WE conducted research to examine how Australians change their enrolment in private health insurance (PHI) during the pandemic. Specifically, we examined who has dropped, downgraded or upgraded their PHI since March 2020.

Most private health insurers increased their premiums in October 2020 and have scheduled another price rise for April 2021. At the same time, during the pandemic, one in four Australians have reported that they have been financially stressed in 2020. This number is even higher among the young: for example, 35% of those aged 18–44 years reported they are financially stressed. Because private health costs account for an increasingly larger percentage of monthly expenses, many may wonder if they should downgrade or drop their PHI altogether.

This analysis uses data from Taking the Pulse of the Nation Tracker – Melbourne Institute’s survey of the impact of COVID-19. The aim of the weekly survey is to track changes in the economic and social wellbeing of Australians living through the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic while adapting to various changes in federal and state government policies. The survey contains responses from 1200 persons, aged 18 years and over. The sample is stratified by gender, age and location to be representative of the Australian population. The current analysis draws on survey responses collected in 19–23 October 2020.

During 19–23 October 2020, the Taking the Pulse of the Nation Tracker survey asked respondents whether they currently have PHI; if not, whether they have dropped their PHI since March 2020; if so, whether they downgraded or upgraded their existing PHI since March 2020.

About 15% of PHI members downgraded or dropped their insurance during the pandemic

Overall, 60% of our respondents reported they currently have PHI. Since March 2020, 4% of those with PHI have dropped their cover entirely and another 11% have downgraded their existing PHI cover. On the other hand, 6% of the members have upgraded their PHI to a more expensive plan, likely due to anticipated use of private care.

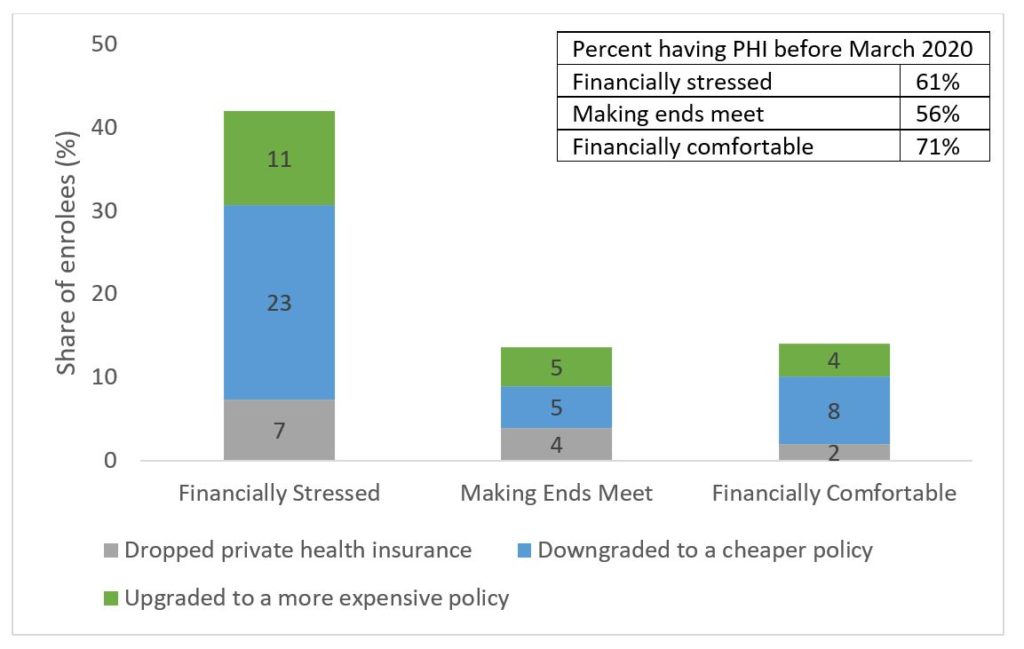

People in financial stress are three times more likely to drop or downgrade their PHI than those making ends meet

People in financial stress were more likely to drop their PHI (7%) than those making ends meet (4%) and those financially comfortable (2%) since March 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of people who dropped, downgraded and upgraded private health insurance (PHI) since March 2020, by level of financial stress (%)

Source: Taking the Pulse of the Nation wave 21 survey data, with 1200 respondents in each wave. The sample is stratified by gender, age and location to be representative of the Australian population. The vertical axis indicates the proportions (%) based on weighted responses.

A similar pattern was observed for the proportion of people downgrading: 23%, 5% and 8% respectively. Overall, people with financial stress are three times more likely to drop or downgrade their plans than those making ends meet or who are financially comfortable. On the other hand, they are also twice as likely as non-financially stressed people to upgrade their PHI; this is primarily driven by those living with children aged under 18 years.

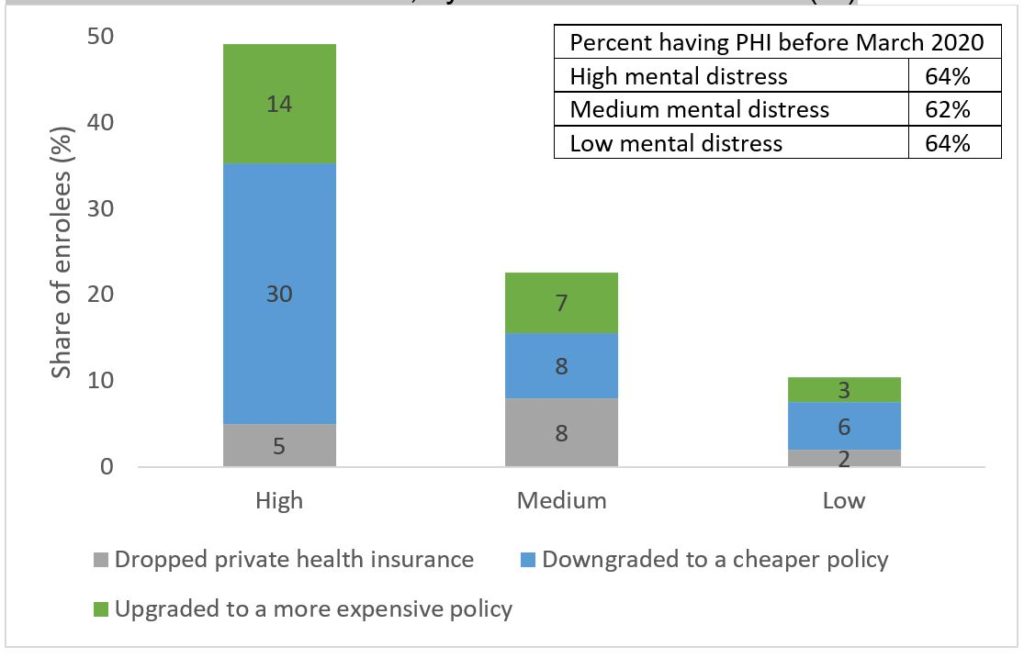

Those with high mental distress are five times more likely to change their PHI than those without mental distress

People with high mental distress are nearly five times more likely to change their PHI than those with low mental distress (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percent of people who dropped, downgraded and upgraded private health insurance (PHI) since March 2020, by level of mental distress (%)

Source: Taking the Pulse of the Nation wave 21 survey data, with 1200 respondents in each wave. The sample is stratified by gender, age and location to be representative of the Australian population. The vertical axis indicates the proportions (%) based on weighted responses. We categorised mental distress to high, medium and low levels by using answers to the question “during the past week, how often did you feel depressed or anxious?” in the survey. We define those responded with “most” to “all” of the time as high mental distress, those responded with “some” of the time as medium mental distress, and those responded with “a little” or “none” of the time as low mental distress.

For example, 30% of those with PHI and with high mental distress downgraded their PHI, while only around 6% and 8% of those with low or medium mental distress did so. Additionally, 14% of PHI members with high mental distress upgraded their coverage, while only 3% of those with low mental distress did. Many of those upgraded polices may cover more psychiatric services.

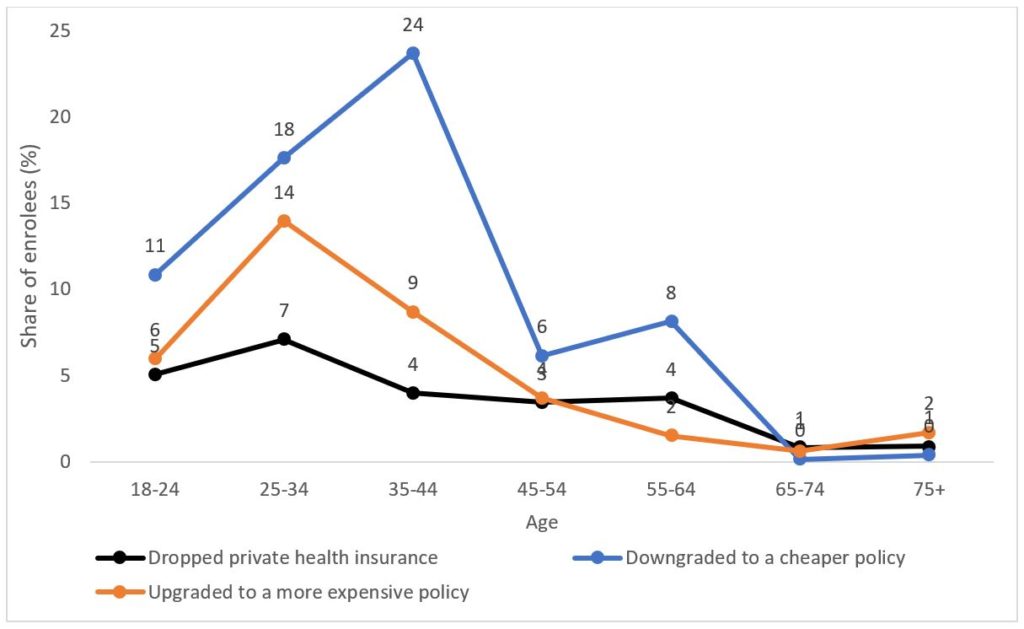

PHI members aged 18–44 years are more likely to change (drop, downgrade or upgrade) their PHI during the pandemic

PHI members aged 18–44 years old are much more likely to change their PHI during the pandemic than older members (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percentage of people who dropped, downgraded or upgraded private health insurance since March 2020, by age cohort (%)

Source: Taking the Pulse of the Nation wave 21 survey data, with 1200 respondents in each wave. The sample is stratified by gender, age and location to be representative of the Australian population. The vertical axis indicates the proportions (%) based on weighted responses.

For example, 24% and 18% of those aged 35–44 years and 25–34 years respectively downgraded their insurance cover, compared with only 6% of those aged 45–54 years, and 8% of those aged 55–64 years; less than 1% of those aged 65 years or more did so. Similar patterns were observed for those who dropped PHI. Interestingly, 14% of those aged 25–34 years and 9% of those aged 35–44 years upgraded their PHI during the pandemic, likely due to their anticipated use of services such as childbirth in private hospitals. Very few people older than 65 years have changed their PHI since March.

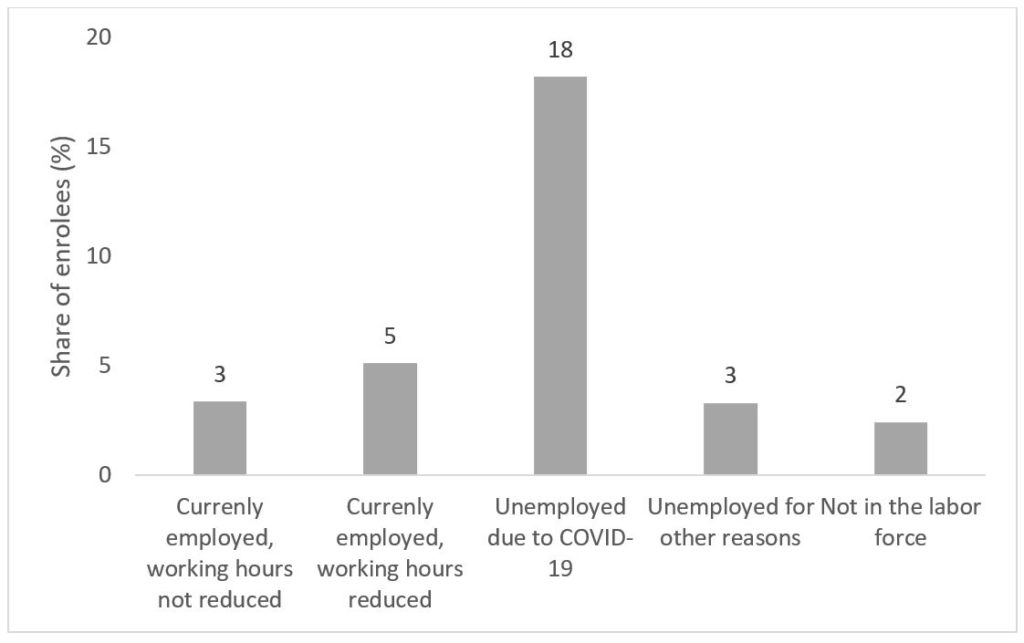

Over one in six PHI members who became unemployed due to COVID-19 dropped their PHI

Among those holding PHI who have become unemployed due to COVID-19, 18% of them have dropped their PHI since March (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentage of people who dropped private health insurance since March 2020, by employment status

Source: Taking the Pulse of the Nation wave 21 survey data, with 1200 respondents in each wave. The sample is stratified by gender, age and location to be representative of the Australian population. The vertical axis indicates the proportions (%) based on weighted responses.

In comparison, only 3.3% of those who are unemployed for other reasons dropped PHI during the pandemic. This is striking since both groups report similar rates of PHI (47% for the former and 45% for the latter).

The rates of dropping PHI are much lower among those who are currently employed with same working hours (3%), currently employed with reduced hours (5%), or not in the labor force (eg, retired, 2%).

Conclusion

Re-evaluating PHI options as your situation changes

The potential value of purchasing PHI consists of two components: protection from potentially very high health costs (protection against financial risks), and expected use of private hospital care.

First, value from risk protection is arguably small, given Medicare covers Australians’ health needs in public hospitals. People are therefore protected from the financial risk of catastrophic health problems. Second, there is value in buying PHI if people expect to use private hospital care; this could be for reasons such as reduced waiting times for certain elective surgeries or having a choice of doctors.

As the expected use of private hospital care and financial situation changes, re-evaluating one’s needs for PHI in situations such as a pandemic is generally recommended. Our data suggest that people are doing so in response to COVID-19.

Many non-urgent elective surgeries and some routine health care procedures (eg, dental care) were delayed or suspended due to COVID-19. In response, people may downgrade or drop their PHI. In the period from March to October 2020, among those who had PHI, 11% downgraded their existing PHI, and 4% dropped their PHI.

Since March, only 6% of Australians upgraded their PHI, but they were concentrated among childbearing young adults, with 14% of those aged 25–34 and 9% of 35–44 upgrading their PHI. For both of these age groups, most do not need private care for chronic elective surgeries such as hip or knee replacement. More likely, they upgraded their PHI because they are planning to have children.

Making PHI more valuable to the young

The Australian private hospital insurance sector is in trouble, with young people abandoning memberships; remaining members tend to be older and more likely to use health care. As a result, insurance premiums have been driven up further, which likely leads to even more young people dropping out. The June 2020 issue of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)’s PHI statistics report showed that 44% of all Australians held PHI, but uptake rates vary substantially by age, ranging from 22% among those aged 25–29 years to 56% among those aged 70–74 years.

Our data also show that young people aged 25–44 years were most likely to change their PHI during the pandemic, with 28% of those aged 35–44 years and 25% of the 25–34 years age group dropping or downgrading their PHI, with downgrades more likely than upgrades.

People drop PHI when they do not feel they are getting value from purchasing it. On average, the potential value from PHI is much lower than premium costs young people have to pay. In response to this, starting from April 2019, the government allowed insurers to provide young people aged 18–29 years discounts of up to 10% of their premiums. However, this policy has not been effective so far and is unlikely to solve the problem because premium discounts are very small compared with the large difference between expected benefits and premiums for those in the younger age group.

Three main policies were implemented in 1997–2000 in Australia to encourage people to sign up for PHI (here and here): rebates to partially refund premiums, the Medicare Levy Surcharge that charges additional tax for people who earn above a certain threshold and do not hold private hospital cover; and the Lifetime Health Cover loading for young people who do not hold private hospital insurance after they turn 31. These policies, implemented with high costs to taxpayers, were ineffective in reducing the burden on the public system and have been controversial. It may be possible to implement a new policy that makes PHI valuable for all Australians by allowing premiums to align more closely with expected benefits.

The government has been tinkering with the rules with the PHI sector since 2017, trying to maintain coverage. This has been made more difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic, with households under significant financial pressure and with the length of the current recession unclear. Current government subsidies to the sector will fall as memberships decrease, and the use of private health care continues to decline. Repurposing these subsidies to support higher value health care for the population should be a key objective for government going forward.

Professor Yuting Zhang is Professor of Health Economics in the Faculty of Business and Economics at the University of Melbourne, and an expert on economic evaluations of health policy and health care reforms.

Dr Judith Liu is a Research Fellow at the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on the evaluation of healthcare policy and social welfare programs.

Professor Anthony Scott is a professor at the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research at the University of Melbourne. He leads the Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life (MABEL) panel survey of 10 000 physicians, and is a Research Lead Investigator on the NHMRC Partnerships Centre on Health System Sustainability.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert