Australia’s primary mental health system requires some major changes to the way people access more specialised psychological care, write Dr Sebastian Rosenberg, Professor Ian Hickie and Dr Frank Iorfino.

What does comprehensive primary mental health care reform look like? What would it mean for consumers, health professionals, service providers, planners and funders?

We have previously outlined a framework for reform. It is now possible to describe the components and pathways of a new primary mental health care ecosystem, drawing on our research into data collection, digital systems and policy reform.

This is timely. The federal government must decide how it will respond to the recent evaluation of the Better Access Program. GPs are concerned about survival, Medicare rebates, and asserting a role as expert generalists. Psychologists focus on session limits, responding to needs of people for whom the Program was never intended. People still wait too long to find the right mental health care.

The problems extend beyond Medicare, with 60 000 thousand people receiving some sort of mental health care under the National Disability Insurance Scheme, presumably aimed at their functional rather than clinical recovery, at a cost of $2 billion in 2021.

The broader task of reform

Although these narrower perspectives drive the public debate, the task of broader primary mental health care reform is undone.

Overcoming inequity and improving the quality of mental health care cannot be achieved by existing workforce and service models alone.

Funds to just grow the workforce or to increase service access for particular groups of people will not be enough.

This comprehensive primary mental health ecosystem will require national investment and depends on the delivery of several key functions.

Reassuringly, many of these have already been evaluated as effective, though often then defunded.

Legacy of acute fragmentation

First, we must recognise and respond to the legacy of acute fragmentation which afflicts the system.

In fact, use of the term “system” belies the fact that federal- and state-funded services are rarely planned together and regularly lack data or other connections.

This is perfect environment for Australians who require primary mental health care to “fall through the cracks”. And these gaps have consequences.

Australians with mental illness have notably lower life expectancy, often dying of chronic illnesses that could have been managed in primary care.

Transferring more functions to Primary Health Networks

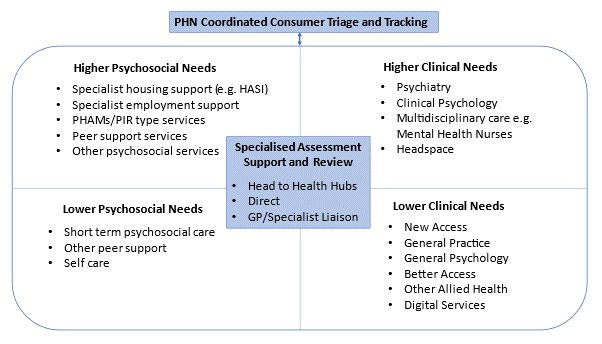

By contrast with the existing GP-based gatekeeper system, it may be desirable to transfer the essential triage function to Primary Health Networks (PHNs), proposing that regionally organised authorities are best able to coordinate the range of clinical and psychosocial services available locally and direct clients to those services.

They already develop strategic regional mental health plans (of varying quality).

We acknowledge that few PHNs could now fulfil this new triage and monitoring role.

PHNs receive only a small fraction (< 10%) of the total federal government expenditure on mental health.

They will need additional support, particularly to implement the digital infrastructure to enable individual tracking, planning and reporting.

However, this role is critical if we are to help people find the right care quicker, not get lost, not lose hope.

A key role for the defunct Partners in Recovery Program was this kind of coordination.

Changing the experience of care

The second critical function for this ecosystem to work well and fundamentally shift the experience of care for people is a new and central role for specialist assessment, review and support to be provided by psychiatry, clinical psychology, or mental health nurses.

Repeated inquiries have determined that people still regularly struggle to have the true nature of their mental health needs understood and dealt with, leading to misdirection, disillusionment and misadventure.

This kind of specialist advice is offered in many states and territories for a very limited number of potential service users and often with a limited scope of presenting problems.

Such systems use publicly employed (and often hospital-based) specialists to assist GPs and other primary care providers with care for more acutely unwell or complex clients in the community.

However, this kind of tertiary support is often only made available for a few hours each week.

There are some examples of more elaborate or generous approaches to this kind of consultant psychiatry service, such as the Primary Care Psychiatry Liaison Service (PC-PLS) trialled at the Western Sydney PHN, drawing on concepts such as the Wellness Support Teams developed in New Zealand.

Discussions with colleagues in New Zealand indicate the effectiveness of this work in bolstering the effectiveness of primary mental health care better managing people with complex mental health problems in the community and forestalling hospital readmission.

This kind of specialist advice must now be made available not only to professionals but also directly to potential service users.

Getting the best advice as soon as possible about what to do given your mental health needs is vital and could be a key role for the new head to health hubs being established across Australia.

A national system of psychosocial support services

A third key piece of infrastructure is a national system of psychosocial support services, to operate as partners with clinical service providers.

These services, often provided by non-government organisations (NGOs), have been a peripheral element of the Australian mental health service landscape, receiving just 6% of total state and territory expenditure.

By contrast, in New Zealand, these services account for one-third of all funded mental health services, offering multiple service opportunities in the community mental health sector (including peer-run acute care) unavailable here.

The Mental Health Professional Network that was put in place to facilitate implementation of the Better Access Program should be replicated to familiarise primary care practitioners with psychosocial services, local providers, and social prescribing options available to them.

Getting the right care at the right time

All the elements described thus far are designed to enable the effective staging of the mental health service response, across both psychosocial and clinical services, so that the person gets the right level of help at the right time.

The need for better, quicker triage and assessment in mental health has already been acknowledged by the federal government, which has invested in development of a new tool (the Initial Assessment and Referral Decision Support Tool [IAR-DST]).

However, there is doubt about whether this tool can adequately differentiate the various clinical and psychosocial needs of individuals presenting to services.

For example, the IAR-DST provides little differentiation between the need for specific clinical care that requires mental health interventions delivered by mental health professionals (eg, psychologists and psychiatrists), from the need for allied medical services for comorbidities (eg, physical health, substance misuse) delivered by GPs, nurses, and drug and alcohol workers, or from other psychosocial needs requiring more social, welfare, employment, and/or housing support.

So, although the goal of more accurate assessment and treatment is acknowledged, Australia’s current mental health system lacks the scalable infrastructure to assess a person’s current and ongoing needs consistently or accurately. This is a recipe for ongoing waste and ineffectiveness.

Patient-reported outcomes measures

To increase the power of the IAR-DST, patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) can be used to assess a person’s needs across multiple dimensions.

They can generate more consistent ratings, more resistant to potential biases across settings.

Outcomes and needs can be tracked within the same digital infrastructure to provide a dynamic assessment of a person’s needs over time (as opposed to static, one-off assessments at point of entry or review).

The need for change

The system requires some major changes to the way people could access more specialised psychological care. It proposes removing one barrier, namely referral via a GP. It recognises that access to GPs is restricted by availability, out-of-pocket costs, and distribution of practices.

Further, it also recognises that many people would prefer to access psychological care directly and independently of their other primary health care or psychosocial needs.

Consistent with our dynamic system modelling of what would deliver optimal outcomes for service users, it maintains an essential triage function that would assist people to access the right care, first time, where they live.

It does not propose a government-funded open access to psychological or psychosocial care.

This new ecosystem seeks to augment generalist care, using those clinicians to deliver specific types of clinical care (eg, integrated medical and psychological care, prescribing of and ongoing monitoring of appropriate psychotropic medications) alone or in team-based care with other professionals or linked to other psychosocial services (including the concept of “social prescribing”). Within this model, patients who present through their own GP would still be able to enter the new ecosystem directly or via the PHN-coordinated network.

The goals must be for people enter at low (or no) personal cost, express their own specific clinical and psychosocial needs, find the right clinical or psychosocial service the first time they present, and carry relevant prior and current treatment information across relevant clinical and psychosocial service providers.

The impact of the services they receive must be assessed and monitored, with dynamic coordination so that the system responds to a person’s changing needs.

One of the distinguishing features of our current approach is the lack of systemic accountability. The tools described here offer greater connection and coordination, permitting enhanced systemic oversight to, for example, explore whether primary mental health care prevents unnecessary hospitalisation. This is currently not reported.

It should be the aim for our primary mental health system that every time someone seeks help for care, their needs are appropriately assessed and responded to in a personalised but standardised way and with equity and consistency. This is not beyond us.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg is a Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre at the University of Sydney.

Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director, Health and Policy at the Brain and Mind Centre at the University of Sydney. He holds a 3.2% shareholding in Innowell Pty Ltd, which delivers digital mental health tools.

Dr Frank Iorfino is an early career researcher for the Brain and Mind Centre at the University of Sydney.

You can read more about the authors’ work here.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Hello All,

RE: ‘We need to respect expert GP care coordination. Focus on the therapeutic alliance that’s already there and stop viewing patients as widgets. We need investment in the trained workforce that’s already here so we can attract more and retain those GPs ED consultants, nurses, social workers police, psychologists and psychiatrists who are leaving.’

Couldn’t agree more. From experience working with young people in a tertiary care centre for anorexia nervosa, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals rely absolutely on the bedrock of GP care coordination. GPs have the essential alliance and trust of families and young people, along with in-depth knowledge of their medical and mental health needs and can most efficiently plan their care.

Computers and questionnaires are definitely useful. Like any tests, however, questionnaires have well recognised limitations, and are best used to inform clinical decision making, in the same way that we use any test. If a test result doesn’t seem right, we repeat it to make sure.

Post-pandemic with workforce shortages, there is a need for respectful dialogue, and united action on better funding primary mental healthcare, as the foundation of the whole system.

Noting all the cogent anonymous replies should be enough of a red flag as to what is going on here.

Nonsense reinvention of primary care. It’s already here and we don’t need a new world order. What we need are thought leaders that integrate and respect the dynamism of expert generalists. PHNs are yet to prove ROI.

We need to respect expert GP care coordination. Focus on the therapeutic alliance that’s already there and stop viewing patients as widgets. We need investment in the trained workforce that’s already here so we can attract more and retain those GPs ED consultants, nurses, social workers police, psychologists and psychiatrists who are leaving.

Fix the workforce resources problem with investment.

Stop the advertorials for fragmentation.

Stop fragmenting patients into disease specific boxes but wrap around the care with expert generalists.

Focus the political on the social determinants of health care in public health. Employment, Housing, Education, Income security, Food security, Early childhood, Social inclusion, Conflict free environments, workplace safety, AND accessible affordable healthcare.

This is entirely the wrong lens on system reform.

Do the authors actually understand what GPs do? Do they think we are sitting in our clinics worrying about Medicare rebates and counting our pennies rather than actually seeing and caring for patients? That we don’t know just about every little nook and cranny of local service provision where our patients can access help? That we don’t understand what our patients need and how to refer to appropriate services?

Disappointing to see these ivory tower psychiatrists with no concept of what highly skilled GPs actually do still pontificating on so-called solutions that would only make things worse for many and disastrous for some. GPs are highly trained whole person carers who are locally placed with existing networks. We need colleagues and systems to support our care not sideline us- we are well placed to help our patients access the care they need if we cant provide it ourselves. We’d like our Psychiatry colleagues to focus on getting their own shop in order – more accessible affordable and collaborative tertiary care please!

Please MJA make space for new voices who seek to collaborate and respect each others’ expertise?

By all means let’s improve the ecosystem, increase the entry points, collect better data and enhance accountability. But don’t replace the warm relational care of trusted professionals by cold bureaucratic triage and tracking systems – this will increase inequity by ignoring digital disadvantage. Let’s also focus on social determinants of mental ill health and on empowering individuals and communities to seek out strength based solutions rather than pathologising labels.

Perhaps starting by getting the existing system to work as intended would be a more logical starting point. Let’s properly address contributors to childhood trauma – fund parenting supports and address poverty for the highest risk groups. Let’s get tertiary services to act like consultants – review, diagnose and RETURN patients with to primary care for their ongoing care. Let’s get those with challenging needs seen and supported by the tertiary system – access to that system should be determined by disability NOT diagnosis. Let’s address issues like basic the income and housing needs of our community. Let’s fund primary care to spend time with complex patients – and stop funding high throughput GP which serves no one (especially not the budget) well. The problems in mental health will not be improved by costly systems of triage such as the IAR and online CBT.

Do the authors live in the real world or just an academic one? The IAR-DST is a complete waste of time and money. It has not changed my recommendations for patients in any way. In the PHN funded training for the IAR-DST the answers for the same patients varied between clinicians making it entirely unreliable The money spent on this could have been better invested in public funding for real-life multidisciplinarian treatment services. Good psychiatrists have disappeared into the rabbit hole of financially lucrative telehealth and outrageously expensive specific “ assessments”. Yet they continue to throw rocks at the GPs who do the majority of mental health care for those who can’t afford the large gaps.

The authors state that “The goals must be for people enter at low (or no) personal cost, express their own specific clinical and psychosocial needs, find the right clinical or psychosocial service the first time they present, and carry relevant prior and current treatment information across relevant clinical and psychosocial service providers.”

The entry point already exists – it is general practice, emergency departments and community health.

How does the team see the provision of psychological services, psychiatric services and social services being readily available for these services to interface with ? Will more psychologists and psychiatrists take up salaried jobs and work out-of-office-hours?

It recognises that access to GPs is restricted by availability, out-of-pocket costs

Why not fix the core problem ?

GP service responses are often reduced to just four specific mental health interventions:

• Prescribing medication

• Referring to a psychiatrist for another medical opinion

• Referring to another non-medical professional (overwhelmingly a psychologist) for a specific psychological intervention

• Conducting psychological treatments themselves. Based on the Medicare numbers reported, this option remains very rare. Of the 2.9m GP Medicare services reported (see Table 1 above), only 25,000 were for delivery of ‘focussed psychological strategies’.

This characterisation of what we do is, of course, demonstrably wrong. We no longer have BEACH, but if the Brain and Mind ever consulted GPs rather than just explaining to us what we do (nothing about us without us maybe?) they may finally accept that the way we bill is not a surrogate for what we do.

That would not be expedient for Brain and Mind who, lets face it, and heavily subsidised to create digital “solutions”. We are tired to the bones of this sort of nonsense making its way into policy. And who does it benefit? Good question. Considering I earn a sixth of the income per minute doing MH, I would hardly fight to do more unless I had the patients’ interests at heart. I have plenty of other patients needing simpler care after all.

Patients need more access to GPs, mental health nurses, social workers & psychologists working within local GP clinics to improve access and outcomes for patients and provide integrated wrap around care.

Disadvantaged patients can’t afford internet devices or data to access online services. They need face to face interactions with clinicians in their community without the long waits or high gap fees.

Dear MJA, when publishing articles about GP deliver of mental health, please consider articles with GP authors as part of the team. As GPs, we deliver the a large proportion of care in this space- in our area our access to psychiatrists is near zero and all the psychologists are charging $250/ session which almost none of our patients can afford . It is impossible for someone to be admitted unless scheduled which means we might review our semi psychotic or suicidal patients daily at times .Tthere are already established referral pathways -HealthPathways and local education networks, including links to social prescribing that GPs have themselves developed. Some people do self refer to counselling and even psychology via private health insurance/ defence/victims compensation but they all still need to see their GP for other care.

As a GP, tools like the IAR-DST take more time if talking to people and GPs are not funded to di the assessment- I entered details of some recent patients through this and every time it came up with send to ED(ED refuse to see) , see a psychiatrist or psychologist (not possible due to cost) or see a GP (patient already with us) we welcome better access to counselling / psychology but maybe lack of these is because of controlled access to training. Better funded and respected primary care is also part of the picture.

“The natural enemy of theory is data” – Goethe. Have there been demonstrable improvements in care outcomes from these initiatives?

Right, so exclude GP’s who are the ones seeing the most complex and largest volume of mental health patients and hand over to PHN’s who won’t collaborate with GP’s. How is this not fragmenting care!

This model is in no way patient centred or trauma informed looking at the issue as if it is a linear recovery model. It is not realistic in any reality of real patients with mental health conditions.

“GPs are concerned about survival, Medicare rebates, and asserting a role as expert generalists. Psychologists focus on session limits, responding to needs of people for whom the Program was never intended.” Any comment on what psychiatrists with empires built on digital entrepreneurship are interested in?

You’ve stated “Consistent with our dynamic system modelling of what would deliver optimal outcomes for service users, it maintains an essential triage function that would assist people to access the right care, first time, where they live.” I assume “it” is the highly cited innowell platform, or its equivalent.

Is this the dynamic systems modelling that estimates the recovery rate using online services using a 2004 paper? Before we had google and we all were using myspace? Or the trials of Innowell, one of which was never published, one used 16 people with no mental illness “who finished some of the survey” and one states that follow up of young people with acute suicidal thinking “within an average of 7 days” is evidence or “accessible, timely care”. Oh, and is this also the “dynamic systems model” where over 70% of the effect sizes are “estimated using constrained optimisation” which should produce a range of possibilities, where the paper presents a nice, accurate looking line. Which just happens to suggest that technology is a good idea.

No thanks. Just because it has numbers, doesn’t make it evidence. Just because it creates graphs, doesn’t make it defensible. But being scientists, and economists, you would know that right? Implying GPs and psychologists are conflicted by their own interests while Brain and Mind is a pure scientific enterprise with objective truths is, frankly, a little bit rich.

Suggestions to hand over more responsibility to PHNs highlights the clear lack of experience of the authors in working with PHNs. In fact, why do we have those with expertise in secondary and tertiary mental health proclaiming expertise in the primary care space anyway.

Outcomes and needs can be tracked within the same digital infrastructure to provide a dynamic assessment of a person’s needs over time (as opposed to static, one-off assessments at point of entry or review).

No link here. Is this component based on Innowell / Project Synergy?