THE new “TGA-assessed” symbol and AUST L(A) listing on complementary medicines are meant to alert consumers that the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) have assessed the product’s health claims and found them supported by scientific evidence.

On 26 May 2021, Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max became the first herbal complementary medicine to receive Aust L(A) listing. This decision calls into question the evidence assessment undertaken by the TGA.

Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max contains herbal extracts of Prunus africana (Pygeum), Serenoa repens (Saw palmetto extract), Epilobium parviflorum (willowherb), Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin seed oil) and lycopene (found in tomatoes and some other red fruits and vegetables).

The TGA-assessed indication is, “For the relief of nocturia (night-time urinary frequency) associated with medically diagnosed benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH)”.

We could find only one published article about this product, authored by Coulson et al, published in 2013. The study was funded by Caruso’s (Natural Health Pty Ltd) and performed by Australian contract researchers. It was called a phase 2 randomised double-blinded trial and recruited 60 otherwise healthy males aged 40–80 years who presented with medically diagnosed benign prostatic hypertrophy. Three participants dropped out after randomisation, leaving 32 taking the herbal capsule and 25 a matched placebo for 3 months of treatment. Blinding was not assessed by asking participants to guess their treatment allocation.

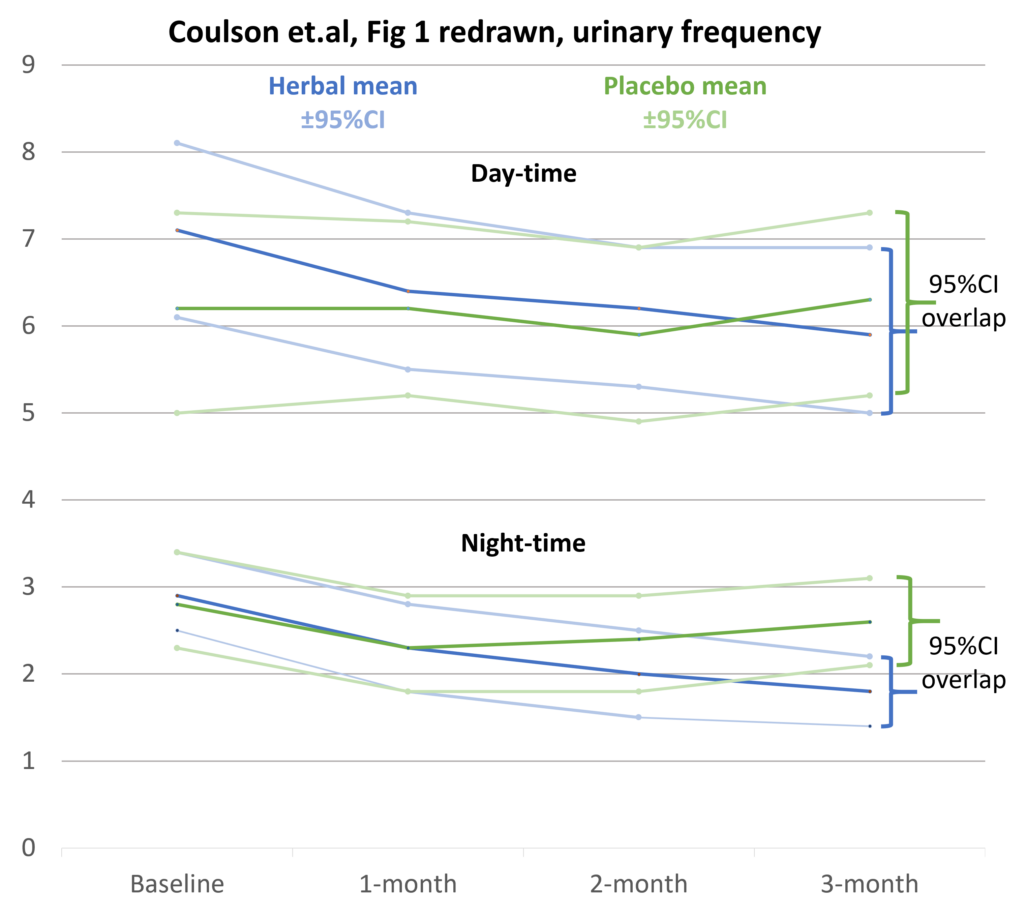

Figure 1 (A and B) in Coulson et al showed changes in daytime and night-time frequency of urination in the herbal and placebo group, measured by a daily record in a patient diary, with the frequency averaged at 1 month, 2 months and 3 months.

There are several discrepancies between the urinary frequencies reported in the text of the article and the tables in Figure 1. In addition, the graphs do not include zero in the y-axis; therefore, small trends and differences are exaggerated. Furthermore, they fail to show the ± 95% confidence intervals of the mean urinary frequency at each time point. These problems raise questions about the quality of the research and the conclusions reached. Based on our own calculations, we have re-graphed the data below showing the ± 95% confidence intervals.

The TGA Evidence guidelines for listed complimentary medicines (page 41) say:

“Confidence intervals of 95% are commonly employed to show the range within which the true outcome value could be expected to occur with 95% certainty. When 95% confidence intervals are generated for primary study outcome measures, the 95% confidence intervals of the intervention and exposed groups must not overlap”

The Figure 1 (B) table in Coulson et al and our redrawn graph show overlapping 95% confidence intervals of the herbal and placebo groups at 3 months. This casts doubt on the results of the statistical tests reported as showing the night-time urinary frequency significantly reduced in the herbal group compared with the placebo group (P < 0.004). The latter cannot be checked as we have no access to the raw data.

In addition, P values are problematic. Confidence intervals give the best estimate of the actual effect and indicate the extent of uncertainty in the results.

The primary outcome of the trial was the seven-question validated international prostate symptom score (IPSS). The question on nocturia asked: “How many times did you typically get up at night to urinate (0–5)?”

There was no significant difference in the scores of individual IPSS questions between the herbal and placebo groups over 3 months except for night-time urination frequency, which was said to show a statistically significant reduction from a mean score of 2.5 to 2.0 at 3 months (P < 0.05). However, as raw data were not provided, this result could not be checked. In addition, it is not in keeping with the finding of overlapping confidence limits for the night-time urination frequency means. Editorial comment on this study by Kaplan is scathing.

Coulson and colleagues did state:

“The major limitation of this preliminary clinical study is the relatively low sample size and the lack of comparative studies that have investigated the herbal combination. Hence, further clinical studies on a larger sample cohort with the addition of more objective outcomes such as flow rate are required”

We asked Caruso’s if they had conducted additional, more definitive, clinical studies on their product. We have not received a response. This raises a serious question – why did the TGA gave an AUST L(A) listing to this product?

The United States Food and Drug Administration has not approved any herbal medications for treatment of an enlarged prostate. Registered prescription products (α-blockers alone or in combination with 5-α-reductase inhibitors) are currently the medical treatment of choice for BPH.

Has Caruso’s provided more definitive (albeit unpublished) clinical trial results to the TGA? If so, the TGA should critically assess these studies and place a summary in the public domain, as they do with newly evaluated registered products (AusPARs). This would allow health professionals and consumers to make an objective comparison of the Caruso herbal product compared with current registered medical treatments such as the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin (Duodart). Without this, the TGA’s AUST L(A) assessment of Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max product does not engender confidence.

The AUST L(A) pathway was introduced on 19 March 2018. It allowed sponsors of complementary medicines to list their products using intermediate level health claims if supported by a pre-market assessment of scientific evidence by the TGA (“Purpose of the Bills”). The aim was to encourage more evidence-based products and help consumers choose them by designating them AUST L(A) and allowing a “TGA assessed” symbol on the pack and promotional material.

Three years later, there are only two AUST L(A) products listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). In addition to Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max the other is Care Pharmaceuticals Hydralyte Orange Flavoured Effervescent Electrolyte Tablets. The latter product is unremarkable – its indication is “decrease/reduce/relieve symptoms of dehydration”. There are 47 other AUST L(A) Hydralyte products on the ARTG with the same indication.

The paucity of AUST L(A) products after 3 years suggests that the industry considers a better return on investment comes from spending money on celebrity endorsement and promotional hype rather than undertaking research and paying the higher fees required for AUST L(A) listing or AUST R registration.

Complementary medicines labelled AUST L have no pre-market evaluation by the TGA. Sponsors self-certify regulatory compliance, including that they hold evidence for the claims made. TGA post-marketing surveillance assesses around 160 listed products a year (out of more than 10 000). Over the past 5 years, on average, about 75% of products evaluated have consistently been found non-compliant, mainly because companies were unable to produce evidence to substantiate claims for efficacy.

Given this, it is not surprising that the confidence of GPs and consumers in the TGA’s regulation of complementary medicines is low. The TGA’s assessment of Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max as AUST L(A) is likely to reduce this confidence even further.

Dr Ken Harvey AM is President of Friends of Science in Medicine, and Honorary Adjunct Associate Professor at Bond University.

Professor John Dwyer AO is Past President of Friends of Science in Medicine, and Emeritus Professor of Medicine at UNSW Sydney.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Thank you for your response Ken.

A revenue of $5.69 billion in 2021 by the Australian complementary medicine industry fully supports the urgent need by industry to fund rigorous clinical trials by Australian research institutes.

The Friends of Science in Medicine (FSIM) have an important role to ensure the research is done and to explicitly support Australian University and Institutes to research Complementary Medicine products.

We know already that a significant amount of funding to Australian Medical Research Institutes, not only comes from NHMRC funding, but also from external sources such as industry eg pharmaceutical industry and philanthropic donations.

It is to our best interest to support the Complementary Medicine industry to research their products but to remain cautious, at arm’s length to avoid any influence or biased results and any conflict of interest. This is where the FSIM can play a very important role. Thank you Ken for all your good work in highlighting these important issues in this space!

From Dr Ken Harvey (via the Editor)

In response to comments by Vicki Kotsirilos and Nigel Pollard,

A 2021 Australian complementary medicine industry snapshot showed a revenue of $5.69 billion, a growth of 15% per annum and export revenue of $1 billion. So, there is money to fund rigorous clinical trials if industry felt this worthwhile. Unfortunately, current policy settings provide a better return on investment from promotional hype and celebrity endorsement rather than research.

The TGA Assessed listed medicines evidence guidelines require a minimum of one double blind randomised controlled trial on the efficacy of the finished product and two examples of supporting evidence such as relevant scientific monographs &/or evidence-based reference texts for the ingredients used.

The published paper by Coulson et al does not support the TGA’s assessment of the Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max and supporting evidence on the two main ingredients is inconclusive.

Cochrane have reviewed Serenoa repens (saw palmetto) and concluded that, even at double and triple doses, it did not improve urinary flow measures or prostate size in men with lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with BPH.

As Vicki mentioned, Cochrane have also reviewed Pygeum africanum and concluded that, while it may be a useful treatment option for men with lower urinary symptoms consistent with BPH, the studies reviewed were small in size, of short duration, used varied doses and preparations and rarely reported outcomes using standardized validated measures of efficacy.

Nigel pointed out that the published trial did not adhere to CONSERT recommendations on reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal Interventions. Nor are they mentioned in the TGA Assessed listed medicines evidence guidelines. Extracts of the same herb are not equivalent unless they have been characterised as CONSERT suggests. This makes the TGA’s acceptance of evidence extrapolated from scientific monographs &/or evidence-based reference texts problematic.

The TGA has a legislated statutory Advisory Committee for Complementary Medicines (ACCM), which advises and makes recommendations regarding the entry of complementary medicines on the ARTG.

It would be of interest to know whether the ACCM supported (or indeed was consulted about) the entry of Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max as an Assessed Listed Medicine on the ARTG.

The AUST L(A) pathway was many years in the making. Its purpose was to assess the efficacy of specific complementary medicine products and therefore assist informed choice of products based on specific clinical evidence of efficacy.

Identifying products with specific clinical evidence is fundamental to evidence-based use of herbal medicine products. Typically they have multiple active components and are extremely complex to manufacture from the source genetic material of the herb, through growing, harvesting, processing, extracting and finished product manufacture. Therefore the finished product in its entirety is considered the active ingredient and batch to batch variability is assured by controlling all of these variables.

The importance of accurately defining herbal medicine interventions in randomised controlled trials was addressed by the expert CONSORT Group in 2006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16520478/ They provided a detailed checklist to ensure that investigators, editors, regulators and other readers of clinical trials are clear about the product that was used.

Unfortunately the description of Prostate EZE Max in the Coulson et al study mostly uses the unhelpful and incomplete “dry weight equivalent” description of the herbs used. This is far less valuable than, for example, defining the quality of a bottle of wine by how many grapes were pressed into it. The definition of the product used in Coulson et al is therefore not sufficient to make the study reproducible or link it to a marketed product.

Even if the TGA has satisfactory grounds to establish efficacy for the AUST L(A) approval of Prostate EZE Max, a bigger question is whether the product is well enough defined and controlled in its manufacture to deliver this efficacy in the batch available for purchase

Thank you Ken and John for your detailed assessment of this one particular herbal product based on the one study published here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23642948/

It is a pity the TGA will not provide details how they assessed this product. From my experience I have found the TGA to be quite thorough and perhaps had the advantage of viewing the raw data of the study, which as you say you did not have access to.

Unfortunately there aren’t enough studies on Complementary Medicine sponsor products. This is a real concern considering the large profits they make. It would be interesting to explore why this is the case

– lack of funding from independent sources eg NHMRC, for patency reasons etc etc? Sponsors should be researching their products for efficacy and safety.

Unfortunately most studies of Complementary Medicine products published are small and of short duration. I agree with you the sponsor products have a duty of care to do more studies – there are many universities now in Australia who are ready and happy to do the research but lack the funding to do the research on a particular product. There is also a conflict of interest too if the sponsor was to fund the study.

The product Caruso’s Prostate EZE Max contains the following ingredients: herbal extracts of Prunus africana (Pygeum), Serenoa repens (Saw palmetto extract), Epilobium parviflorum (willowherb), Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin seed oil) and lycopene (found in tomatoes and some other red fruits and vegetables).

Did the TGA look at the evidence of each individual ingredient to help their overall assessment?

For example this old Cochrane review of Pygeum [probably needs updating]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11869585/ demonstrated

“A standardized preparation of Pygeum africanum may be a useful treatment option for men with lower urinary symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, the reviewed studies were small in size, were of short duration, used varied doses and preparations and rarely reported outcomes using standardized validated measures of efficacy.”

This seems to be a recurring issue with research into herbs – the trials are often of small size, short duration, variable quality and there is a large heterogeneity of ingredients (dosage, form etc) in each product which influences the overall conclusion.

Thank you for your detailed assessment of this mixed herbal product for BPH.

It would be good if you can also explore similar issues with pharmaceutical products also.

The cynic in me suggests that the TGA and/or the “government” have been influenced by the complementary medicine industry, and that for that industry, dollars is more important than health care…??

This begs the question: which politician has shares in the company? I am disgusted that the TGA has lowered their standards to this degree

Well done Ken and John for such a clear summary of this.

Transparency of decision making is so important for public and professional trust in our regulatory agencies including the TGA.

The US FDA seem to be much more comfortable in having open access for their processes, while in Australia commercial in confidence seems to be so often stated as a reason for lack of clarity regarding decisions made.

Does the TGA have more data on this product, or has the decision been made simply on the data shown by Ken and John to be less than convincing?

Some of the prescription drugs approved for treating the symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy are not very effective. Who knew that a herbal mixture could be effective and have no adverse effects?

We should be grateful to Ken Harvey and John Dwyer for critically appraising the published phase II trial of the herbal product. The 95% confidence intervals were tabulated in the original publication, but including them in the redrawn figure highlights the overlapping effects of the intervention and placebo.

The numbers used to show a significant decrease in night-time urinary frequency were mean values. However, the original publication also included (in Table 1) the median values for the individual symptom severity items which make up the IPSS total score.

While the mean values for night-time urinary frequency in the intervention group showed a decline each month, the median value for the number of times the men had to get up at night did not decline from month 1 to month 3. In that table, the significant difference at three months appears to be because the median in the intervention group remained at 2 while it increased to 2.5 in the placebo group.

Even if we accept that the results of the phase II trial showed some benefit in a small number of men for a short time, surely the conclusion should have been that there would need to be a phase III trial to confirm the outcomes and to see if they were sustained?