BARIATRIC endoscopic procedures, including intragastric balloons, potentially fill the gap between severely obese patients for whom the increased risks of laparoscopic surgeries are justified, and those who would benefit from weight loss surgery with lower risk profiles.

A narrative review published by the MJA concluded that the field of bariatric endoscopy “appears to have matured to a critical point in its development”.

“These myriad of techniques appear safe and effective and greatly expand the therapeutic arsenal available to patients with excess weight, providing the next major breakthrough in the management of obesity,” wrote the authors, led by Dr Dominic Staudenmann from the AW Morrow Gastroenterology and Liver Centre at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

“In general terms, endoscopic bariatric therapies offer average total weight loss of between 10% and 20% and results are generally augmented by providing multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention”, the authors wrote. “As such, endoscopic bariatric therapies should be considered adjuncts to lifestyle intervention rather than as a replacement for them.”

Dr Adrian Sartoretto, a co-author of the review, told InSight+ in an exclusive podcast, that bariatric endoscopy catered to a “middle range” of patients with obesity.

“For a very long time, we had [weight loss] medications that were relatively safe, but also relatively ineffective,” said Dr Sartoretto, a gastroenterologist and bariatric endoscopist with The BMI Clinic.

“Then the next step up from that was surgery, where, even though the surgical risk was worth the benefit in so far as mortality [and complications], it was still a substantial increase in risk, and a huge increase in efficacy.

“But there was a middle range where people wanted a lower risk, maybe a less efficacious procedure, but without the risk attached. That’s where bariatric endoscopy sits.”

Two endoscopic procedures are most often performed by bariatric endoscopists.

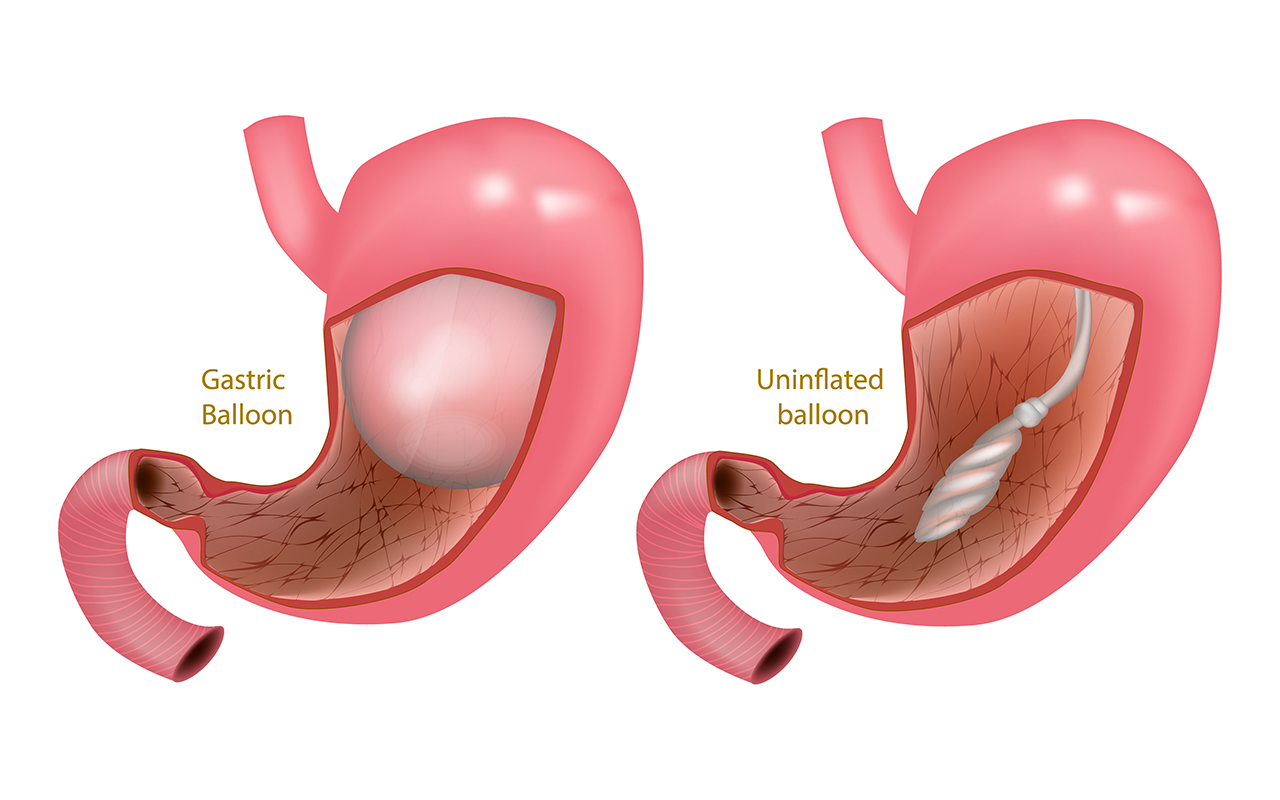

“The most well established endoscopic bariatric therapy is the intragastric balloon — a non‐surgical approach to weight loss,” wrote Staudenmann and colleagues.

“It is a space‐occupying device that is placed in the stomach, leading to an early feeling of satiety and delaying gastric emptying.

“A meta‐analysis of [randomised controlled trials (RCTs)] showed a significant improvement in most metabolic parameters (fasting glucose, glycated haemoglobin [HbA1c] level, blood pressure, waist circumference) following intragastric balloon compared with controls.

“Fluid‐filled intragastric balloons are marked by an adaptation period of 3–5 days, during which time patients may experience abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, reflux or regurgitation, and bloating.

“Device‐related complications occur infrequently and include spontaneous hyperinflation, gastric outlet obstruction, gastric ulceration and perforation. Although the risk of perforation is low, proton pump inhibitors for the duration of the intragastric balloon therapy and Helicobacter pylori eradication are important for ulcer prevention following intragastric balloon deployment.”

The second procedure is an endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty.

“The endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a novel, transoral procedure to reduce gastric capacity and delay gastric emptying by way of full thickness suturing along the greater curvature of the stomach,” wrote Staudenmann and colleagues.

“This procedure has been facilitated by the development of a cap‐based endoscopic suturing device. The endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is performed under general anaesthesia and is frequently a day procedure, with full patient recovery after 3 days following intervention.

“Data from multiple centres indicate a weight loss of about 15% at 6 months and 20% at 18 months. Moreover, early data suggest that this procedure results in significant improvements in markers of metabolic syndrome (HbA1c level, systolic blood pressure, waist circumference, alanine aminotransferase, and serum triglycerides).

“Major complications are experienced by about 1% of patients, which include perigastric inflammatory collections, major bleeding and deep vein thrombosis.”

Dr Sartoretto told InSight+ that bariatric endoscopy was a less resource-intensive alternative to laparoscopic bariatric surgery.

“At the moment, there are something like 7 million obese Australian adults,” he said.

“Surgery is a very resource-intensive way of addressing that, [requiring] hospital admissions and occasionally [intensive care unit] admissions.

“Bariatric endoscopy is generally a day only procedure, and people recover in a fraction of the time of the surgical equivalent.

“From a resource perspective it’s a better fit for the scalability of meeting the nature of the problem we’re dealing with.”

Although bariatric endoscopy is a cheaper procedure than laparoscopic bariatric surgery, unlike surgery, it is not covered by private health insurance, and therefore ends up being more expensive for patients.

Dr Sartoretto told InSight+ that both the obesity and diabetes epidemics as well as the evidence base for bariatric endoscopy were reaching tipping points.

“We’ve now got the RCT data to support [bariatric endoscopy],” he said, “so subsidisation is something that really needs to be considered.”

Bariatric endoscopy is not suitable for every patient with obesity, however.

“First of all, we know that risks of major complications are much higher once you get over 70 years of age,” said Dr Sartoretto.

“There’s a bit of a gray area between 65 and 70, so you want to think long and hard before putting a balloon in a patient like that.

“Anyone who’s had any form of gastric surgery, those patients are very high risk as well, and obviously anyone on obligate blood thinners – anticoagulants, antithrombotics or obligate anti-inflammatories – because anti-inflammatories and gastric balloons don’t mix. Obviously, we’ve got a foreign body sitting within the stomach that might induce microtrauma on the gastric lining. Combining that with an anti-inflammatory that also increases the risk of gastric ulceration is a recipe for [complication].”

The differences between patients suitable for bariatric endoscopies and those suitable for bariatric surgeries were marked, Dr Sartoretto said.

“These are fundamentally different patients,” he told InSight+.

“The average body mass index (BMI) of a patient undergoing the [laparoscopic] sleeve gastrectomy, for example, is about 46. With an endoscopic sleeve or even a gastric balloon, the average BMI is about 36. We’re not entirely treating the same population.”

Research in the field is looking at combining bariatric endoscopy with metabolic options, Dr Sartoretto said.

“We’ve seen a device that was developed about 8 years ago now but has recently received what’s called breakthrough status with the Food and Drug Administration in the US,” he said.

“This is a device looks at resurfacing the duodenal mucosa to improve glycaemic control. A study has demonstrated that this device was able to improve HbA1C by an average of about 1.2 percentage points, and that improvement was sustained over a period of 2 years.

“The future is going to be in the combined application of these varying technologies or medications.

“Certain fields in medicine have been using multimodal therapy for a long time. We see it in cancer medicine, we see it in cardiology. Bariatric medicine still remains at the point where either you’re having a surgery or you’re having a medication or something else.

“While each of these [emerging] individual therapies may not stack up to surgery at present, certainly combining them holds a lot of promise.”

Also online first at the MJA

Podcast: Dr Adrian Sartoretto, gastroenterologist and endoscopist with The BMI Clinic … FREE ACCESS permanently.

Perspective: Investigating the health impacts of the Ranger uranium mine on Aboriginal people

Schultz; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51198 … FREE ACCESS permanently.

Ethics and Law: Terra pericolosa: medical student involvement in intimate patient examinations or procedures

McGurgan and Calvert; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51181 … FREE ACCESS for 1 week.

more_vert

more_vert