AUSTRALIA’S first possible case of locally transmitted Candida auris – an emergent, multidrug-resistant yeast – was identified in a Victorian hospital in 2018, prompting warnings of the importance of greater awareness and research investment into this pathogen.

In a case report published in the MJA, researchers reported the detection of C. auris in a 70-year-old man with multiple myeloma who had been admitted to the Victorian hospital after being hospitalised in the UK 10 months previously.

Candida auris was detected in one of the patient’s urine samples prompting the screening of 73 ward contacts. One contact – a 38-year-old man with lymphoma – was also identified as having been colonised with C. auris. This patient had been treated at a hospital in the United Arab Emirates before being directly transferred to the Victorian hospital 3 months prior.

The isolates were confirmed as C. auris by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. The authors wrote that the median pairwise single nucleotide polymorphism distance between the two isolates was 167, which suggested that the isolates were related, but it was not possible to confirm transmission.

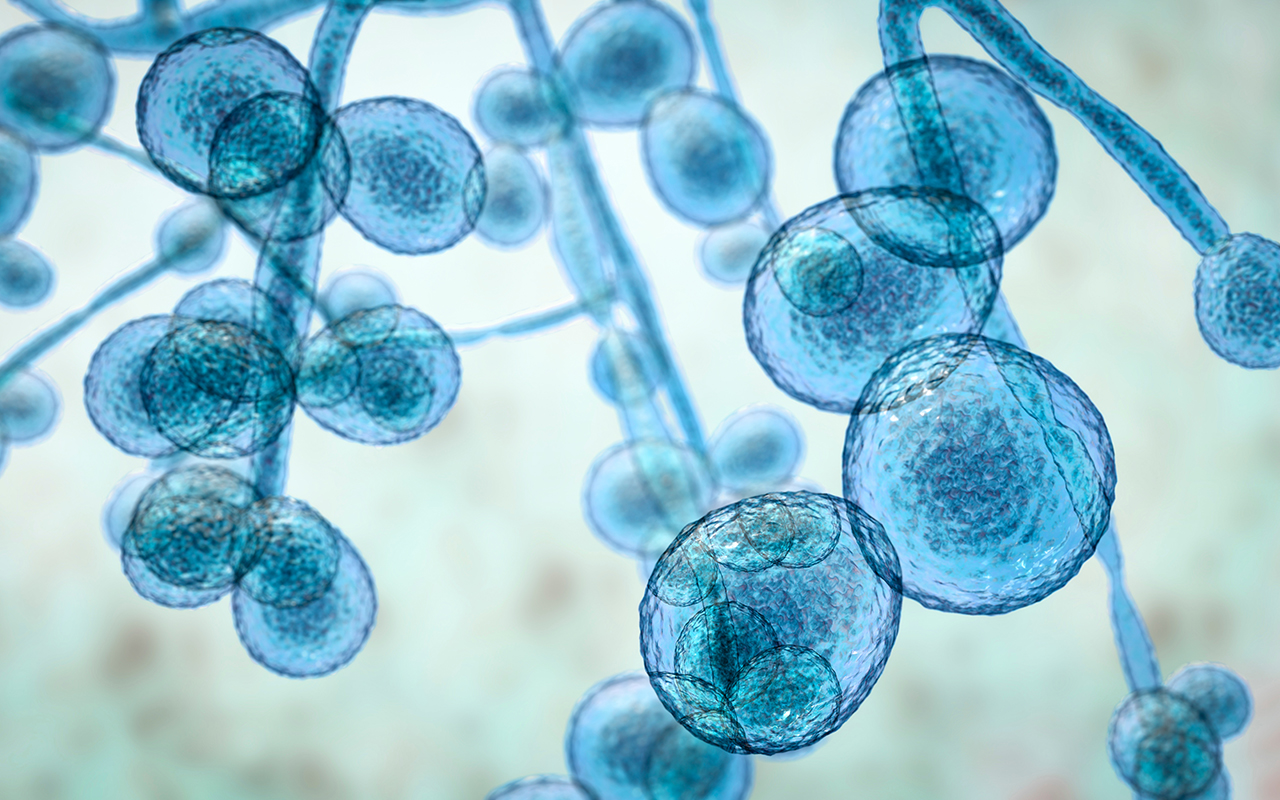

Candida auris was first recognised as a new species of Candida in 2009 and has been reported in over 30 countries, including the UK and the United Arab Emirates.

Associate Professor Leon Worth, lead author of the MJA paper and infectious diseases physician at Royal Melbourne Hospital’s Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre, said that it was fortunate that neither patient had developed a serious infection subsequent to colonisation with C. auris.

“It’s important to realise that neither [patient developed] infection. These patients did not require antifungal therapy and there is no role for treating an individual who is found to be colonised with C. auris whether it be in urine, in the gut or on the skin,” said Associate Professor Worth, who also spoke to InSight+ for an exclusive podcast.

“We believe these [cases] to be a harbinger to say: this is here, it’s present and identifiable.”

Associate Professor Worth said only a handful of cases had been reported in Australia so far – four in Victoria, three in New South Wales and two in Western Australia.

“But the message is that it’s not zero,” he said.

“Let’s not forget that prior to 2018 … [apart from one Kenyan visitor in 2015] we hadn’t had reports at all in Australia of C. auris, so this is something new. We have seen reports now of C. auris in about 30 countries across the globe, so Australia is probably one of the latter regions in which C. auris has emerged. There is now the potential for future outbreaks to be seen in Australia, given what we now has occurred in Europe and the US where there have been significant clusters of infections due to C. auris reported in health care.”

Professor Ana Traven, co-head of the Biomedicine Discovery Institute’s Infection and Immunity Program at Monash University, leads a mycology research lab studying fungal infections. She said the identification of these infections, and the possibility of local transmission, was concerning.

“This is fungal infection found in hospital settings or aged care facilities in patients who are otherwise very sick, people like cancer patients or people in intensive care,” she said.

This, she said, was one of several factors contributing to high mortality rate associated with C. auris, which the MJA authors noted was about 30%.

“We don’t know as much about fungi as we know about bacteria. For example, we don’t have as many treatment options, and treatment may start quite late if fungal infection is not suspected or is hard to diagnose,” Professor Traven said. “And then if you have a bug like C. auris, that is resistant to to a frontline drug – and there are also some isolates that are resistant to two or even all three of the drug classes we have – then you really have few options and treatment becomes difficult.”

Professor Traven said increasing awareness of C. auris was crucial, noting that in the UK, C. auris contamination had caused the closure of intensive care units in recent years.

“This particular fungus is quite unusual … in that it can contaminate the hospital environment very easily, things like bedding and so on, and it survives very well in the environment and is quite difficult to eradicate with standard infection control.”

Associate Professor Worth said the identification of a small number of cases in Australia had prompted the development of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of C. auris.

“This is a great example of … timely development of clinical guidelines and policy so that we can be prepared for an emergent threat. Clinicians that haven’t seen this as an issue year now have on hand relevant information and guidance,” Associate Professor Worth said. “This includes recommendations for contact tracing, and laboratory methods for detection and treatment of C. auris infections.”

Associate Professor Worth said clinicians treating C. auris would have to not use fluconazole, or other drugs in the azole class, which are often the first-line antifungal agent, due to resistance.

“Instead, the first line agent that is recommended is the echinocandin class of drugs, such as caspofungin, [which is] an intravenously administered antifungal agent,” he said. “Other agents, such as amphotericin or liposomal amphotericin may also be used, particularly if a patient was to have ongoing clinical instability or fever while receiving echinocandin as a first line therapy.”

Professor Traven said a key lesson to come from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was the importance of awareness, research, and preparedness for the emergence of new pathogens.

“We need to raise awareness of fungal infections in these settings,” she said. “Treating cancer, surgery, all of these interventions that we have come to expect with modern medicine, can be compromised if a patient becomes infected with C. auris. And once you get one of these infections, you don’t have a very good chance of surviving.

“We need to recognise that and invest into research and antifungal drug development to be prepared for the emergence of new pathogens such as C. auris, which is intrinsically resistant to some of the drugs that we have. We need to be prepared.”

more_vert

more_vert

I read Professor Worth’s post with interest and he correctly indicates that there were cases in New South Wales (three infections and one colonised individual) . Reassuringly for the present, the isolates of Candida auris were not multi-drug resistant., Whilst the scenario described by Professor Worth sought to link cases through local transmission, a report from NSW (Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2020) describes a situation where the genetic relationship of sporadic cases may differ from the case cluster context well described in the international literature. The interpretation of the median pairwise SNP difference between isolates (i.e. are they closely related or not?) should be made in he epidemiological context and will differ with the technical benchmarks used. One could argue that they may not be closely related. Given the call to vigilance by the post, it would be of interest and importance to know what measures Victorian institutions have instituted and what advice they have for other jurisdictions in early detection an infection prevention?