I USED to joke to colleagues, in about 2008, that I quite fancied getting an “EACH” package. I didn’t really know what an “EACH” was exactly, but from listening to the physiotherapists and others, it sounded a terrific way of getting someone to do my cleaning.

Jokes aside, it was around that time I was painfully introduced to the acronyms and processes that make up “community aged care” in Australia. I became increasingly aware of enigmatic entities such as CACP (community aged care package), HACC (home and community care) and ACAT (aged care assessment team). Despite profound interest in older people, I didn’t know what any of this stuff meant, and in honesty, I spent years embarrassingly ignorant on the topic.

To make matters trickier, trying to nail an understanding of aged care in the community is like shooting at a moving target – because as terms and processes are seemingly embedded, they change. Acronyms such as EACH, CACP and HACC are now redundant, having been replaced with new labels, although the underlying concepts haven’t changed much.

The story of community aged care is basically a journey of six parts.

In this article, I will go through the first five of these, and cover how components of it work – at least in theory. In the second part, I will then cover the sixth part – the dreaded “queue”, where patients wait long periods for Home Care Packages (HCPs) – and I will cover the broader (current and future) problems with the community aged care system.

Let’s dive into the parts of the community aged care journey.

1. The population in question.

The aged care system is designed to provide disabled, dependent older people with access to services they may need. Here we will focus only on community care, not on residential “nursing home” care.

As previously written, disability and dependency denote that an older person either cannot or will not complete everyday functional tasks in a manner which is 100% safe – so much so that other people start to become increasingly concerned for their welfare (often family, doctors, neighbours).

As examples, dependent people may struggle to take medications safely or remain adherent to their pills (risking poisoning or illness decompensation); they may struggle to complete the surprisingly complex task of meal preparation (risking malnutrition, food poisoning, fires on stovetops etc); they may try to climb ladders shortly after being discharged from hospital (risking life and limb), and so on.

Many such patients live alone or are not under 24/7 supervision. The risky times for a crisis are when nobody else is around – including at night, or when a cohabitant is at work. Upwards of 25% of older people live alone – and this exceeds 40% in older women aged 85 years or older. Relatives and friends may have an anxious “ticking time bomb” feeling regarding older people when they are alone, especially if an increasing back catalogue of mishaps has built-up over time – such as dramas with pills, unwitnessed falls, wandering outside, failing to eat, or succumbing to scammers.

- The helpers

Given the number of such disabled people in the community, there are more than 1500 companies or organisations called “service providers” who offer home help across Australia. In the past, there were far fewer than this, and many were effectively part of local or state governments.

The variety of services available for purchase spans more than a dozen categories (here, pages 15–17):

- nursing – a community nurse can visit the older person (wound care, medication giving etc);

- personal assistance – carers helping with dressing, showering etc;

- allied health – access to help from a swathe of therapists from occupational therapy and psychology, through to hydrotherapy or social work;

- home modifications – such as installing rails and shower chairs;

- domestic assistance – house cleaning and linen services;

- home maintenance – home repairs and gardening;

- equipment – from mobility frames, hearing and visual aids, through to car modifications;

- transportation – for instance, being directly driven by volunteers, or provided with taxi vouchers;

- meals – either brought into the home, or provided at a centre;

- training and preparation of food for meals – to enable ongoing self-initiation of cooking;

- one on one companionship or support – a carer visits or phones the older person and/or takes them to shops;

- group social support – for example, linking with Men’s Shed or community social outings; and

- linking to specialist organisations – such as continence clinics or service dogs.

There is certainly a lot to choose from at the metaphorical “home care services” shop.

- The funds (in theory)

In theory, service-providing companies can offer whatever specific support an older person needs, from injecting insulin to hanging out the laundry, but naturally, they need to be paid for their work. Currently, the going rate for home services on normal weekdays sits between $50–120 per hour (see examples here, here, here, here and here). Consequently, given older people may need visits every day, the cost of remaining at home with external support can sometimes hit hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars every week – which few can afford. Accordingly, the Commonwealth government specifically is (these days) responsible for maintaining buckets of money via which they pay service providers on behalf of older citizens – or at least to pay the majority of the costs per person (older clients pay a smallish copayment into the mix, explained below).

For many years, crudely, there have been two sorts of funding pools.

Theoretically, one type pays for lower acuity services, aimed at mildly disabled older people, and costs the government a relatively small amount; the other bankrolls higher acuity services aimed at more profoundly dependent people, such that they receive relatively greater funds over time.

The first type of fund is currently named CHSP (Commonwealth Home Support Program). Up until 2015, a broadly similar pool of money – though partly managed by states, not the Commonwealth – was known as HACC.

If an older person today is approved to access CHSP, the crux of what they actually get is a heavily discounted price for individual services, compared with what they would otherwise pay if the same service was privately sourced. The way this is achieved is that the Commonwealth government pays service providers’ annual “grants” or “block funds” for their work; overall, such government to provider grants (hopefully) cover the majority of the running costs and overheads. A total of $1.76 billion was given to the hundreds of CHSP providers via grants in 2017–18, most commonly in lump sums under $500 000.

Service providing organisations then ask their CHSP clients to pay a smallish contribution to the total (on top of their government grants). However, there is no uniform or set amount currently, and no means testing. Averaged out across Australia, older clients pay for about 10% of the cost of CHSP services; the Commonwealth thus subsidises 90% of the cost on their behalf. Clients are often asked to pay about $5 or $15 for a service, meaning, for example, that it might cost an older person $10–$30 each week to have someone help do their shopping for 2 hours. This same service may cost upwards of $50–$100 if sought as a private enterprise.

How much is the Commonwealth paying to care providers on behalf of its citizens using the CHSP funding pool? Dividing the total grant money given to CHSP providers by the more than 800 000 clients using their services last year, the government pays service providers an average of around $2800 per CHSP client each year. This is cheap in context – as will be shown below.

The second, but higher level funding pool is currently called the HCPP (Home Care Package Program). Patients are able to get one of four (more substantial) quantities or “packages” of money to put towards community aged care. The amounts increase depending on the degree of disability. So-called Level 1 and Level 2 funding quantities are aimed at patients who have moderate degrees of disability; years ago, the equivalent were CACP packages. Meanwhile, Level 3 and Level 4 packages are designed for those more severely in need; these were formerly known as EACH packages. The current amounts of money for each Home Care Package are:

- Level 1 = $8750 per annum (note this is three times more funding than the average CHSP client, even at Level 1)

- Level 2 = $15 250 per annum

- Level 3 = $33 500 per annum

- Level 4 = $50 750 per annum

How much do patients themselves have to pay as a “contribution” fee? Patients may be asked to pay a combination of a so-called daily basic fee of around $10 per day, plus (maybe) an added fee as high as $30 per day, depending on a financial (income) means test by Centrelink.

One additional feature of the HCP scheme is that, given it theoretically caters for more complicated cases, patients can purchase an additional type of service from the participating providers – namely “case coordination” or “case management”. This can be quite expensive, and is not available through the CHSP stream.

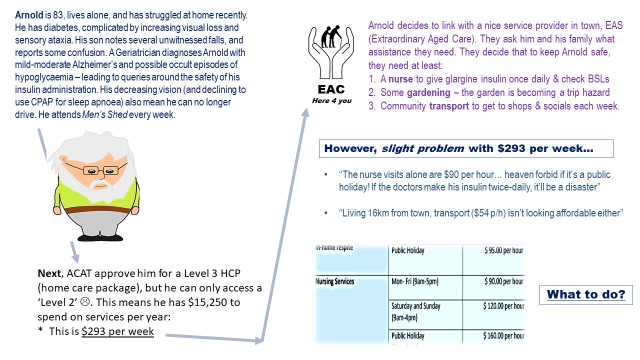

The figure below shows how, despite what appears to be a large amount of money within an HCP, this can be consumed quickly and may not always cover an older person’s needs.

Figure 1. A case study illustrates the difficulty faced by older people when trying to access community services, in terms of budgeting. Informal and unpaid supports from family and friends is typically enlisted – if available – to fill in the gaps. Patients may also use money from their pension or other income, to add external services if these are essential.

- The portal – getting a foot in the door when aged care is needed

Nationally, since late 2015, if someone has held concerns about an older person’s safety at home, there has been a single phone number and webpage through which they can lodge their desire to seek formal external help: My Aged Care (MAC). Its running is outsourced to Health Direct, it has two offices nationally (Box Hill in Victoria, and the Gold Coast in Queensland), and it receives more than 1.4 million phone calls per year.

Let’s imagine a concerned niece refers her increasingly forgetful and immobile uncle via the MAC website, because she is concerned he is muddling his medication and isn’t eating. Screening the case using a nationally consistent form, staff within MAC then effectively make a binary triage decision (however tricky this sounds): namely, whether the uncle falls into a lower or higher level of need. They then channel him into one of two streams or pathways, both of which ultimately lead to a face to face assessment by an external clinician or assessor.

- The initial assessment and the golden ticket

To connect dependent older people to the Commonwealth funds, which, in turn, pay service providers on their behalf, an initial visit is teed up by MAC so that the older person can be assessed. One of two teams will be sent, each connected to one of the two mentioned funding pools:

- If MAC feels the patient needs are low or mild, they send an assessor from a service called the RAS (regional assessment service). A RAS assessor will typically visit the person at their home. RAS is associated with the CHSP funding pool.

- If MAC feels the care needs are more substantial, they instead send a more comprehensive assessor from the local ACAT (aged care assessment team). Again, an ACAT assessor – commonly a nurse or an allied health professional – may conduct a home visit. ACAT is associated with the HCPP funding pool.

Notwithstanding, the overarching purpose of these face-to-face meetings with the older person is to assess the severity and “flavour” of their disability, and to rubber stamp that the case is legitimate from the perspective of the fund-managing federal government. The assessor will generate a report – akin to a “golden ticket” – which approves the patient for access to government funding, in turn to purchase whatever services appear to be needed. The RAS or ACAT report is the gateway to accessing Commonwealth money to purchase care required – it is also known as the client’s “support plan”.

If a patient is approved for a particular type of service by a RAS assessor (say, domestic assistance), they can either refer the older person to preferred local agencies there and then, or alternatively, generate something called a “referral code”. The latter is a long number that older clients can wield if calling aged care providers themselves – it codes for “I am formally approved to receive domestic assistance, can you help me?” If a more complex patient was instead assessed by ACAT, the assessor may simply generate a referral code for, say, HCP, Level 3. It is these referral codes that give the patient the power of a golden ticket, so to speak, when hunting for a care provider.

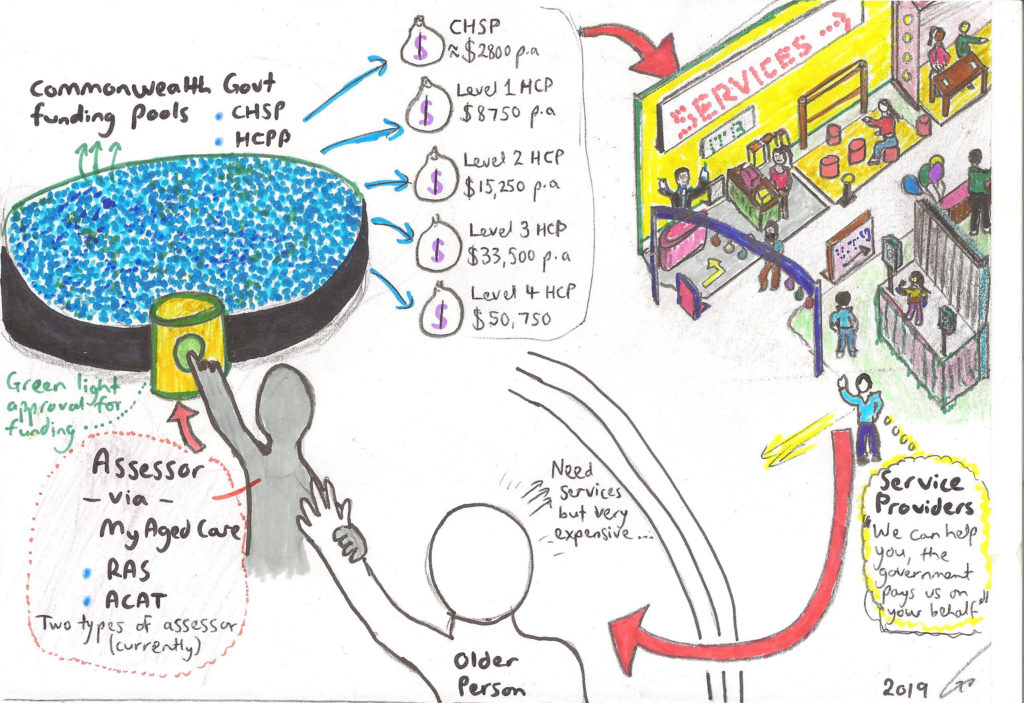

With this in mind, the processes can be simplistically summarised as follows:

Figure 2. A summary of the loop via which the CHSP and HCP federal government funding pools are paid to service providing organisations in Australia in late 2019, on behalf of older people. Note that patients typically pay 5–10% of the total cost of services they seek as a contribution. Acronyms and processes may change in the future!

- The wait for a Home Care Package

In general terms, access to CHSP level services often occurs quite quickly following a RAS assessment. However, it is no secret that the wait for an HCP can be extraordinarily prolonged. This topic – the fate of patients after they’ve had on-paper approval for a certain level of funding for higher level community services – warrants a whole essay of its own.

Accordingly, part 2 of this series will cover that issue and more. In the meantime, it would be interesting to read your thoughts in the comments: what problems have you faced in reality when dealing with the community aged care system?

Dr Toby Commerford is a consultant geriatrician at Royal Adelaide Hospital, is course coordinator for geriatrics at the University of Adelaide’s Rural School, and practises remote and rural outreaches to Port Augusta and Murray Mallee. He is also the RACP representative on the classifications clinical advisory group to IHPA (independent hospital pricing authority), and is the lead singer in a rock band. He can be found on Twitter @TobyGerisMusic.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

really useful article, thank you so much for breaking down what is a hard topic to get your head around

You’ve managed to put all the necessary information together so succinctly and clearly. Very helpful. Thank you

A great summary of a complex area. Look forward to part 2!

Greatly appreciated this succinct synopsis of a minefield of information that is difficult to access, analyze and comprehend efficiencies and effectiveness. Thank you very much. Looking forward to next instalment.

An excellent, concise paper, finally addressing both the health and confusing financial needs of the elderly. Looking forward to Part 2.

Absolutely B$#*^dy Fabulous.

I, like you, despair at the anagrams not to mention the bureaucracy.

I am writing a book for Hachette entitled ” It Aint Over till its Over” .

Would you be prepared to be in it?

Got to have it in end December.

May we chat?

Dr John D’Arcy O’Donnell

0418248269

The best article I have ever read on aged care assessment and funding, thank you so much.

Really useful article thank you. Awaiting part 2 eagerly.