DIGITAL health has been heralded for many years as an excellent means to extend health services in mental health.

Nearly a year ago, we wrote that COVID-19 offered the opportunity for transformational change in the use of digital health and telehealth by improving access and quality of health care. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a ramping up of new digital measures, including extensions of crisis lines, new COVID-19-specific call lines, and the introduction of Medicare-funded telehealth for mental health services. We also saw development of innovative services such as The Essential Network (TEN) service designed to provide support to frontline workers. Following this, the Productivity Commission, the Victorian Royal Commission and the National Suicide Prevention Advisor reports made recommendations about digital reform.

The COVID-19 measures that were introduced in 2020 increased the volume of services available to the community. It appears that demand for these services has increased. A measure of activity is a relatively weak measure of success. It is not yet known if those who visited these services were new patients. It is unclear whether the call centres reduced psychological distress at an individual level, or whether the same levels of distress would be recorded if these services had not been introduced. It is not clear whether they were successful in diverting people in distress from treatment services or that they improved the efficiency of the health services.

Mental health service use data from Lifeline and Beyond Blue and our own web traffic from the Black Dog Institute suggest that call centres and websites experienced increased usage of approximately 15–30% in response to COVID-19. These calls and web traffic continued at a higher than baseline rate for all services and taper and expand in response to lockdowns (here and here). For example, Lifeline is experiencing a 25% increase in the volume of calls Australia-wide since the surge in new COVID-19 cases began this July. a significant increase from pre-COVID-19 levels of approximately 2500 per month, and has again reported an increase in calls in response to the July 2021 lockdowns.

The analysis of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) billing data suggests that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an overall increase in the level of psychiatric service (telehealth and face to face combined) compared with the previous year (here and here). During the first peak of COVID-19 (April–May 2020), about 50% of mental health consultations occurred via telehealth. Although proportional telehealth use has dropped now with around 20% of total mental health consults occurring via telehealth, it is likely that telehealth will “stick” as the preferred medium for select groups, with usage rates remaining higher than before the pandemic.

However, neither the recent measures nor the recommendations from the Productivity Commission, the Victorian Royal Commission and the National Suicide Prevention Advisor provide the broad framework we need in Australia to advance digital mental health technologies. This is particularly concerning because the government’s Digital Transformation Strategy 2018–2025 aims to deliver world-leading digital services to the community with the aim of being one of the “top three digital governments in the world”. Government rhetoric and government action are not yet aligned.

Despite Australia’s aspirations to become a digital leader, both the measures initiated through the COVID-19 pandemic and the recommendations of the three major reviews do not provide the transformative framework we need to reach digital success in mental health. Except for the TEN service and other third generation digital systems such as Orygen’s Moderated Online Social Therapy, the COVID-19 digital services were essentially “more of the same” – increasing the volume of services, but not changing the nature of service provision in line with the potential scalability and efficiency of digital services. Within Australia there is already a mismatch between mental health service activity and need, with the least service activity in the areas that are likely to be most in need. Simple increases in the provision of digital products may not result in the digital products being deployed where they are most needed.

In short, while the Productivity Commission and other reports address important components of a digital framework, these reviews do not tackle structural issues.

We have yet to hear about the elucidation of a pathway or a service model for the many circumstances that will attract people to this portal. Moreover, it is unclear where the referral information will be kept, although, it is suggested that, in the future, the consumer could hold this in My Health Record and determine for themselves with which service providers they should connect, placing increased onus on the consumer. If technology can solve the interconnectivity around this problem in other disciplines, one wonders why a new digital platform could not do that in 2021. The three reports are also silent on commercial digital services provided by online health providers or start-ups which aim for more comprehensive models. Ignoring these is likely to stifle innovation and perpetuate health inequity into the future.

One of the ways in which digital therapies can be used is using blended care models, where some of the treatment is therapist-led and some of it is self-managed by the patient using evidenced-based digital therapies. The Productivity Commission agrees that blended therapy is efficacious and cost-effective. However, the availability of online blended services such as MindSpot and THIS WAY UP is predetermined by the “fixed capped” funding provided by government, preventing these services from growing or scaling unless they become privatised and require consumers to pay.

Here, there is a risk that subsidies are not well targeted and may not reach the most vulnerable who do not have the ability to pay for the services they need. The Productivity Commission essentially concludes that a slow roll-out of blended services is needed to ensure quality, and recommends ongoing reliance on grant funding to continue investigation. This cautious approach does not encourage innovation or offer a future-focused solution.

What would an integrated digital mental health system look like?

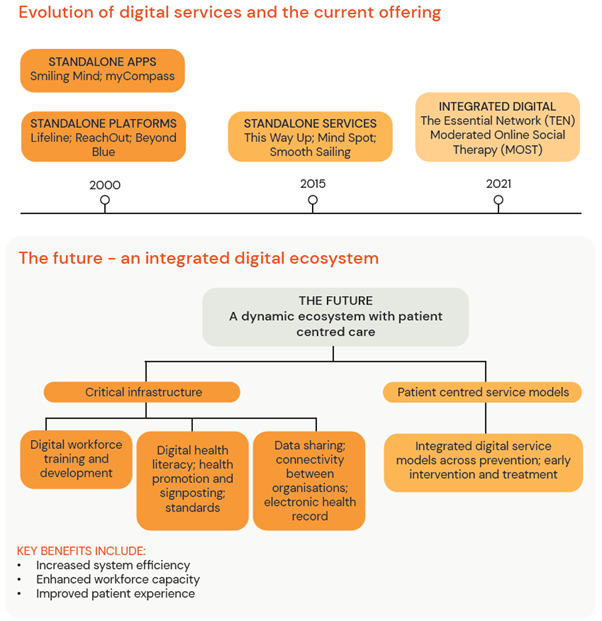

Successful mental health system reform will require the integration of existing digitally enabled services into a networked “digital ecosystem” that is connected in to face-to-face care (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A model of an integrated digital ecosystem for mental health services

An ecosystem could be a more sophisticated version of the digital Head to Health platform that fully integrates with MBS data monitoring and analytics, My Health Record, and other health and social service systems. The ecosystem would provide a clear entry point to services and touchpoints, while providing a platform to monitor patient outcomes and tailoring dependent on patient progress.

We propose that a framework would start with the patient-centred service models that need to be developed to support integrated digital models. For example, we would aim to amplify digital therapies in general practice to create more efficient treatment and better collaborative care for common mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. There is ample evidence from Europe and the US that collaborative care models improve outcomes for patients with depression. What is less clear is how these models can be adapted for the Australian health care system and the role that technology can play in making these models of care more effective and efficient.

The plan would be to negotiate with organisations so that they create a collaborative care environment for the patient – a patient-centred model that is supported by a dynamic ecosystem of organisations. This requires education for users and service providers and the establishment of working arrangements with organisations that currently provide certain aspects of care. Governments must build the IT systems and regulatory frameworks that allow connectivity in this new ecosystem (not platforms ahead of the requirements of the ecosystem) and the regulation for health record data to be shared seamlessly.

For an integrated ecosystem to be effective, appropriate incentives should be provided through the MBS, regulatory frameworks, and grant programs to accelerate the technology behind new services and to increase uptake of the new service models by both clinicians and consumers. Evaluation and monitoring of these new digital and blended services will be critical, yet policy should be flexible enough to allow for ongoing innovation and technological change.

What is needed now?

We are unclear of the government’s plans for digital services beyond the “announceables” and early discussions around a potential National Digital Mental Health Framework. We believe there is an urgent need to develop a comprehensive policy framework in the first place with the sector to guide investment and regulation, much like the ecosystem model we suggest above, to truly deliver quality digital services to consumers and patients. We already have examples of potential systems that are working, such as the TEN service, This Way Up, and MOST.

Using these dynamic models will improve digital mental health delivery, but there needs to be clear government strategy and policy to enable these innovations to meaningfully integrate with the mental health system. Otherwise, Australia will fall behind international best practice for patient-centred mental health care delivery. Without a change in our trajectory, we will fail to realise the potential efficiencies digital technology presents for the mental health system and the potential improvements for individuals seeking help.

Professor Helen Christensen AO is the Chief Scientist at the Black Dog Institute and Scientia Professor of Mental Health at UNSW Sydney.

Dr Natalie Reily is a Research and Policy Officer at the Black Dog Institute.

Caitlin Connell is the Government and Stakeholder Relations Advisor at the Black Dog Institute.

Dunkan Yip is the Policy and Strategy Advisor at the Black Dog Institute.

Professor Sam Harvey is the Chief Psychiatrist and Acting Director of the Black Dog Institute.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

A very thoughtful and balanced analysis. As someone specialising in the management of dementia in all settings working in rural and remote South Australia, I have been alarmed by the extent that Telemed has become the main service delivery model for the Mental Health Services for Older Persons, even when what constitutes “rural” is a short distance away. The TV environment is far from comfortable for people of the generations that need these services, and an audience at each end is not accepting the individual’s right to a confidential one-on-one consultation. When we are dealing with behavioural issues in residential care understanding the actual situation in that individual’s case is critically important and cannot be left to proxies.

I believe from hard experience that an initial assessment based on the biopsychosocial model can not be achieved by this means. Access to psychotherapy is very difficult at present. In any psychiatric condition commonly seen in “the elderly” (a much discriminated against minority group) psychotherapy is an integral part of a management plan which should be routinely available through an integrated system.

Having got past this hurdle access to any form of psychotherapy is through the internet. This