WHILE acknowledging the federal government’s more generous than usual mental health funding, it is reasonable to say that around two-thirds of the $2.2 billion commitment made in the most recent federal Budget was directed towards business as usual.

By this we mean continuation of current Medicare funding and direct support for a select group of national organisations already holding government contracts. Even the very considerable and welcome boost for national community services for those who have attempted suicide is basically an expansion of existing efforts.

Despite rhetoric about structural reform, the government’s main effort boils down to the establishment of a suite of new community mental health treatment hubs ($541 million). Specifically, the budget delivers funding over the next 4 years for:

- eight new adult multidisciplinary mental health treatment centres;

- 24 new satellite centres;

- ongoing funding for the eight Head to Health Multidisciplinary Mental Health Treatment Centres originally funded ($114.5 million over 5 years) as part of the 2019–20 Budget as a trial, with one centre to be established in each state and territory. It is not clear that any of these original centres is yet operating, but in a recent interview on ABC Radio, Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister for Mental Health and Suicide Prevention David Coleman suggested they would all be operational by the end of 2021; and

- 15 new Head to Health Kids Centres (aged 0–12 years).

Many inquiries, such as that recently conducted by the Productivity Commission (2020), have pointed to the absence of community mental health care as a key deficit in Australia’s broken mental health system. So, this new emphasis is most welcome.

However, and only days after the federal Budget, the Victorian Government then released its state budget, which included a whopping $3.8 billion allocation to mental health, in response to that state’s own Royal Commission recommendations. One large chunk of this spending was the first tranche of funding for new community mental health services, as follows:

- 50–60 new Adult and Older Adult Local Mental Health and Wellbeing Services;

- 22 Adult and Older Adult Area Mental Health and Wellbeing Services; and

- 13 Infant, Child and Youth Area Mental Health and Wellbeing Services.

Who are the new services for?

Leaving aside key issues regarding planning and coordination between the different levels of government, and not forgetting Australia has nine jurisdictions not two, these competing budget announcements raise a fundamental question: who are these new services for?

The consensus appears to be a group of people called “the missing middle”, with both the Productivity and Royal Commission reports using this term to describe a group of clients too complex for primary care and basic psychology services, but not unwell enough to qualify for acute admission or ongoing management by state-run mental health services.

As there are so many gaps in our system, it may seem unreasonable to critique one aspect; however, the missing middle thus described seems particularly loose.

To what extent would a better (any) response to the missing middle result in reduced pressure on acute services? Do people with acute schizophrenia, recurrent bipolar disorder, or severe depression discharged from acute care become part of the missing middle in that they still clearly need community mental health care to prevent or relapse or readmission? To what extent do people in this missing middle recover, or is the goal simply better management of chronicity?

While policymakers, funders and academics contemplate this complexity, it is possible in Australia to find very rare examples of services already operating effectively in this chasm. They typically perform financial and organisational gymnastics at an Olympic level, cobbling together disparate streams of funding and service to meet client needs, despite the systems they operate within.

An island in the missing middle

One example highlighted by the Royal Commission is First Step, a for-purpose mental health, addiction, and legal services hub operating for 20 years in the heart of St Kilda, Victoria, and seeing about 2500 people a year. About 20% of First Step’s funding is derived from four separate streams of Medicare funding (Medicare Benefits Schedule, Practice Incentive Payments, Workforce Incentive Payments and Better Access). Another 35% comes from four separate streams of Primary Health Network Funding, each with distinct relationships and lines of accountability. Around 30% comes from five streams of funding from the Victorian Government across two departments. And finally, some 15% of funding comes from 15 separate philanthropic trusts, essential to keeping the doors open.

The funding model underpinning this service typifies the complex and byzantine arrangements that many mental health organisations must establish to survive. The energy and transactional costs are colossal. The resulting instability inhibits longer term planning and workforce development.

First Step has its origins in supporting people with co-occurring mental ill-health and addictions, precisely the type of complex yet common comorbidity that is well beyond the very limited scope of single practitioner, fee-for-service Medicare-backed interventions provided by most GPs, psychologists and private psychiatrists. These people typically live in our communities with levels of distress and impairment below the threshold required for acute admission to state-funded services.

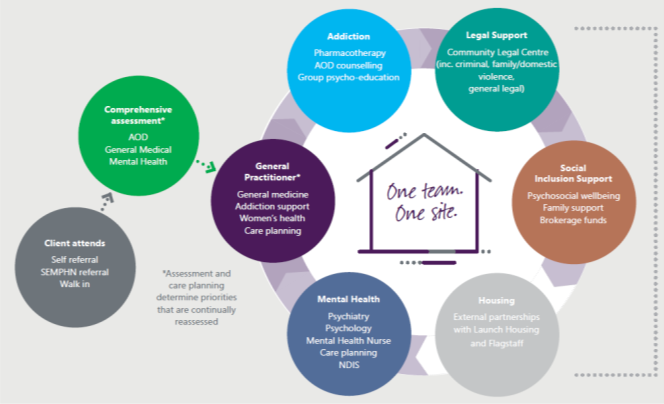

Importantly, the clientele includes people who grew up in out-of-home care, people who are homeless (including rough sleeping), people at risk of violence and self-harm, and survivors of childhood neglect and abuse, among other complex characteristics. First Step recognises six key domains for action and directly addresses five of these, with housing support provided through referral and collaboration (see Figure 1 below, noting the professions/support areas under each).

Figure 1

Let’s consider some of the key componentry for this kind of complex service to be established and successful.

Many people with complex mental health problems face financial difficulties. First Step provides care at no cost to the client. The multidisciplinary workforce realises First Step’s funding mix may never make them wealthy. However, they are stimulated by the collaborative and collegial environment and the opportunity to see the positive impact they have on clients’ lives. Highly skilled clinical and non-clinical staff meet face to face on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis to plan and implement coordinated and person-centred care for as long as it is required.

But having a GP, psychologists, psychiatrists, a lawyer, a psychosocial support worker, and others work as a team is not simply a matter of putting them in the same building. Frameworks are required for role clarity and to maximise impact. Team size (not too big) and close proximity are key. Staff need to know each other and to be able to walk across the corridor to engage their colleagues.

Long term engagement permits the establishment of trust between client and treating team, as well as the development of long term relationships with a community of support. Chronicity may vary over time but the organisation endeavours to remain a trusted source of support – a (health care) home. Appointments are made and kept, and when a new staff member is added to a client’s team, they see that person at the same trusted location, usually on the same day as other consultations. This increases motivation among clients and reduces drop-outs or so-called did not attends. First Step has no geographical or other eligibility criteria for most of its services.

First Step was recently awarded its first ever funding from the Victorian Department of Health for a 12-month Integrated Care Pilot.

Key lessons for current planning

The key lesson from First Step is that for many of their clients, the key to recovery will be a long term and sustained engagement across the six key domains. The federal government consultation paper on their new adult mental health hubs indicates the services they will offer will be short term or medium term. Excluding the most vulnerable in this way appears a wasted opportunity when gathering a multidisciplinary team at considerable expense.

With the term “missing middle” so loosely defined, federal and state planning for new community mental health centres can proceed with the potential for intergovernmental duplication, waste and, most importantly, ineffective care. If this supposedly subacute group is not in governments’ definitions of missing middle, then, who will be adequately resourced to care for them, because current systems are manifestly inadequate? What can we learn from the First Step example to answer that question?

A genuine response to the complex terrain of the missing middle merits clearer definition of expected clients and their ongoing needs with a recognition that for many, the aim is to facilitate incremental, whole of life improvements. Building the services that can respond to this challenge requires workforce, funding, payment, and smart service design. These need to be supported and then scaled up, so they can be available in the communities where they are most needed.

Recent budgets have confirmed governments’ understanding of the need for a systemic overhaul in mental health. But in our excitement to launch innovative solutions we must look to the examples, however rare, that have already been tested by the years and are saving lives. At every stage of reform we must adhere to first principles, and develop solutions that are based on true understandings of the problems they are trying to fix.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg is a Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney.

Patrick Lawrence is the CEO of First Step.

Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director of the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

I agree. A am a GP.

Federal government setting up new corporate style organisations that have the power to put in “exclusion criteria”, and to close their lists, mean that GP’s are once more left with the hardest cases and no-where to refer.

The solutions lie in bolstering the State health services. They understand that the “watering down” of the community services (as clearly is the case with Headspace) results in pressure on ED’s and in-patient services. They have the incentive to manage the harder outpatient cases that are too difficult for GP’s and community psychologists, thus preventing the extra pressures.

I have not even read the above,

however I wish to express my dismay at the treatment of suicidal attempt patients at some hospitals and I have no idea if it is across the board,

One hospital assessed a suicide attempt person with a relatively new practitioner who sent the patient home, she, a relative of mine, completed the act sucessfully two days later.

the other a male in his 6’s living at home alone, attempted suicide by carbonmonoxide in his car, was sent to hospital, and kept in emergency department till 11.30 at night, not offered a meal, spoken to by the pschyes, and other doctors and at 11.30 pm released to go home. alone.

this it would seem is a major crack.

Two analogies come to mind:

Plugging up the holes in a rusty bucket seems ridiculous when a new bucket (ie: model) is needed.

Spending money on fancy new silos without checking that the quality of the wheat going in is adequate, and that the product coming out is what the customer wants/needs. And what about all the other animals on this farm…?

.

The farmer (ie: the commissioning bodies) needs to actually know something about farming, and needs to make the tough decisions. The farmer needs to decide what the overarching principles of the farm are, instead of throwing taxpayers money up in the air and hoping it lands in the right place…

.

Clear principles that might be helpful when tackling the ‘missing middle’ are those such as:

1. The biomedical approach towards psychological ill health is past its ‘use by’ date (its akin to ryegrass going into the silos when it should be wheat). Someone needs to get us back to a true bio-psycho-socio-cultural model.

2. Recovery works best when psychological fitness and mental health maintenance SKILLS teaching is the foundation.

3. ‘Resilience’ is best achieved when there is an interweaving of acceptance plus change strategies.

4. Capacity building is imperative.

5. Clinicians need ‘core competencies’ and someone should regularly assess whether people actually have, and actually use, these competencies.

6. Money spent on management and niche ‘brand named’ services should be kept to an absolute minimum.

7. Phone services are inherent in any overarching framework and should operate from a clear evidence guided model so that users know where to turn and know what they will get from that service.

Services using volunteer ‘hands-on’ workers (eg: Lifeline) and police/emergency services should be decentralised because they are not adequately trained in mental health problems.

8. Treatment plans work best when there is a proper team approach embedded.

9. The most logical place to teach psychological fitness and mental health maintenance skills is the classroom… Abolish the WTF (waiting to fail) approach.

10. Lived experience should be used AND not misused.

11. It would be helpful to clearly acknowledge that many people have been let down or harmed by previous approaches.

.

There is no clear articulation of the underlying principles when these problems are mentioned.

.

Please stop trying to plug up the bucket with fancy band-aids… We need a new overarching model not more money… And we need clear articulation of what the farm is trying to produce… The farmer needs to produce many crops and raise many livestocks, and it always will..

.

Apologies for the length of this comment – but where else can hands-on clinicians have a voice?

Any monetised without oversight becomes a monster! If money is poured into mental health and ‘corporate’ mentality sets in (with positions such as ceo), then this ‘business’ will never end. I am a practicing doctor and I think the psychiatristists should review the efficacy of their (currently failing) treatments. Most psych patients now consume intensive care resources. And why is that most psych patients are white? Is it because other coloured people not given treatment- and also don’t want to exploit the system by claiming benefits from diagnosis (including the privileges that come from it such as the right to violently attack health personnel)? Soul searching is needed.