-19 Critical Intelligence Unit.

Dr Jean-Frederic Levesque is the Chief Executive of the NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation and the Executive Lead of the NSW Health COVID-19 Critical Intelligence Unit.

Associate Professor Steve McGloughlin is an intensive care physician and infectious diseases physician, director of the The Alfred Hospital ICU, a 56-bed quaternary intensive care unit, and Executive Director of the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce.

Professor Julian Elliott developed the Living Evidence model and established the Australian Living Evidence Consortium and National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce, both based at Cochrane Australia, Monash University, and is CEO of Covidence.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert