BETWEEN vaccine supply issues, confusion about the role of GPs, and changed advice for AstraZeneca, the Australian COVID-19 vaccine rollout is well behind schedule.

How can we make it easier for the majority of Australians who want to be vaccinated? Especially given all Australians over 50 years of age are eligible to be vaccinated from today (3 May).

There are tangible things we can do now to help people understand the benefits and possible risks of COVID-19 vaccination, and get the vaccine quickly as soon as they’re eligible.

Improve understanding

We know communication about COVID-19 hasn’t met the needs of people with low health literacy or those who speak different languages. These groups are also more susceptible to misinformation so it’s vital we communicate well to them.

Here are some practical things we can do:

- use standard terms: governments need to develop a national glossary for COVID-19 vaccination terms. This would standardise and simplify information for diverse communities. For example, the Department of Health provides a glossary for mental health terms, which can ensure patient information and translations for words like “care plan” are consistent

- write for year 8 reading level: one study of COVID-19 information found government information in Australia, the US and UK was too complex for many people to understand; and it was worst for Australia. Online “readability” calculators can be used to check health information is at the recommended year 8 reading level. Real-time editing tools help writers avoid acronyms and uncommon words, and use shorter, simpler sentences

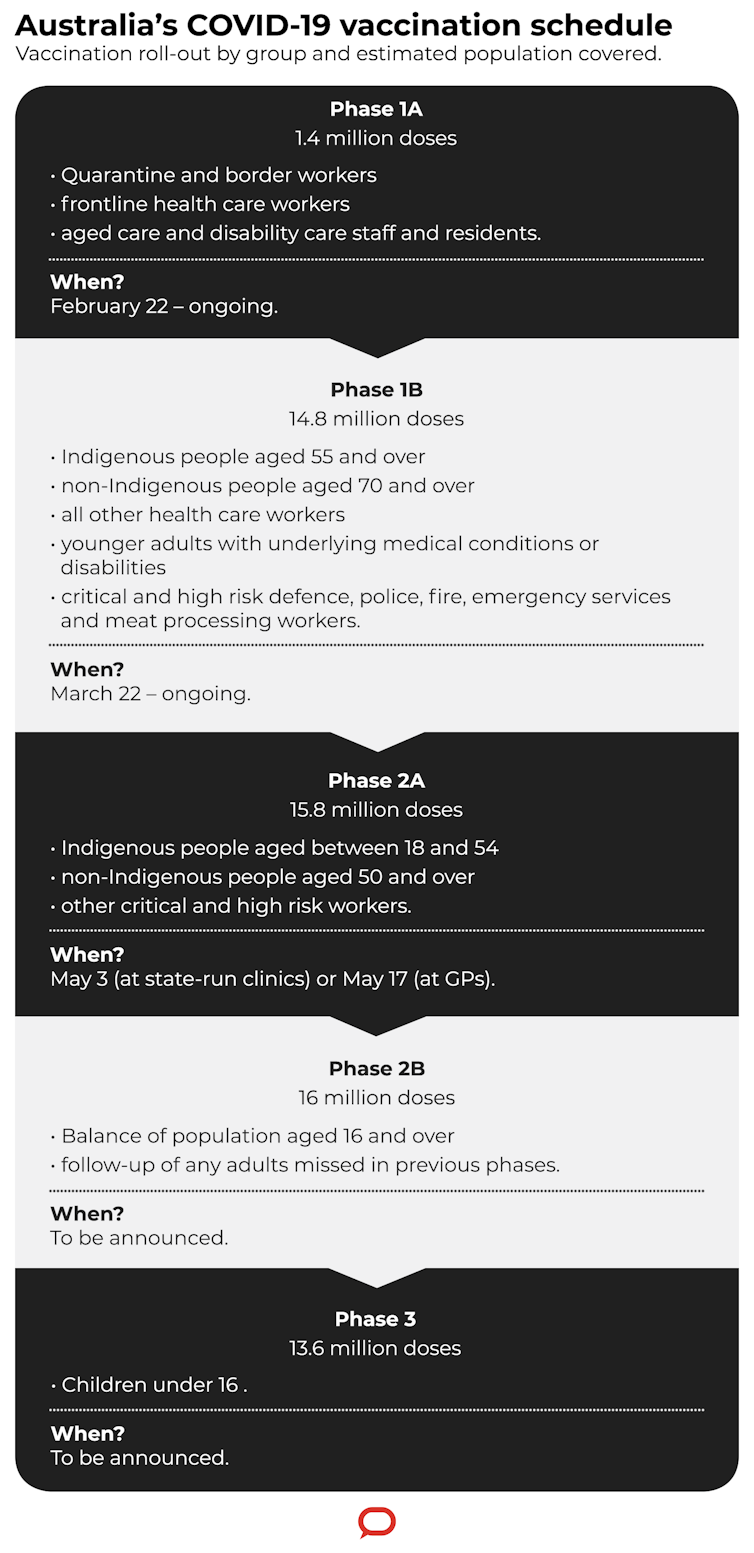

- use supporting images: we can make sure text is supported by helpful images such as the vaccination timeline, rather than negative images like pictures of needles that may scare people.

Improve access

We know vaccine supply is a challenge but we can still make sure every available vaccine dose is used as soon as possible.

Strategies to do this could include:

- local vaccination: our COVID-19 testing model has been successful including pop up clinics in places where there have been localised outbreaks. But our vaccine distribution logistics are falling behind. The US has used community clinics, pharmacies and mobile field officers to vaccinate millions of people a day. While some testing clinics now offer vaccinations, we could be doing more to provide vaccines for free as locally as possible

- national registry: registries can keep track of vaccine doses and notify people as soon as they’re eligible. This is done in childhood vaccination, and notification systems are used effectively for cancer screening programs. We could use the existing Australian Immunisation Register to track and promote COVID-19 vaccination

- automated appointments: people could sign up for “opt out” appointments with their local GP or vaccination clinic. This means they would be automatically booked into an appointment as soon as they’re eligible and supply is available, or moved to an earlier appointment if there’s a cancellation. This pre-registration approach will reduce wasted vaccine doses when several doses must be used from the same vial in the same day.

Improve motivation

Our research, published as a pre-print in February 2021, shows motivation is a particular challenge for Australia. Many people perceive their individual risk of contracting COVID-19 to be lower given case numbers are so low, and many people therefore haven’t been as strict with distancing behaviours.

Even before the new risk of serious clots was identified with the AstraZeneca vaccine, the top barriers for getting the vaccine in 2020 were safety concerns and side effects, which may outweigh the individual risk of COVID-19 for some people.

But most Australians have high intentions to get vaccinated, and there are things we can do to maintain motivation:

- explain benefits AND risks: rather than focusing on single cases of serious side effects, we need to balance information in the media. We can use simple graphics to help people consider how the rare risk of serious side effects weighs up against the serious complications of COVID-19 for their age group during a local outbreak — which could still happen any time;

- emphasise community benefits: since COVID-19 is well controlled in Australia, we can focus on emphasising the benefits to the community of getting vaccinated. This might help people understand why they should get vaccinated even though their individual risk might be low. Our research in 2020 found the top motivators were “to protect myself and others” and “belief in vaccination and science”. Even if a 25-year-old views their individual risk of COVID-19 complications as low, protecting family, friends, and wider society may be important to them;

- provide incentives: getting vaccinated as soon as someone’s eligible could be linked to financial incentives. This has been used for childhood vaccination where access to childcare rebates is easier with up-to-date vaccination, and health professionals are incentivised to address vaccination gaps. However, this needs to be done carefully to avoid the concerns of coercive policies.

More coercive options include: mandatory vaccination, such as for certain jobs; financial sanctions like fines; and movement restrictions, including requiring a “vaccine passport” for travel.

These may increase vaccination uptake, but there are ethical concerns because such approaches could undermine trust and increase inequalities.

Australian vaccination communication experts have argued against a mandatory approach, in response to a suggestion Prime Minister Scott Morrison made in August last year that a COVID-19 vaccine would be “as mandatory as you can possibly make it”, which he later retracted.

We could be doing much more to improve understanding, access and motivation among Australians right now. We need to ensure everyone has the information they need to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as they’re eligible.![]()

Dr Carissa Bonner is a Research Fellow in the School of Public Health at the University of Sydney.

Dr Rachael Dodd is a Research Fellow in the School of Public Health at the University of Sydney.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

more_vert

more_vert

Good commentary. Let me raise three discussion points.

First, incentives work better than sanctions. Once a person has been vaccinated, why can’t they be permitted to self-isolate at home (as opposed to a quarantine hotel) if exposed to the virus in a designated “hot spot”? Their risk of transmission would have to be very low.

Second, why are private hospitals not permitted to vaccinate their own clinical staff? Most run an effective in-house influenza vaccination program each autumn. Private hospitals have been utilized as vaccination hubs for both staff and surrounding communities in other countries, such as the UK and India. We have a strong private hospital sector in Australia and should use it to augment COVID vaccinations in public hospitals and general practices.

Third, adults under 50 years of age in categories 1a, 1b and 2a should be given the option of receiving the Astra Zeneca vaccine now, subject to informed consent and perhaps exclusion of active autoimmune diseases which may predispose to platelet factor 4 antibodies (thought to be the cause of the thrombosis/thrombocytopenia syndrome). At present they have no option (at least in some states) except to wait for the availability of the Pfizer vaccine, optimistically expected in Oct-Dec. Winter is coming!