CONGENITAL cytomegalovirus (cCMV) infection is the most common, and potentially preventable, infectious cause of permanent hearing loss and child neurodevelopmental disabilities such as cerebral palsy. Approximately 400 infants in Australia are either born with or develop cCMV-related issues in Australia per year.

The most common sequelae of cCMV are sensorineural (permanent) hearing loss affecting around 13% of infants, vision loss, cerebral palsy, intellectual impairment and neurodevelopmental disability (here, here and here). Despite this, the public, and even health professionals, have little awareness of cCMV. There is no effective vaccine for the prevention of cCMV infection. While there has been a shift in the understanding of viruses and infection prevention and control, adequate infection prevention of CMV for expecting mothers is low (here and here). As Professor Demmler-Harrison accurately states, it is “the elephant in our living room”.

CMV is a virus in the herpesvirus family. Once a person is infected, the virus remains viable but usually inactive (dormant/latent) in the body. The infection is common but silent, affecting around 83% of adults, with most remaining asymptomatic. CMV is generally spread by direct contact through bodily fluids such as saliva, nasal mucous, or urine, for example, through kissing children on the lips, sharing food, handling children’s toys or changing nappies without washing hands.

CMV can be problematic for pregnant women if caught for the first time (primary infection) or reactivated from its latent state. The most risk of transmission to an unborn baby is when CMV primary infection occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy of a non-immune mother. A minority of babies born with cCMV infection can be unwell at birth, but most (about 90%) are born without any clinically apparent symptoms (here and here). Of these initially asymptomatic infants, around 14% go on to develop hearing loss or neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Worldwide race to implement early cCMV screening

Research in 2015 demonstrated prolonged (6-month) antiviral medication with oral valganciclovir, if commenced within the first month of life for babies with symptoms from cCMV infection as newborns, resulted in improved hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes in many infants beyond a year of life. However, as this study only enrolled symptomatic infants, we do not yet know whether antiviral medication benefits cCMV-infected newborns who have isolated hearing loss or no symptoms at birth. Further research is needed to clarify this. The International Congenital Cytomegalovirus Recommendations Group in 2015 recommended that infants who are moderately to severely affected by cCMV be offered oral valganciclovir for management, and it is not currently recommended as routine practice for infants with isolated sensorineural hearing loss or mild symptoms. A case-by-case discussion between families and clinicians is required in these instances and the decision whether to commence treatment is dependent on when the diagnosis occurs and the severity of hearing loss or neurodisability, in order to weigh up potential benefits and side effects such as neutropenia.

The potential effectiveness of early antiviral therapy in reducing cCMV-related hearing loss progression and neurodevelopmental disabilities has led to a worldwide push to implement early screening for cCMV. To accurately diagnose cCMV infection, urine or saliva samples must be taken from the newborn within the first 21 days of life, because samples taken after that time period may indicate post-natal CMV infection, which does not cause hearing loss or neurodisability. International consensus guidelines recommend a targeted cCMV screening approach for newborns who do not pass their universal newborn hearing screen by saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Studies in the UK (here and here), the US and Israel have demonstrated targeted cCMV PCR screening to be feasible when saliva swabs are taken in the hospital before newborns are discharged. Some states in the US have mandated targeted cCMV screening (here and here).

Further research currently underway looking at the potential benefit versus risks of antiviral treatment for asymptomatic or mildly affected infants, is important in understanding whether universal screening is an option for identifying cCMV positive infants.

Targeted cCMV screening in Australia

Currently, there is no routine nationwide newborn screening for cCMV in Australia. Targeted cCMV screening was piloted in Queensland, and was feasible and cost-effective when completed by hearing screeners before newborns were discharged from hospital. Another pilot study to evaluate targeted cCMV screening is underway in Western Australia and results are expected to be available in the next few years. However, with the trend towards early discharge of postpartum mothers from hospital, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need to test other ways of targeted cCMV screening to avoid missing cCMV infection in newborns who are rapidly discharged home.

Our study, published in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, aimed to test the feasibility and acceptability of targeted cCMV PCR screening by parents themselves taking saliva swabs from their newborns through the Victorian Infant Hearing Screening Program (VIHSP) at the four largest maternity hospitals in Victoria. Parents completed the saliva swab at the time their newborn did not pass VIHSP’s hearing screen, either in hospital or at home, and sent the saliva samples to a central pathology laboratory through the post or through hospital services, depending on where the swab was completed.

Our work demonstrated the parent-conducted targeted cCMV screening program to be feasible, with 76% of families agreeing to participate and 100% of the 96 swabs completed within the required time frame of 21 days from birth. One infant was confirmed to have cCMV infection and was able to immediately see an infectious disease clinician to discuss the option of antiviral therapy. We also captured the parents’ perspectives of the program. The majority of families (over 90%) found the screen was easy to do, thought it was a good idea, and were glad their baby was screened for cCMV.

We have therefore demonstrated a new way of targeted cCMV saliva PCR screening to detect cases of cCMV infection that might be otherwise missed by early hospital discharge, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesise this targeted cCMV screening approach can be successfully implemented statewide with the addition of training of hearing screeners, midwives and nurses to complete saliva swabs in hospital before discharge, to increase uptake and reduce the potential for false positive results.

How about universal cCMV screening?

Before thinking about universal cCMV screening in Australia, we need to understand how common cCMV infection is in newborns in Australia, and we also need to develop cheaper, more convenient and more rapid ways to screen for cCMV to enable implementation at a population level. We also need more data on whether antiviral treatment is beneficial for newborns with cCMV infection who are asymptomatic or have isolated hearing loss.

A recent grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) will allow our research team to use data from the Generation Victoria research project to determine how common cCMV is in a 2-year birth cohort of more than 110 000 newborns in Victoria. We will partner with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research to develop a rapid bedside screening test for cCMV. Our research team is also involved in running the Australasian Congenital Cytomegalovirus Register, an Australian and New Zealand registry administered by the Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Institute at the University of Sydney. The registry, which commenced in 2020, aims to track the outcomes of children with cCMV and understand the effects of antiviral therapy on neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with cCMV infection.

Conclusion

Overall, things are heading in the right direction in the early detection and clinical management of cCMV infection in Australian infants and children. However, there is room for much more to be done in terms of raising awareness of CMV in pregnancy to ultimately prevent cCMV infection, which is the leading infectious cause of hearing loss and neurodisability in children, and to adequately address the “elephant in the living room”.

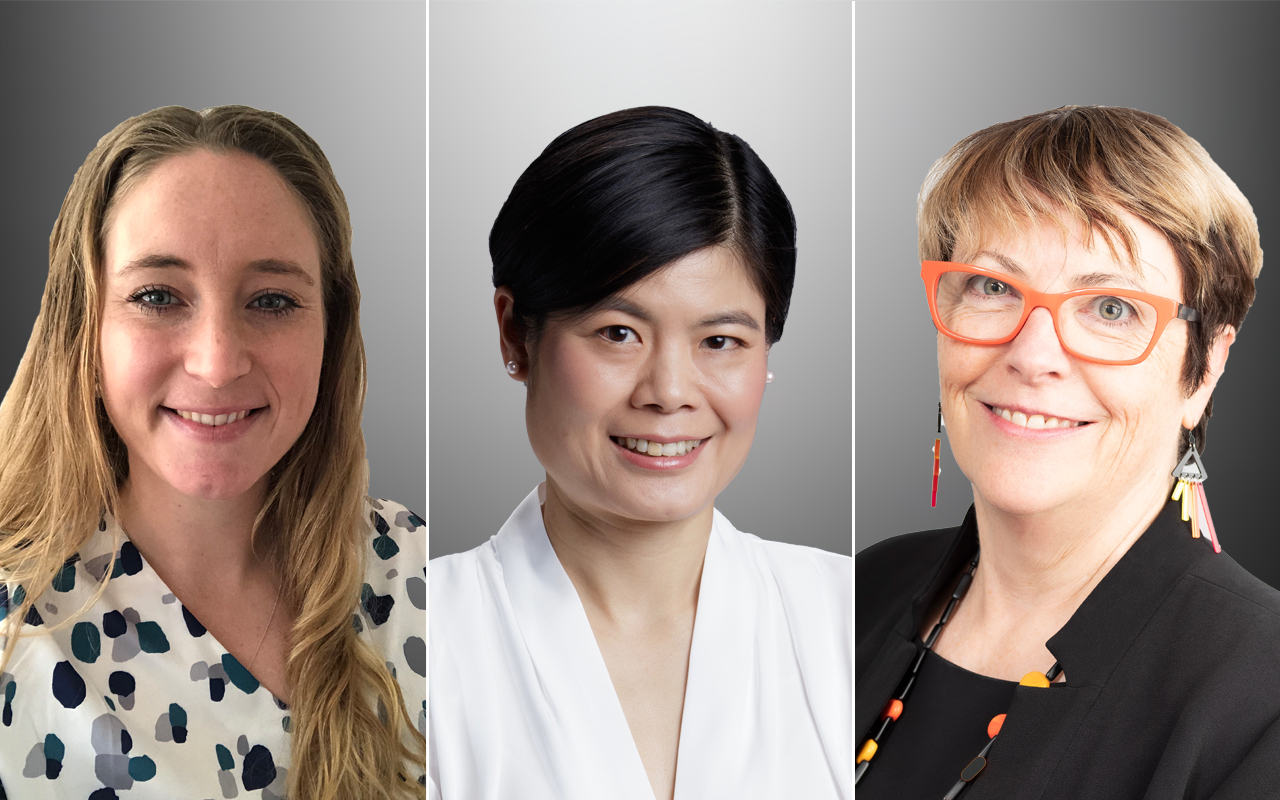

Emma Webb is completing her PhD at the University of Melbourne, looking at understanding factors facilitating early screening for congenital cytomegalovirus in infants. Emma is a clinical audiologist by background working in the diagnostic space.

Valerie Sung is a paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Clinician Scientist Fellow and Team Leader at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and Honorary Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne.

Professor Cheryl Jones is a staff specialist in infectious diseases, Dean/ Head of School of Sydney Medical School and a world authority on congenital infections.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

I would like to make a donation to CMV research. Can you please advise where / to whom I should donate.

My son (recently turned 3) was asymptomatic at birth and commenced valgancyclovir at 5 days old, administered for 6 months. So far his sensorinueral hearing loss in his left ear has been his only diagnosis from the silent virus. He has a cochlear implant. I have recently filled out a questionnaire for the Australasian Congenital Cytomegalovirus Register, but more than happy to answer any more questions to assist in research!

As a mother of a CMV daughter, I am definitely in favor!

Very good project . Unbelievable that there is so little public awareness of this horrid infection.