Recent reports from the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States have described a small number of invasive infections with Mycobacterium chimaera associated with cardiac surgery that have been associated with high mortality. M. chimaera is likely to have been transmitted to patients by aerosols generated from contaminated heater–cooler units used during cardiopulmonary bypass. Here we describe the outbreak and discuss the relevance for Australian clinicians. Our primary objective is to raise awareness locally of this rare but serious health care-associated infection so that patients can be promptly diagnosed and optimally treated.

To formulate an evidence-based overview of the topic, as applied to clinical practice, we conducted a PubMed search of original papers and review articles in the period 2004–2016 using the term “Mycobacterium chimaera”, along with publications released by government agencies, public health bodies and medical device regulatory authorities, and selected conference presentations.

Initial outbreak description

In 2012, clinicians at the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, diagnosed two patients with ultimately fatal infections due to M. chimaera, a member of the M. avium complex (MAC) group of slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria.1,2 The patients — one with prosthetic valve endocarditis and the other with bloodstream infection — had no known direct community or inpatient contact with each other, but had both undergone cardiac surgery with insertion of prosthetic material at the same hospital (in 2008 and 2010).1 Typing suggested that the strains from these two cases were genetically related and were, in addition, distinct from M. chimaera strains isolated from respiratory samples from other patients at the same hospital.

Detection of these two cases of an unusual and fatal infection prompted an outbreak investigation for a potential hospital source.3 Given the propensity of MAC organisms to be found in association with water, the investigation focused on points of contact between water and patients undergoing cardiac surgery. M. chimaera was isolated from the water circuit of five heater–cooler units (HCUs).3 These devices are used during cardiopulmonary bypass to regulate temperatures of extracorporeal blood and cardioplegia solution, and do not have direct contact with patients. When contaminated HCUs were in operation, air samples from the operating theatre itself and its exhaust air flow were also positive for M. chimaera. The authors hypothesised that aerosolised M. chimaera from contaminated HCUs was the source of infection. Subsequent experiments performed in a cardiac operating theatre with an ultraclean laminar airflow system confirmed aerosolisation of M. chimaera from a contaminated HCU and demonstrated smoke dispersal from an HCU to the operative field in 23 seconds when the unit’s airflow was directed towards the operating table.4

In parallel, a case detection exercise identified another four patients with invasive M. chimaera infection at the same hospital, with all six having undergone cardiac surgery with insertion of prosthetic material between August 2009 and March 2012. A nationwide investigation involving the 16 Swiss centres that perform cardiac surgery was mandated by the Federal Office of Public Health in 2014, and this identified eight contaminated HCUs but no further patient cases.5 Swiss authorities made a public announcement about the cluster in July 2014.6

International reports and response, including Australia

After the initial reports from Switzerland, invasive M. chimaera infections following cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass have been reported in the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and the US.7–10 At least 50 cases have been diagnosed worldwide (Professor Hugo Sax, University Hospital Zurich, personal communication). Seventeen probable cases identified in the UK had undergone heart valve repair or replacement in ten National Health Service (NHS) trusts since 2007.9 A nationwide prospective case finding investigation, using a mandatory reporting system, performed in Germany from April 2015 until February 2016 identified five patient cases from three cardiac surgery centres.10 All five patients were exposed to HCUs manufactured by a single manufacturer. M. chimaera was also identified in samples from new machines and the environment at the manufacturing site.10 As a result of this investigation, German public health authorities triggered notifications of a suspected common source for the outbreak via the European Early Warning and Response System and under the World Health Organization International Health Regulations framework.10

Public Health England coordinated testing of 24 HCUs (LivaNova [formerly Sorin Group]); also the manufacturer of the devices used in Zurich) at five NHS trusts.9 M. chimaera was culturable from water sampled from 15 of the units, and from surrounding air for about a third of the devices while they were running.9 The manufacturer issued a field safety notice in June 2015 identifying the risk of contamination by bacteria and subsequent aerosolisation during operation (http://www.livanova.sorin.com/products/cardiac-surgery/perfusion/hlm/3t). The notice recommended enhanced disinfection with updated instructions for use including revised recommendations for operation, disinfection and microbial monitoring.

In October 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Communication to raise awareness of the issue of M. chimaera infections associated with HCUs and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidance for health care facilities, health care professionals and patients.11,12 In the context of heightened surveillance, in November 2015 the Pennsylvania Department of Health reported clusters of patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among patients exposed to open heart surgery at two hospitals.13 Whole-genome sequencing of M. chimaera strains from 11 infected patients and five HCUs (Stöckert 3T [LivaNova]) from two US states (Pennsylvania and Iowa) confirmed their genetic relatedness, strongly suggesting “a point-source contamination of Stöckert 3T heater–cooler devices”.14

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) announced an investigation into this issue and released recommendations to health facilities in May 2016.15 In August, the TGA reported one case of possible patient infection with M. chimaera following open cardiac surgery.16 In October, a TGA alert identified the affected product as the Stӧckert 3T HCU, and reported that in Australia “25% of these devices have tested positive for the Mycobacterium chimaera organism or other organisms”, but all positive machines were manufactured before September 2014.17 In keeping with a recent recommendation from the FDA,18 the TGA recommended that health services “consider transitioning away from” 3T devices manufactured before September 2014.17 Ten HCUs from four Western Australian hospitals (of 15 HCUs tested from five hospitals) were colonised by genetically related M. chimaera strains, along with other mycobacteria.19 The M. chimaera strain cultured from a pleural biopsy of a patient who had undergone surgery at one of these hospitals was considered distinct from the HCU strains, suggesting that the HCU was not the source of infection in this case.19 Subsequently, whole-genome sequence comparisons of 43 M. chimaera strains from HCUs in four Australian states and four regions of New Zealand confirmed close genetic relatedness of these strains with those from HCUs in the northern hemisphere.20 Whole-genome sequencing also showed that a patient isolate was identical to an isolate from an HCU used in the facility during the patient’s surgery.20

While there is no clear consensus on how to best manage HCUs to minimise risk, some recommendations have been released.9,12,14,21,22 The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) released national infection control guidance in September 2016, outlining recommended risk mitigation strategies for Australian health service organisations.23 A simple precautionary step is to ensure that HCU ventilation airflow is directed away from the patient and towards the theatre exhaust whenever operational, although it is not clear whether this eliminates risk entirely.4 Other options, at least until M. chimaera contamination is excluded by microbiological testing, include physical removal of HCUs from the operating theatre (to an adjacent room) — as was nationally implemented in the Netherlands8 — or placement of the unit in a custom built sealed container that directs ventilation outflow out of the operating theatre, as described in Zurich.3 The TGA and ACSQHC note that the latter approaches may not be feasible in all facilities and should be planned in discussion with the Australian sponsor of the device to ensure it will not compromise device function.15,23

Clinical description of HCU-related M. chimaera infection

Although the risk of invasive M. chimaera infection following cardiac bypass surgery in Australia is estimated to be very small, the long incubation period and unusual non-specific clinical presentation mean that general practitioners and specialists need to know when to suspect this rare condition and how to diagnose it (Box).

The diagnosis in cases so far has been complicated by long delays between surgery and symptom onset, non-localising clinical presentations, and the need for directed microbiological testing using special tests. The following summary is compiled from existing published reports: six confirmed cases in Switzerland,1,3 which were subsequently reported in combination with three confirmed and one probable case from the Netherlands and Germany,7 five additional confirmed cases in Germany,10 and 17 probable cases in the UK.9

Although the risk of infection appears to relate principally to cardiac bypass procedures involving insertion of prosthetic material, there is one report of infection following coronary artery bypass grafts.10 HCUs are also used during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, but no cases of infection have been attributed to this exposure.9 Establishing the risk of infection among exposed patients is difficult given incomplete data and the possibility that some cases have either been missed or remain in latent phase, but the risk is very low. Public Health England reported that about 100 000 patients underwent valve repair or replacement between 2007 and 2014, and estimated that the incidence rate of M. chimaera infections among these patients was 0.4 (95% CI, 0.2–0.7) per 10 000 person-years of post-operative follow-up.9

The period during which patients underwent initial cardiac surgery extends from 2007 to 2013.7,9 According to Haller and colleagues,10 the manufacturer involved in their investigation confirmed that HCUs delivered before mid-August 2014 may have been contaminated with M. chimaera. The latent period from cardiac surgery to diagnosis has ranged from 3 months to 5 years (median, 19 months among UK patients).9,10 Among the 15 European patients, median age was 63 (range, neonate to 80 years) and 14 were male.7,10 Patients have not, in general, been significantly immunocompromised.

Patients have presented with endocarditis or other cardiac infection, disseminated or non-cardiac infection, and surgical site infection.3,7,9 Fourteen of 15 European cases had cardiac infection: endocarditis, prosthetic valve infection, paravalvular abscess, graft infection and one case of myocarditis. In many cases, however, initial presentation was with non-cardiac disease: bone infection (osteoarthritis, spondylodiscitis), cholestatic hepatitis, nephritis or surgical site infection. Other manifestations included splenomegaly, ocular disease (panuveitis or chorioretinitis), and mycobacterial saphenous vein donor site infection.7 Of 13 probable cases in the UK with clinical description, six presented as cardiac infection, five as disseminated or non-cardiac infection, and two as surgical site infection. Several patients have been misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis or connective tissue disease, and commenced on corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.1,7,24

Diagnosis of M. chimaera infection requires directed investigations. Public Health England has recommended that patients with endocarditis and/or disseminated infection should undergo mycobacterial culture and molecular testing (16S rRNA gene sequencing) of tissue samples and three sets of mycobacterial blood cultures in addition to routine diagnostics.9 Patients with wound infections unresponsive to routine antibiotic therapy require tissue or bone samples to make the diagnosis rather than swabs.9 To permit harmonised assessment of patients who have previously presented with a syndrome that may be consistent with M. chimaera infection related to HCU exposure, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has produced definitions for retrospective identification of probable and confirmed cases.22

Antimicrobial therapy has centred on combination treatment with clarithromycin, rifabutin and ethambutol, with the addition of fluoroquinolone or amikacin in some cases.3,7 Clinicians involved proposed that initial antimicrobial therapy to reduce the burden of infection should be followed by surgical intervention followed by further antimicrobial therapy.5 Serial fundoscopy to monitor chorioretinitis may be a useful tool to monitor response to therapy.3 Nine of 17 patients in the UK died.9 Six of 15 European patients with confirmed or probable infection died.7,10 In four cases reported by Kohler and colleagues,7 death was attributed to uncontrolled M. chimaera infection despite directed therapy (15–375 days).7 Three patients were being monitored following completion of treatment at the time of reporting.

In Australia, when a patient case of M. chimaera infection is confirmed or an HCU is found to be contaminated, this should be reported to the relevant hospital infection control team, the jurisdictional health department, the TGA Incident Reporting and Investigation Scheme, and the Australian distributor of the affected unit(s).

Summary

There is an evolving international outbreak of M. chimaera infection associated with contaminated HCUs used for cardiac bypass surgery. While the risk to exposed patients is very low, cases are challenging to detect and associated with high mortality. Diagnosis requires an awareness of this possibility among clinicians and microbiologists, particularly when evaluating patients presenting with one or more of sternal wound infection or mediastinitis, prosthetic valve endocarditis, early prosthetic valve failure or systemic inflammatory condition. Further, these complications may present months or years after a bypass procedure. A first case has been identified in Australia, and we must remain vigilant in order to detect and manage any further cases.

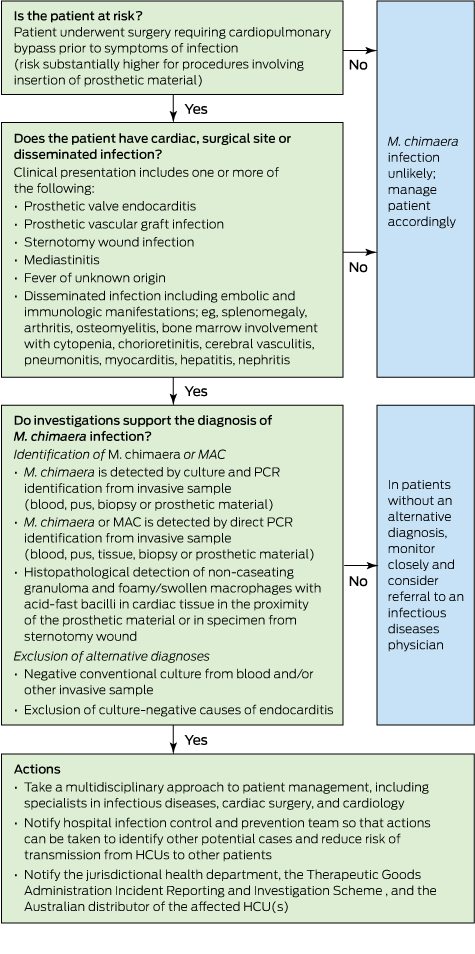

Box –

Proposed flow chart for evaluating patients with suspected heater–cooler unit (HCU)-associated Mycobacterium chimaera infection

more_vert

more_vert