WITH two Royal Commissions, one Productivity Commission Inquiry and a Review of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) all underway concurrently, even by mental health’s standards it is a chaotic, pre-election environment. This article explores the context for one of these, the MBS Review, and considers how online psychological therapies could feature more prominently as part of a shift towards a fit-for-purpose, 21st century mental health system.

Mental health under Medicare now

The MBS Review Mental Health Reference Group has published its report and recommendations, part of the overall Professional Services Review into Medicare. It recommends very a significant expansion of the Better Access Program, which enables Medicare-subsidised visits to psychologists.

It makes this recommendation despite evidence indicating that the program is unfairly distributed across Australia in terms of geography and wealth, suffers from gender imbalance and high out-of-pocket costs (gap fees), and has had marginal, if any, impact on the prevalence of mental illness in Australia.

The program has been growing at about 7% each year, costing $1.45 billion in 2016–17. The average number of services provided per patient has been steadily declining, from 4.95 in 2011–12 to 4.64 in 2016–17, perhaps suggesting overall acuity — the measurement of the intensity of care required by a patient — in the client group has diminished. The number of new clients has also declined rapidly. These people should be the lifeblood of this program, designed as it was for short and targeted interventions for people with mild to moderate mental health problems. This is where the evidence for psychological therapies, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy, is strong, as a proportion of the total new clients into Better Access were 68% in 2008, 57% in 2009, and just 32.6% in 2016–17.

How the MBS Review wants to change Better Access

The Reference Group has proposed a significant expansion of psychology services under Better Access through making eligible:

- people without any mental health diagnosis;

- the family and carers of people with a mental illness who might benefit from psychological care; and

- people with moderate to severe mental health conditions requiring up to 40 sessions of psychology care in any year.

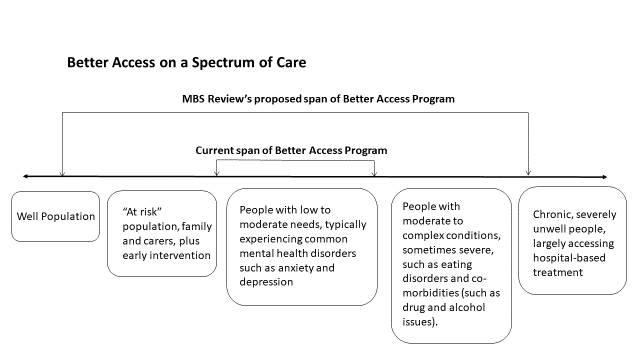

The recommendations therefore seek to increase the availability of Better Access at “both ends” of a spectrum of care, as shown in the figure below:

While purporting to shift from a “one size fits all” approach, the Reference Group seems to have chosen instead to simply make more of the one size available to considerably more people. Their service model focuses on an individual client attending the offices of an individual health professional. Medicare reimburses the health professional on a fee-for-service basis, with typically some additional out-of-pocket cost also payable by individuals to their treating professional. In 2016–17, the average out-of-pocket cost per session with a registered psychologist was $27, and with a clinical psychologist it was $32.

These additional out-of-pocket costs could have a significant impact on some of the more severe groups targeted by the MBS Review, given they may also be least likely to afford care. And more generally, the “right” number of sessions is very much a matter for debate. There is evidence indicating that therapy of brief duration but higher intensity (frequency) is more likely to be effective than therapy spread over a longer period.

Alternative approaches

The MBS Review group, mostly comprised of psychologists already operating under Medicare, surprisingly failed to emphasise alternatives to fee-for-service. In relation to people with more complex or severe problems, mental health care is optimally organised through a multidisciplinary team, comprising, for example, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a GP, a mental health nurse, a social worker, a peer worker, an employment support worker, a housing officer and others. This fact, and together with the inability of fee-for-service to generate this kind of teamwork, has already been acknowledged by the Department of Health.

At the other end of the spectrum of care, the MBS Review strangely ignores compelling evidence to support application of proven approaches to helping people with low intensity needs. Parts of Australia have already adopted a model focusing on the role of coaches, first developed in the United Kingdom.

Also ignored is the strong evidence indicating that online therapies can be effective either as an adjunct to, or instead of, face-to-face professional care. While they vary, these online approaches commonly present a course of psychological therapy, structured so the participant can track their progress over time and seek further assistance if their situation deteriorates. They can be critical for reaching traditionally underserviced groups, such as young people.

Example of online psychological therapy – e-couch

Some key advantages of the online approach include:

- the person can undertake therapy in privacy, at home;

- 24/7 availability;

- no fees;

- the person can dictate pace of sessions; and

- therapy does not depend on access to a health professional nearby — vital in rural areas.

Conclusion

Mental health represents 12% of the burden of disease but garners just 7.7% of health budget — this is 0.5% higher than in 1992–93 when the first National Mental Health Strategy was released. There is no doubt the area is much underfunded.

The National Mental Health Commission in its 2014 review suggested Australia’s mental health system, including the Better Access Program, was not fit-for-purpose. The MBS Review into mental health represents a colossal opportunity to get future investments right, to shift the focus from access to quality and what works. Online and team-based approaches are key to driving new models of quality mental health care. By contrast, the MBS Review recommends a massive 21st century investment in a 20th century model of fee-for-service care. We can do better.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg, is Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney and Fellow at the Centre for Mental Health Research, Australian National University.

Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless that is so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Care to declare your conflicts of interest here?

This piece is biased enough to begin with, has manipulations of data and terrible half truths and financial interests in advertised products hasn’t been declared.

Poor article.

Hear hear to what the consumers say. Generally speaking they have excellent bs detectors when it comes to mental health professionals.

Do either of these chaps have any financial or other interest in pushing online products?

Oh wait let me quote from his Uni of Sydney page “including new e-healthcare service systems, He is the Chief Scientific Advisor to, and an equity shareholder in, Innowell. Innowell has been formed by the University of Sydney and PwC to deliver the $30m Australian Government-funded ‘Project Synergy’. Project Synergy is a three year program for the transformation of mental health services through the use of innovative technologies…”

Since this wasn’t disclosed in the article, and the article wasn’t labelled an advertisement, I guess I won’t bother trusting anything published here.

Some other points to consider about the statement that the Better Access scheme “has had marginal, if any, impact on the prevalence of mental illness in Australia” and the recent study by Jorm (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0004867418804066):

* The majority of Australians with a diagnosed mental disorder (54%) do not access any form of treatment.

* Of those who do access care, the proportion is half that of people with physical disorders.

* ABS stats show that only around 7% of Australians access any mental health related services in Medicare. Only 3.2% of people see a psychologist.

* While mental illness is often a factor to suicide, we must not ignore other big contributing factors such as economic distress, chronic pain, and isolation.

* In Australia, men are three times more likely to take their own lives than women – and the highest rate of suicide is for middle aged men. Yet there is evidence that fewer than a third of male suicides are associated with depression.

Given the above, why would we expect distress to decline across the entire Australian population? Is it sensible to rely on the national suicide rate as a yardstick to measure the effectiveness of this scheme?

Population level data tell us next to nothing about the positive impact of the Medicare scheme, simply due to the fact that most people in the Australian population never access the program. If we want to know what impact any program has, then look at studies where we actually have data on those people who accessed that program, not population-level statistics.

I feel quite emotional and overwhelmed at the prospect of responding to this article, given the power differential between myself and the authors, who are high-profile mental health advocates.

As a vulnerable and disadvantaged mental health consumer that lives in a rural area, I feel distraught by Hickie and Rosenberg’s decade long campaign against Better Access.

I find their constant attacks on Better Access to be paternalistic, ideologically driven and lacking insight into the lived experience of mental health consumers.

Due to the lobbying by the likes of Hickie and his mates, people like me have had the rug pulled from underneath them. On the night of the 2011 federal budget when Hickie and McGorry were gloating about Headspace being funded and referring to Better Access sessions being slashed from 18 to 10, saying that people only needed 5 sessions, I was bawling my eyes out. This was a massive setback for me and others like me. Hickie’s continued lobbying against BA has caused considerable harm to mental health consumers. Does he ever factor that into his biased analysis and rhetoric.

Better Access has been a life saver for me and many of my peers. It is the number one issue that gets raised in the peer support networks I am involved with. The hypocrisy of Hickie’s stance is sickening, considering that he was a major driver for sessions being cut in the first place, given the fierce public campaign he ran and lobbying of federal politicians. It is shameful and disrespectful to mental health consumers.

Disadvantaged people like me, who have been caught up in the mental health system for years, want to be able to have the freedom of choice to access what services we need. We are the experts. We have experienced the styles of centre-based service provision that Hickie and Rosenberg propose. Those types of services have caused us considerable harm.

They remove choice and stop us from seeking help from a preferred practitioner. You have very limited options of service provider under centre-based models of care. That type of service provision has caused me great harm over the decades, due to not being in control of who you get to see, sometimes strict access criteria, inept and non-trauma informed staff, limited number of sessions or limited time you can access the service before being kicked out.

I support the MBS Review Mental Health Reference Group recommendations for more sessions, as do many other mental health consumers I interact with on a daily basis.

Ian and Sebastian, you do not speak for me.

As Emma states this is an over simplification. What is continually lacking in all the media both authors, and their associates are appearing in, are the Social Determinants that need to be addressed. If addressed the reliance on clinical services is reduced. Prior to the NDIS thousands of people with Psycho Social disabilities had funding for essiental assistance with daily tasks such as domestic duties, meal preparation, transport, respite, and so on. They also had access to public mental health services and case workers. These were removed by the states, as part of their agreements under COAG. The 64k deemed to be the number to meet NDIS criteria is grossly inaccurate, so the hundreds of thousands that do not become NDIS participants were, and are suddenly without previous supports. Actual interaction with real, and not carefully selected Lived Experience would have provided this aspect. As usual, another article biased and subjective article lacking supporting evidence.

The statement that the Better Access scheme “has had marginal, if any, impact on the prevalence of mental illness in Australia” needs clarification. The study supporting this claim, conducted by Jorm (2018), is based on trends observed in three separate sources of data – provision of MBS funded services by mental health professionals over a 9-year time period (Australian Government Department of Health Services), changes in psychological distress over a 14-year time period (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare), and suicide rate over a 14-year time period (Australian Bureau of Statistics). The study was not controlled, and for that reason, we cannot know whether factors like availability of mental health professionals or societal/environmental changes accounted for the trends. Furthermore, using the observation of trends approach to interpreting the psychological distress data, it appears that there is a decrease in high or very high psychological distress in the five years after the Better Access scheme was introduced, which is precisely where the scheme was targeted (e.g. “People with low to moderate needs, typically experiencing common mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression”).

It is clear that we need a rigorous and unbiased evaluation of the Better Access Scheme.

The whole reason that the amount of services per client has reduced is because the amount of subsidised sessions available has reduced. In 2013 it was 16 per calendar year, then reduced to 12, and now to 10.

Also, most face to face services are NOT practicing in the mild end of the spectrum, as we are all inundated with high end complex cases. Why? Because there are not enough mental health beds in hospital or crisis services. So clients use us instead of having nothing.

Please state facts, stop manipulating the data to suit your own personal vested interests in seeing e- health services funded more.

Clearly asking Psychologists to

Comment would be preferable as at least we are familiar with how the current system is already team based. Multidisciplinary MH private practices across the country already provide team based care, engage with other services such as General practice/psychiatry/paediatrics/housing/schools etc. and we do it on a fee for service basis, both through MBS, NDIS and PHN funding – the client chooses who they want to see, where and when, and they should have choice.

Ian Hickie seems to not understand how the system works on the ground, but that isn’t surprising as he is a researcher rather than a practice owner, and he isn’t a psychologist. If is about time psychologists had a voice, we are NOT about the money as Hickie alleges, the MBS rebate doesn’t even go to us – it belongs to the client/patient. As pointed out all clinicians require gap payment for sessions as the rebate for a psychologist less than half a GP rebate for the same item, and less than a third of a psychiatry rebate, AND thus most of the expense attributed to MH under the MBS is accrued my practitioners other than Psychologists.

The care model proposed in this opinion piece, for those with complex and severe mental illness, is NOT treatment – team care as proposed here, is aimed at improving quality of life for those with severe and chronic illness, helping them to “live with” their illness more effectively, in line with the poorly-named “Recovery” model. A noble and valid goal, but for the substantial group at this end of the Stepped Care continuum, whose illness is underpinned by complex trauma, this should NOT come at the expense of effective treatment. For many, the evidence of what works for this group remains overwhelming: long term psychotherapy with a single therapist, within the safety of a continuous therapeutic relationship. The fee-for-service model fits this treatment need well, without the excessive administrative costs associated with unnecessary team-based care. Complex trauma survivors deserve effective treatment of their illness – not just help to “live with it”.

The article above contains several disappointing inaccuracies. Readers should avoid taking this piece on face value, as the relevant facts have been presented in a misleading way. I remind both authors that we put people’s lives in jeopardy when we make it harder to access basic mental health care. And Medicare is one of the best mechanisms we have in Australia to distribute services across our population. We ought to look at ways of strengthening and improving that system, in addition to other wider improvements.

Readers should be aware that around this time each year, we see the same scare campaign running about the rising costs of Medicare-supported psychological care (http://drben.com.au/d/ten.pdf). Well before the Better Access program had even launched, the authors of the article above were expressing opposition to the system (http://www.abc.net.au/pm/content/2006/s1602036.htm). It is noteworthy that their opposition to Medicare is exclusively directed at psychological services. That is, we have yet to hear their objections to the fee-for-service model as it applies right across Medicare, from general practitioners, to psychiatrists, or mental health nurses. Put simply, the critique directed at psychological care in the Medicare system is one-sided, not a measured and balanced assessment.

The article above misinterprets postcode data to bolster the claims of the authors that the program serves the wealthy. IRSD statistics rank Australian postcodes across a wide range of factors – not just income – and many of those factors significantly reduce the likelihood of a person accessing psychological care (http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100052011). Living with a mental health condition is disadvantaging in and of itself. Therefore, to claim that those receiving psychological care are ‘undeserving’ flies in the face of the principle of the universality of Medicare. Why should mental health issues be discriminated against in the Medicare system?

The authors point to a steady decline in the average number of services per patient, without mentioning that the maximum number of sessions in the scheme was reduced across that period. In fact, it was on the advice of one of the authors of this article to the Senate Inquiry in 2011 that the number of sessions was reduced (http://drben.com.au/d/senate2011.jpg). The negative impact of that is twofold: (1) the average number of sessions per person has reduced because there are fewer sessions allowable; and (2) we see fewer new people accessing the program because it now doesn’t offer the level of support they need. I find it confusing to see educated people in the mental health sector ignoring the consistent research finding that ten sessions is inadequate – not an evidence-based level of care. If all of the research and even the advice of the man who invented CBT, cannot change their minds about that fact, then I honestly don’t know what will (http://drben.com.au/docs/Beck_04-03-14.pdf).

Right now in Australia we need sensible and honest assessment of our mental health system. I implore the authors to think about the best interests of everybody, not just their preferred models of care.

“Also ignored is the strong evidence indicating that online therapies can be effective either as an adjunct to, or instead of, face-to-face professional care. While they vary, these online approaches commonly present a course of psychological therapy, structured so the participant can track their progress over time and seek further assistance if their situation deteriorates. They can be critical for reaching traditionally underserviced groups, such as young people.”

Pushing online therapies.

No declaration(s) of conflict of interest?

Professor Hickie is apparently “Passionate about driving evidence-based innovations in mental health care, including new e-healthcare service systems, He is the Chief Scientific Advisor to, and an equity shareholder in, Innowell. Innowell has been formed by the University of Sydney and PwC to deliver the $30m Australian Government-funded ‘Project Synergy’. Project Synergy is a three year program for the transformation of mental health services through the use of innovative technologies” http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/people/academics/profiles/ian.hickie.php

Equity shareholder in technology that he is aggressively promoting in every interview he gives.

Contrast that with the basic therapeutic relationship that is formed by two human beings in a room. We all know, from solid research, that it is the therapeutic relationship that makes therapy effective. Not equity or shares in e-healthcare service systems.

“Their service model focuses on an individual client attending the offices of an individual health professional. Medicare reimburses the health professional on a fee-for-service basis, with typically some additional out-of-pocket cost also payable by individuals to their treating professional.”

Yes? I don’t see Prof Hickie an Dr Rosenberg putting forward the same negative arguments against access to psychiatric consultations under Medicare. Why keep criticising and limiting access to psychology and allied health consultations? Vested interests in the dominance of psychiatry?

What do Prof Hickie and Dr Rosenberg have to say about the individual client attending the offices of the individual psychiatrist? Eg:

“Professional attendance of more than 45 minutes in duration by a consultant physician in the practice of his or her speciality of psychiatry following referral of the patient to him or her by a referring practitioner-an attendance at consulting rooms if the patient:

(a) is a new patient for this consultant psychiatrist; or

(b) has not received a professional attendance from this consultant psychiatrist in the preceding 24 months;

other than attendance on a patient in relation to whom this item, item 297 or 299, or any of items 300 to 346, 353 to 358 and 361 to 370, has applied in the preceding 24 months

Fee: $264.20 Benefit: 75% = $198.15 85% = $224.60 ”

Compare the psychiatry rebate of $244.60 for 45+ minutes to the psychology rebate of $84.80 for 50+ minutes. in the offices of individual professionals.

Is it OK to continue to provide this high level of public funding for individual psychiatry services? If yes, why and on what basis? What makes individual psychiatry services acceptable and reasonable and worth so much more? Have they been evaluated? No, they have not. Better Access has.

Come on, we’ve had enough of these two’s negative and disrespectful opinions about other professions’ services. Let’s hear them pontificate about why we should continue to fund psychiatry at such high levels and without formal evaluation. Now there’s an interesting topic I’d like to hear their opinions about.

Actually, I’d like to see psychologists and social workers being interviewed about their opinions about psychiatry services. Now that would be something new and certainly worth hearing and/or reading.

Team based, collaborative care. There are so many psychologists who operate CURRENTLY in this model with many including myself working out of medical centres along side GP’s, nurses, dieticians, physiotherapist etc and even psychology practices not operating in a medical centre have group practices which include social workers, occupational therapists etc. why is this fact being misrepresented? Psychologists are burdened with having to write reports and letters to doctors and other professionals unpaid, Attend case conferences and attend to phone calls unpaid. Psychologists making a fortune is a myth, we actually represent excellent value for money. Bulkbilling registered psychologists receive $84.80 via the MBS rebate, which after room hire and business expenses translates to an hourly rate of $30! And I can supply the evidence on this. The rebate has not increased in 5 years by the way and more psychologists are being faced with having to charge more gap fees to stay afloat. Many more psychologists would be willing to bulkbill and work in more regional areas but the Medicare rebate system doesn’t financially support this. A simple solution, make the rebate able to sustain bulkbill practices in all regions of Australia.

As for online so called e therapies and resources, whilst there is role for these, there are already a proliferation of websites, YouTube videos posting motivational talks etc all accessible free on online . I actively encourage clients to utilise these and can be helpful, however, the power of the therapeutic relationship cannot be created with someone in deep, emotional pain staring at a computer screen, it comes from human connection, feeling human presence and teary client eyes looking into the eyes of someone who has compassion and humanity. Similarly, seeing a beaming face when positive healing and growth is reported and celebrated, these things occur in therapy rooms everywhere.

For too long the same voices of academics and attention seekers and those with other agendas are being heard at the expense of those of us who work at the coal face and deal with clients on a daily basis and who hand out plenty of tissues, worksheets, guidance but more importantly, authentic human connection.

and the proof of psychiatric drug treatment is? and the cost of psychiatric drug treatment is? Talk about vested interests criticising non-drug options (which is actually what the Australian public wants- less drugs, more psychology). These people are neither expert, nor independent (look at their drug company links).

It would be nice to have a diagnosis of why the system does not deliver (and there is plenty of evidence for its ineffectiveness), before prescribing a strategy to fix the problem. Its always the same story – give us more resources and no demands for accountability. But with each increase in government funding the problem is still the same – and the solution remains the same – give us more resources.

Wow what an obviously bias attack on Medicare accessible therapy. That these 2 psychiatrists have their own vested interests and pull figures out of hats based on little evidence says a lot. It’s election time these guys continuously orchestrate attacks to divert funds from a system that serves millions and which the public love. That they successfully lobbied to cut those sessions down to 10 sessions again based on manipulating data says it all.

I think the above article is a massive oversimplification of a complex problem. To write off a system on the basis of what I suspect are very imprecise measurements of those accessing mental health treatment and those benefiting from it is dangerously misrepresentative and I suspect speaks to other less obvious agendas. If we are simply measuring the overall changes in mental health, similar observations could be made of psychiatry – I note that there are no figures given for the amount spent on psychiatric treatment every year ad relative success/failures – similarly what are the figures for those taking psychiatric medications.

Psychiatry and mental health are not exact sciences. In order to assist the psychiatric team in treating patients there exists guidelines for diagnostic criteria that have been accepted worldwide. I have grievances with the current mental health system where indiscriminate labelling of normal emotional reactions can be used to harm the patient. The coverup and corruption of the deliberate mislabelling that I have witnessed is extensive and diverted important resources away from those who need it most. Whilst the Royal Commission does need to review the services provided to those in need, I also feel that it is just as important to review the processes when the treating team is allowed to harm a normal individual by simply mislabelling the patient and then covering up the mistakes to prevent legal action occurring.