TRANSGENDER men and women have been “invisible” in health datasets, say researchers who have found key differences in the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) between transgender and cisgender people.

Researchers reported in this week’s MJA that, among people attending sexual health clinics, transgender women were more likely to have an STI than cisgender heterosexual patients (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.56; 95% CI, 1.16–2.10; P = 0.003), while transgender men were as likely as cisgender gay and bisexual men to have an STI (aOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.46–1.13; P = 0.16).

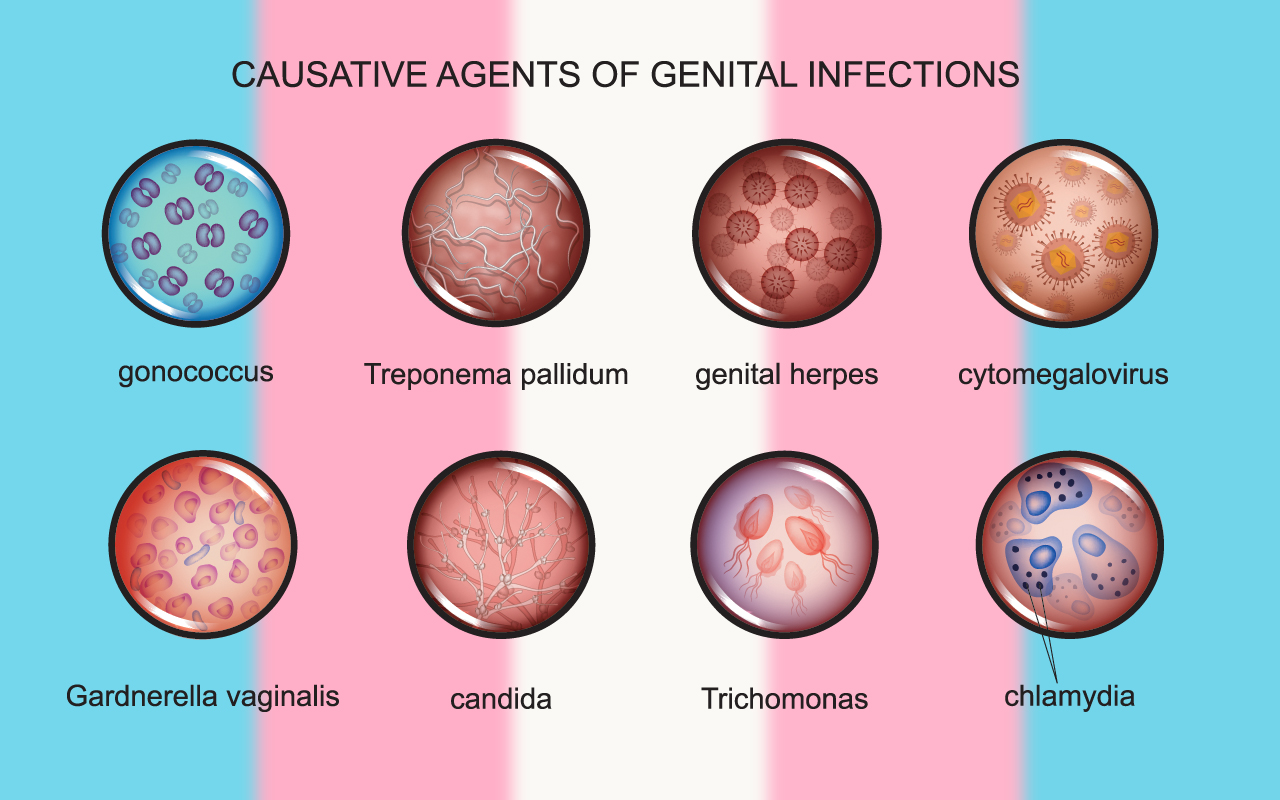

They also found that the rate of gonorrhoea test positivity among transgender women had more than tripled over the 8-year study period (2010–2017), increasing from 3% to almost 10%.

For the study, the researchers analysed the data of 1260 transgender people (404 men, 492 women and 364 unrecorded gender), 78 108 cisgender gay and bisexual men, and 309 740 cisgender heterosexual people who attended 46 sexual health clinics across Australia, at their first visit.

Study co-author Mr Teddy Cook, Manager of Trans and Gender Diverse Health Equity at ACON, said the analysis showed that there was a group of people in Australia who were “completely invisible” in health data.

“Part of the reason why it’s so important to make sure we capture trans and gender-diverse people accurately and meaningfully, is that the trans experience has often been misunderstood as being a gender identity in and of itself. That is why we see this ‘male, female or transgender’ data collection option, when really, most trans people are just male or female. One of the really big gaps that we found in this process was that non-binary people are completely erased,” Mr Cook said in an exclusive MJA podcast.

“This analysis shows a third of the sample were men, a third were women and then another third really couldn’t be further classified in terms of their gender and then couldn’t be analysed.”

Dr Fiona Bisshop, a GP who specialises in transgender hormone therapy and transgender-affirming medical care as well as sexual health and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) management, said there had been “a huge hole” in the research relating to STIs in transgender and gender-diverse Australians.

“We have very poor methods of identifying people’s gender and trans and gender-diverse status,” said Dr Bisshop, who is on the Board of the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health (AusPATH).

“A lot of collection forms don’t even ask [beyond male or female], or they just ask if someone is transgender, and that’s not enough.”

Dr Bisshop said non-binary and gender queer people often “slip through the net completely”.

“This is the first time that we have seen this kind of big dataset for this group of people and that’s very telling,” she said, noting that there were also many transgender and gender-diverse people with STIs who did not attend sexual health clinics, and they would be missing from these data.

Mr Cook said a more accurate way to collect data on transgender and gender-diverse people would be to ask two simple questions: “what gender were you assigned at birth?” and “what gender do you identify with now?”

“That just shows every variety of trans person and every variety of cisgender person as well,” he said.

Research co-author Dr Denton Callander, of the Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, and the New York University School of Medicine, said in the podcast that the MJA findings were among many to suggest that trans and gender-diverse people had unique needs in terms of STIs.

“If you are trying to understand how to help people prevent and manage HIV and other STIs, you need to understand what the risks are and this highlights that collapsing them into a third, single category is not only methodologically indefensible, but it undermines our public health efforts.”

Dr Bisshop said the findings underlined the importance of not making assumptions about patients’ sexual practices based on their anatomy or their gender.

“It’s so important to be able to have a doctorpatient relationship where [a patient] can feel comfortable [giving their] sexual history without it being seen as voyeuristic or intrusive,” Dr Bisshop said. “It’s different when they are going to a sexual health clinic because they are expecting to be asked these sorts of questions, but in a general practice setting, you need to have that good relationship before you can start going there.”

However, positive experiences in health settings remained elusive for a significant proportion of transgender and gender-diverse Australians, according to a survey presented at the Australasian HIV and AIDS Conference.

The survey of about 1600 transgender and gender-diverse people found that less than 50% of respondents felt that they received sexual health care that was sensitive to their individual needs in general practice, and less than 30% received such care in hospitals. Survey respondents also reported that more than 40% of general practice clinical staff and more than 60% of hospital clinical staff made assumptions about their body or sex life. Dr Denton said negative experiences with health professionals “put a bad taste” in the mouths of transgender and gender-diverse people.

“If you don’t feel respected in health care … you are less likely to engage in health care, so that is troubling,” he said.

Dr Bisshop said the way in which transgender people were supported in general practice was mixed.

“Most GPs would like to do better than they do, but they don’t know where to find the resources or they don’t know the resources exist [to assist them],” she said. “We need more studies like this looking at trans and gender diversity. We need to find better ways of identifying their specific health problems, and their situation with respect to STI testing and treatment.”

Dr Bisshop said it was also important to be able to link a patient’s sexual health care with their gender-affirming hormone care.

“If you can have doctors who are prepared to do both, then you are much more likely to have patients who are engaged in care, who will come in for regular screening and their sexual health needs. The best-case scenario would be their GP, then they can form a relationship with them which will lead on to being able to disclose other areas of concern in their lives including their sexual health needs.”

more_vert

more_vert