BY the time Australian children start school, research has demonstrated two clear issues: high rates of preventable health and developmental problems, and clear inequities already evident in health and developmental outcomes.

Inequities are differential health outcomes that are largely unnecessary, unacceptable and potentially preventable. Inequities that emerge in early childhood track forward to adulthood in terms of higher rates of mortality and physical, social and cognitive morbidity as you move down the social gradient. These inequities constitute a significant but preventable public health problem, and a platform for intervention that aligns with one of the Australian Government’s Science and Research Priorities: to deliver “better models of health care and services that improve outcomes, reduce disparities for disadvantaged and vulnerable groups, increase efficiency and provide greater value for a given expenditure”. Addressing inequities early in life has the potential to fundamentally change children’s chances and create a healthier and more productive future adult population.

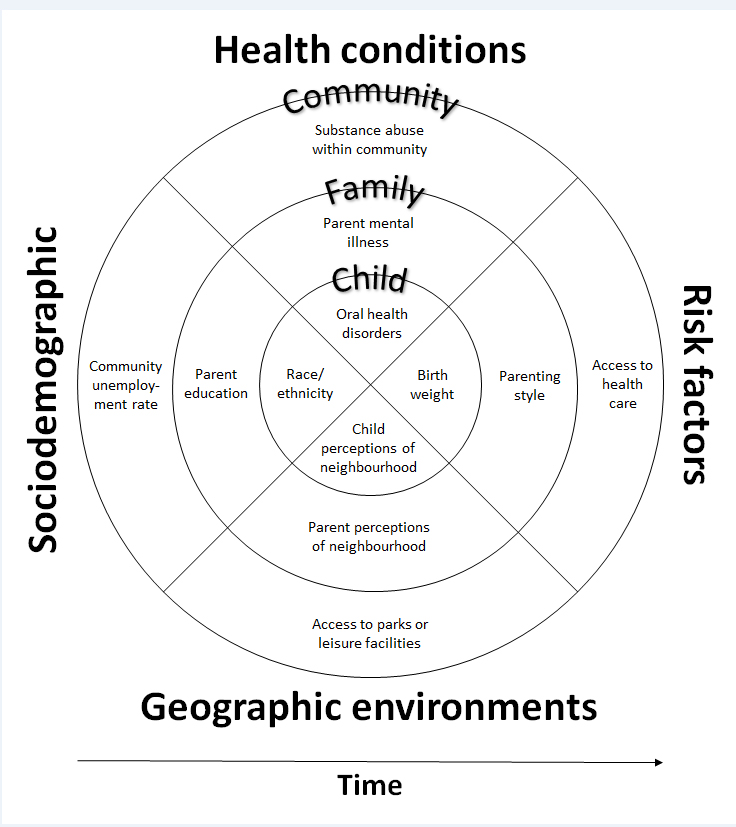

A social determinants approach to dealing with disadvantage includes the settings in which children develop as a framework for addressing inequities (Figure 1). Sources of disadvantage may therefore be identified and potentially addressed at the individual (eg, poor nutrition), family (eg, low parent education) and/or community level (eg, services, neighbourhoods).

Figure 1 – Framework of child disadvantage aligning a social determinants and bioecological perspective

In order to address these inequities through effective interventions, we need a clear understanding of the modifiable determinants in their causal pathways. Finding and testing leverage points for change that are modifiable and have effects at the population level could begin to close the gap. Within these social determinants, there are tangible and proximal solutions within our existing service systems that could be addressing inequity but instead may actually be driving it.

Health care opportunities and challenges

The Australian health care system is an important service delivery platform to deal with child health inequities, within which there are a range of designs and financing conditions. For young children (< 5 years of age), available health care includes not only community-based systems such as primary care (eg, GPs), community health and specialist care (eg, paediatricians) but also nurse-delivered universal maternal or child and family health services. Care is free to families, provided by qualified nurses and based on prevention and early intervention. Delivered with varying frequency in almost every Australian state and territory, this platform provides the basis for proportionate universal health care delivery (ie, offering universal services, with a level and intensity based on need). Research has shown public support for vertical equity investments, providing more health care funding to people with greater needs, especially for vulnerable children in Australia.

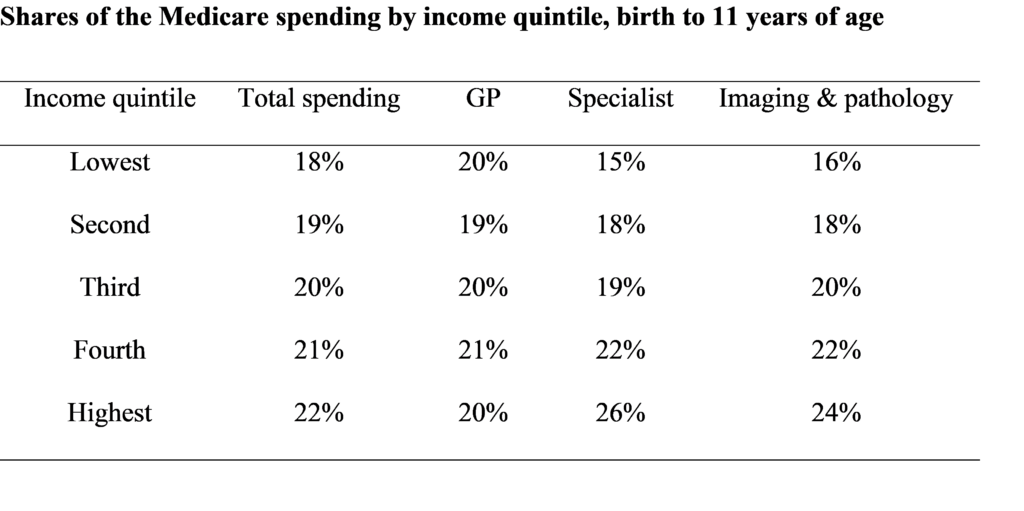

Recent research has also highlighted some of the barriers and inequalities that exist more specifically in secondary or specialist care for children in Australia. For parents accessing specialist services, Medicare pays a set schedule free. Doctors may choose to accept this fee and bulk bill or may choose to also charge a patient out-of-pocket cost. For children, specialist bulk billing is only 30–42%, with the average out-of-pocket charge for paediatricians of $128 for an initial consult (here and here). This poses a barrier to care for some of our most vulnerable children; Medicare is not equitable for Australian children. Those from poorer households receive less funding after controlling for the health needs of children (Table 1). Inequality was strongest during the first year of life and for specialist care.

Creating equitable system change: what can we do differently now?

Intervening early can produce positive and sustained effects on children’s outcomes, in particular for children from disadvantaged families (here and here). A number of interventions such as antenatal care, nurse home visiting, early childhood education and care, parenting programs, and the early years of school show a positive effect when each has been evaluated as a single strategy intervention on specific aspects of child development or behaviour at a specific point in time.

There is emerging interest in the potential of “stacking” interventions in early childhood both simultaneously and sequentially over time (here and here). It has been emphasised that “continuity” (timing, duration, and quality content of child health and development services) as well as “complementarity” (different types of services with diverse focus and target groups) of services are necessary to promote human capital. Targeting multiple health and educational interventions in early childhood, therefore, may exceed that of a single intervention strategy. This potential “added benefit” to children who have access to more evidence-based services throughout early childhood offers important new directions for research and policy.

Creating metrics that inform system change

To drive system change, we need metrics that both expose the gaps and deliver evidence-based opportunities for prioritising policy and practice effort and investment. Adaptive system metrics move us away from outcome indicators toward a set of evidence-based process indicators that can inform change around the equity “triple bottom line”:

Quality: Are the strategies delivered effectively, relative to evidence-based performance standards? A strategy with quality is one for which there is robust evidence showing it delivers the desired outcomes. A large number of research studies have explored aspects of this question (ie, “what works?”). As such, we should pay particular attention to the quality dimension.

Quantity: Are the strategies available locally in sufficient quantity for the target population? Quantity helps us determine the quantum of effort and infrastructure needed to deliver the strategy adequately for a given population.

Participation: Do the appropriately targeted children and families participate at the right dosage levels? Participation shows us what portion of the relevant groups are exposed to the strategy at the level required to generate the desired benefit (eg, attending the required number of antenatal visits during pregnancy). Participation levels can be calculated whether the strategy is universal or targeted.

These ideas are highlighted in the Royal Australasian College of Physicians position statement on inequities in child health, with specific references to both national and organisational reporting on inequities. Indeed, there is a special call to health care practitioners to consider whether their own practice should include measures such as social prescribing, and challenge organisations to consider whether their own equity metrics regarding access and utilisation are actually addressing inequity locally.

Innovative models of care: doing better within existing health care

There are opportunities right now to test innovative primary care models. For example, we are testing an integrated model of care that brings paediatric expertise to GPs working in lower socio-economic areas so that they can deliver the right care at the right time to children facing disadvantage (to be presented at the International Conference on Integrated Care in Spain on 1–3 April 2019).

In universal maternal, family and child health care systems, we have tested the effectiveness of sustained nurse home visiting – delivering evidence-based preventive care through existing services to families facing disadvantage – showing we can make a difference to family and child wellbeing through our existing universal platforms, and actually deliver on the idea of proportionate universalism.

Is equity possible?

There are at least two stellar examples in Australia in which health care policy and processes have converged to drive more equitable outcomes: 5-year survival rates for leukaemia and rates of fully immunised 2-year-olds (90.7% in 2015–2016). Five-year relative survival for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia increased by 17 percentage points between the periods 1983–1989 and 2004–2010 (from 73% to 90%) with a long running absence of socio-economic inequity in Australia (here and here).

For both examples, there was a high moral imperative and clear benefit, evidence-based agreed care, systematic data collection and reporting, and health care system incentives to drive reach, together with workforce innovation. In both cases, innovation has driven solutions that have overcome service inequities, including cost of access to specialist paediatric specialists, and rural and remote barriers to interventions.

These purposeful and repeatable aspects of health care would suggest that we could be doing much better within our existing system, driving us toward equitable care that can deliver better and more equal outcomes for Australia’s children. And we could do it now.

Professor Sharon Goldfeld is a paediatrician and Deputy Director, Centre for Community Child Health the Royal Children’s Hospital and National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellow and Co-Group leader of Child Health Policy, Equity and Translation at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

Professor Harriet Hiscock is Associate Director of Research at the Centre for Community Child Health, Consultant Paediatrician and National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellow. She is Director of the Royal Children’s Hospital Health Services Research Unit and Group Leader of the Health Services research group at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, where she focuses on improving mental health services for children.

Associate Professor Kim Dalziel is Deputy Director of the Health Economics Unit, Centre for Health Policy at the University of Melbourne. She is also a Team Leader with the Health Services research group at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless that is so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Aboriginal Primary Health care organisations are another example of best practice in delivering culturally appropriate care to extremely disadvantaged families. https://portal.sahmriresearch.org/en/publications/the-australian-nurse-family-partnership-program-for-aboriginal-mo