An important takeaway from the survey was its insights into GPs’ own health monitoring behaviour.

HYPERTENSION is the single largest contributor to cardiovascular mortality and morbidity worldwide. Challenges abound in appropriately diagnosing and managing hypertensive patients, with difficulties in achieving guideline-recommended goal blood pressure (BP), treatment resistance, management of drug side effects, and patient adherence being particularly notable.

GPs have formed the front line of hypertension management in Australia and have borne the brunt of these challenges. Against this backdrop, the recently published GP Qualitative Market Research report 2022 (data on file) provides several sobering insights into GPs’ cardiovascular risks and the state of hypertension management in Australia.

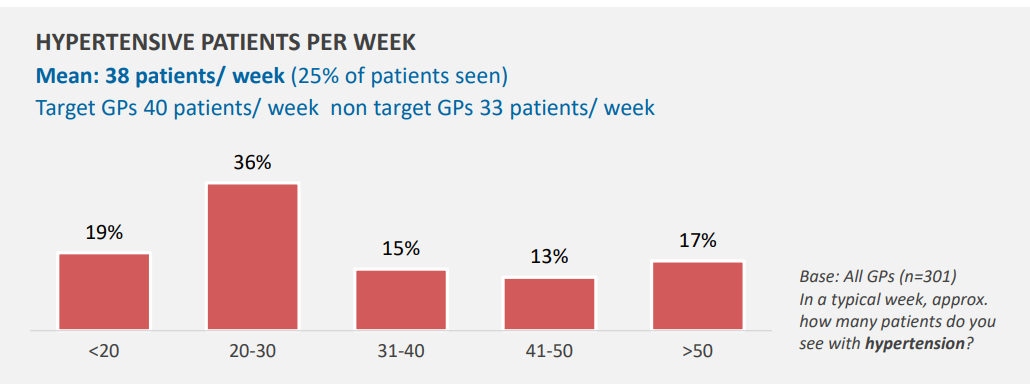

This quantitative survey, conducted online in May 2022, received responses from 301 GPs, typically working in group medical centres nationwide. The respondents consulted an average of 38 patients with hypertension per week, representing a quarter of all patients seen (Figure 1).

Figure 1

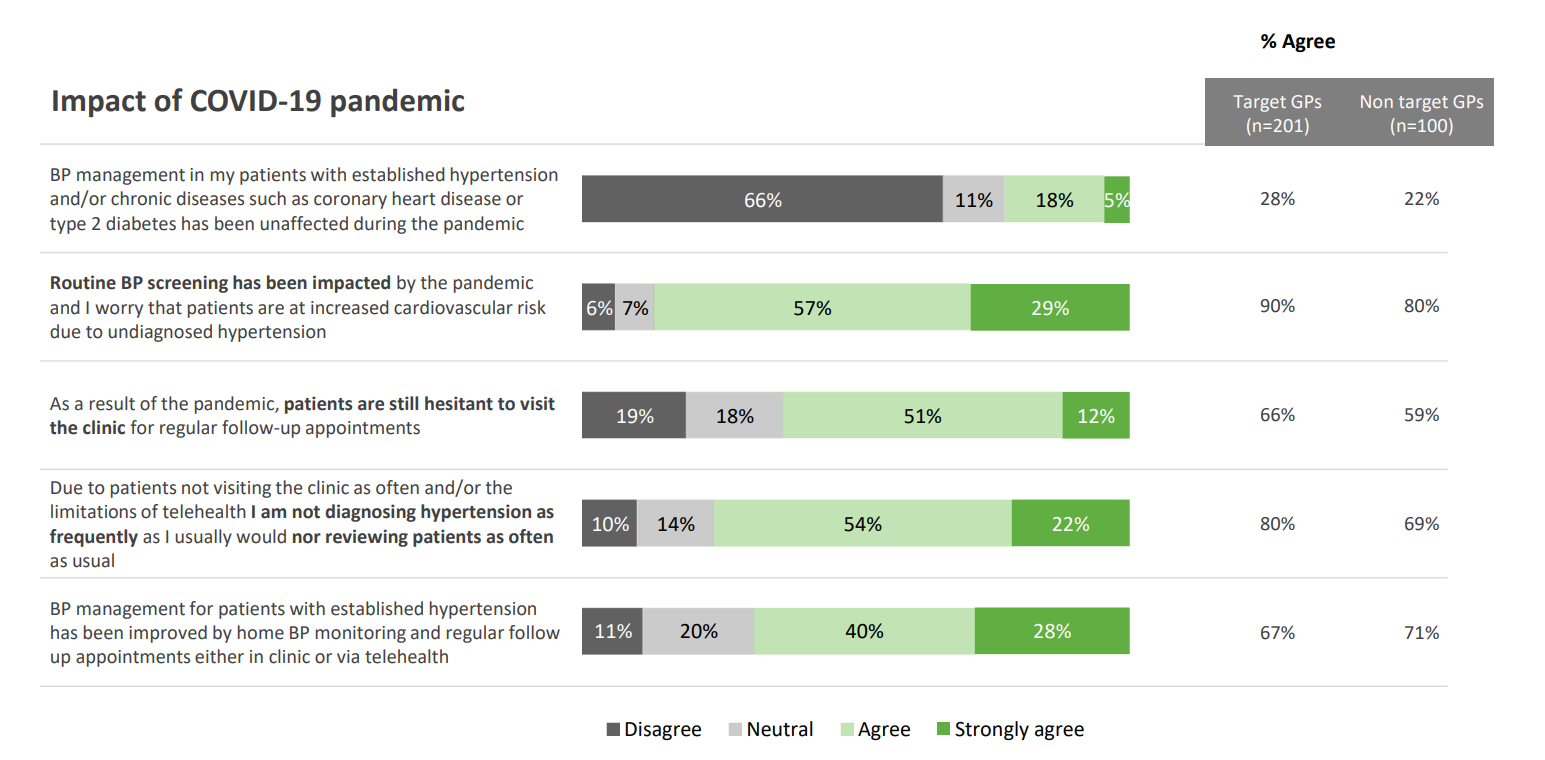

Not surprisingly, the dramatic impact of COVID-19 and associated public health control measures was writ large, with a majority (86% of survey respondents) agreeing that the pandemic had greatly affected routine blood pressure (BP) screening.

Despite the lifting of most non-pharmaceutical public health interventions in mid-2022, two-thirds of survey respondents indicated their patients still remained hesitant to visit their clinic for routine, in-person follow-up appointments. Even though home blood pressure monitoring could reasonably substitute for in-clinic monitoring, the initial diagnosis of hypertension still hinges on blood pressures measured in clinic over serial visits. Such hesitancy could have an adverse impact on the timely diagnosis and optimal management of all chronic diseases, including hypertension, with implications for future rates of cardio- and cerebrovascular events (Figure 2).

Figure 2

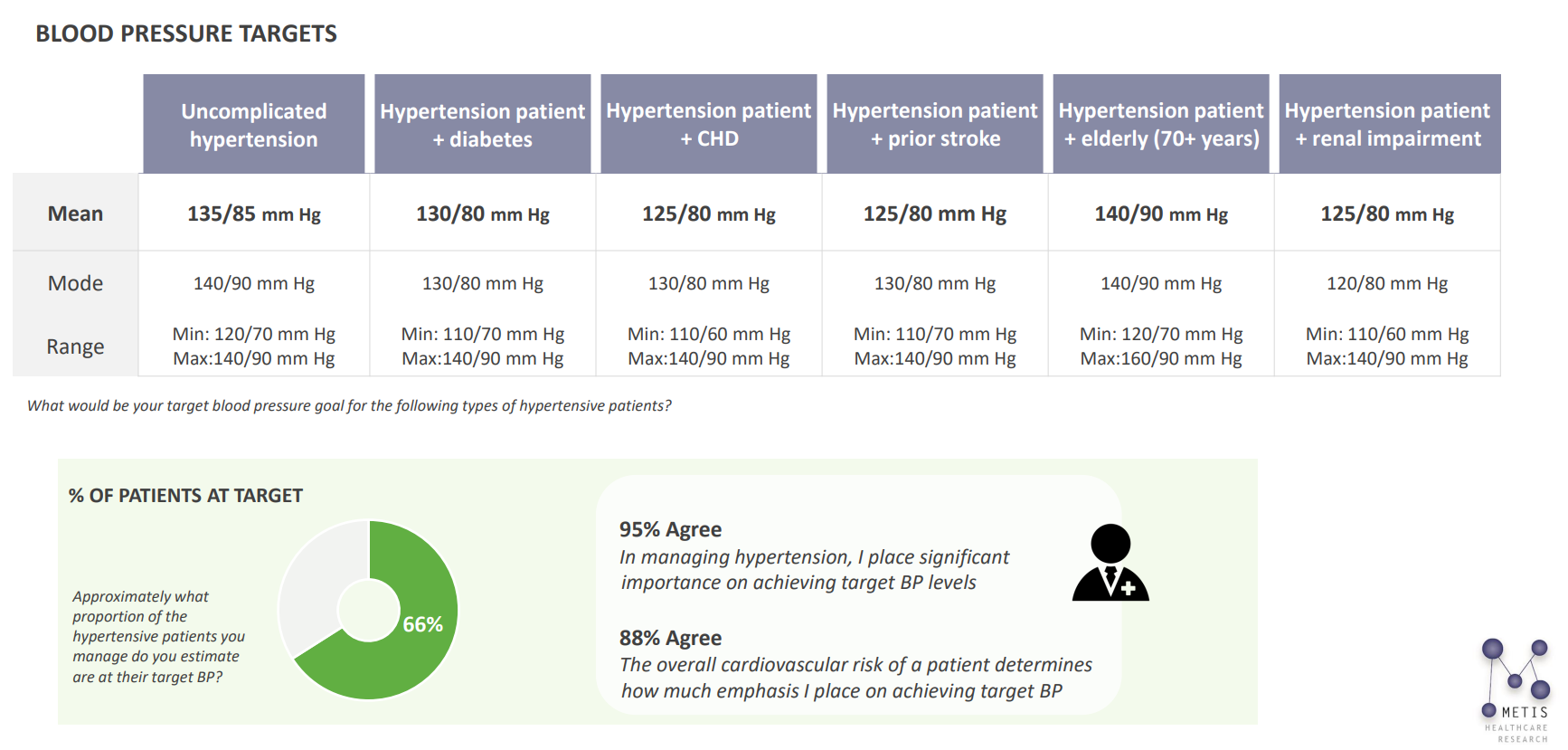

Notably, survey respondents reported that 66% of their hypertensive patients were controlled to target BP (Figure 3) – a surprisingly high proportion compared with BP control rates described in a recent “Call to Action”, which highlighted our lagging status in rates of hypertension control compared with the US and Canada. Only 32% of hypertensive patients are controlled to target thresholds in Australia – substantially less than the US (44 %) and Canada (65%).

Figure 3

Although it is plausible that the respondents to this survey managed to achieve a high degree of control among their patients, one cannot avoid speculating that several had perhaps made an overly optimistic appraisal. Under-reporting of elevated home BPs by patients is well described.

Additionally, clinicians may dismiss elevated clinic blood pressures as being confounded by a white coat effect, without first carefully confirming this effect with a 24-hour ambulatory BP monitor (ABPM), or with systematic home blood pressure monitoring. The concept of “control” indeed may be elusive when patients frequently fluctuate between normal and high blood pressures in the space of minutes to hours. Given these considerations, erroneously misclassifying patients as being well controlled when the converse is true, is an easy trap to fall into. The inaccurate estimation of BP control carries significant implications for those patients whose blood pressure is less well controlled than assumed, with undertreatment potentially leading to a plethora of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

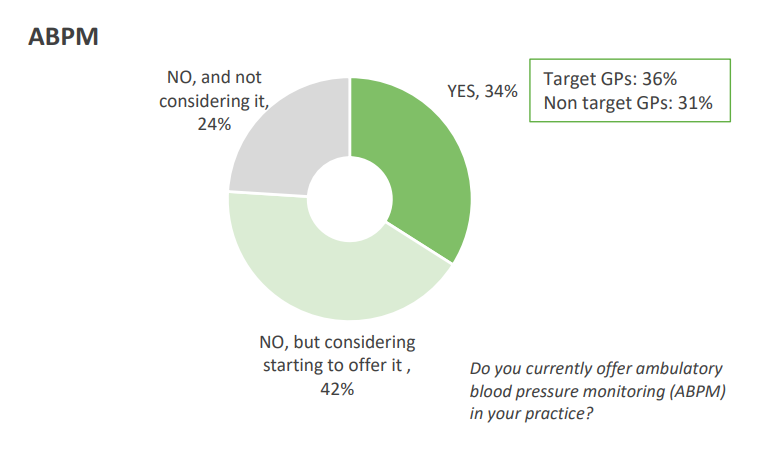

ABPM is widely considered the gold standard test in defining hypertension control, excluding white coat hypertension and identifying masked hypertension. Given this, it is encouraging to note from the survey that up to a third of the GP practices that responded to the survey now offer this test, with more interested in offering it in the future (Figure 4).

Figure 4

ABPM has only recently received a Medicare rebate for the diagnosis of hypertension in treatment-naïve patients and interpretation of its results are largely left up to the GP, with often little formal training or experience. Therefore, such training is of paramount importance.

The Medicare rebate currently excludes patients with an existing diagnosis of hypertension, or those who are already on antihypertensive therapy. Clarifying if adequate control has been achieved in this population is arguably as important as excluding white coat hypertension in a generally low risk population. Indeed, guidelines for the investigation and management of resistant hypertension recommend ABPM to exclude pseudo-resistant hypertension. Although the rebate for ABPM in treatment-naïve patients is an important first step, expanding the indication to treated, high risk patients to precisely identify those with suboptimal control will be key.

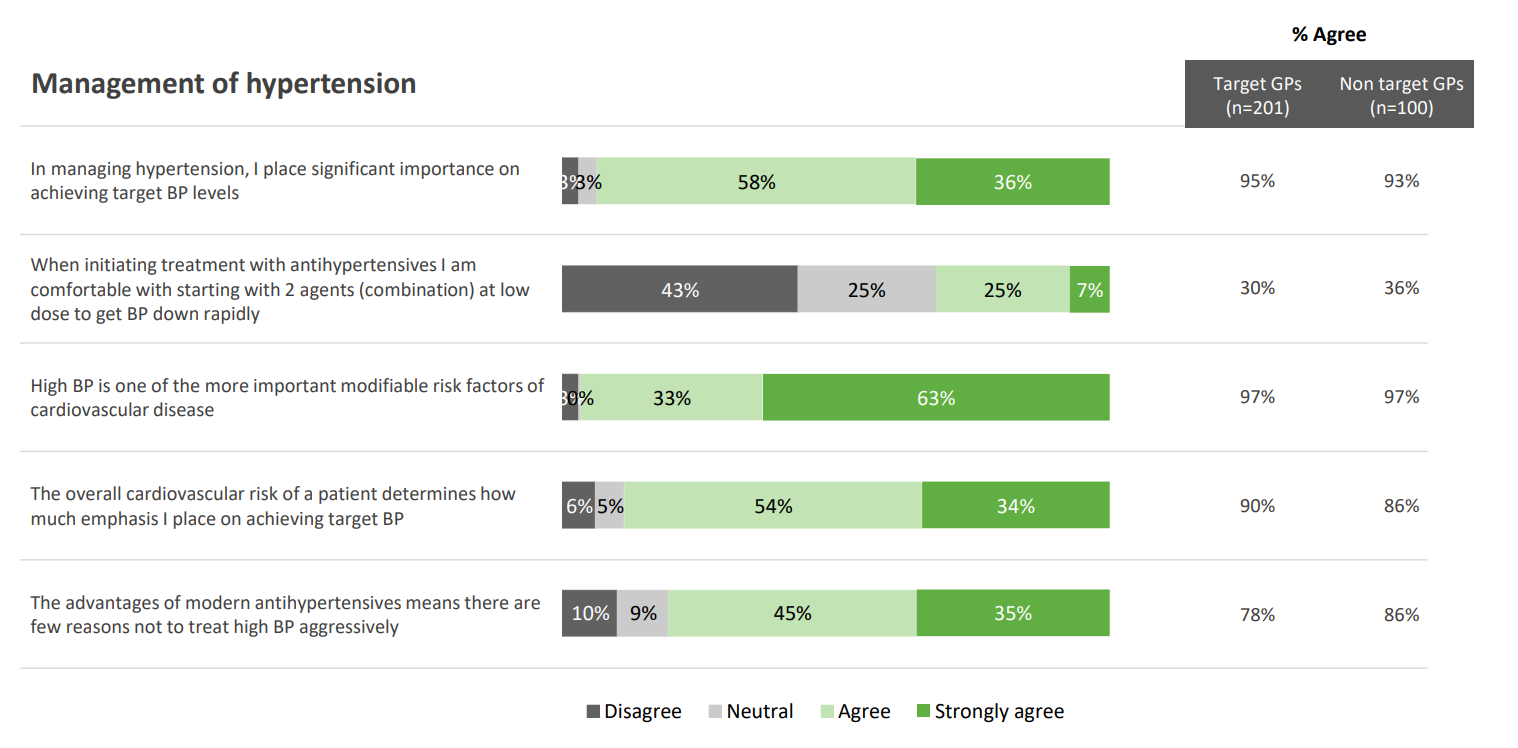

Regarding management, eight out of ten of the surveyed GPs agreed that the advantages of modern antihypertensives meant there are few reasons not to treat high BP aggressively. Interestingly, a third of GPs surveyed were comfortable with starting low dose combination therapy, despite current Australian guidelines still recommending initial monotherapy (Figure 5). The use of up-front combination therapy has been a key recommendation of the European guidelines since 2018 and the International Society of Hypertension and World Health Organization guidelines more recently.

Figure 5

The use of low to moderate dose combination therapy of generally complementary agents (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs] plus calcium channel blockers [CCB] or angiotensin receptor blockers plus CCB) is widely recommended in international guidelines, not only because such a strategy results in higher rates of BP control but also as the risk of side effects is reduced.

Trials such as SPRINT have also changed the landscape with respect to goal BP. Hence both the European and American guidelines recommend a BP target in most patients of less than 130/80.

These survey findings indicate the glaring need for a comprehensive update to our Australian guidelines, together with a concurrent updating of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme prescribing restrictions.

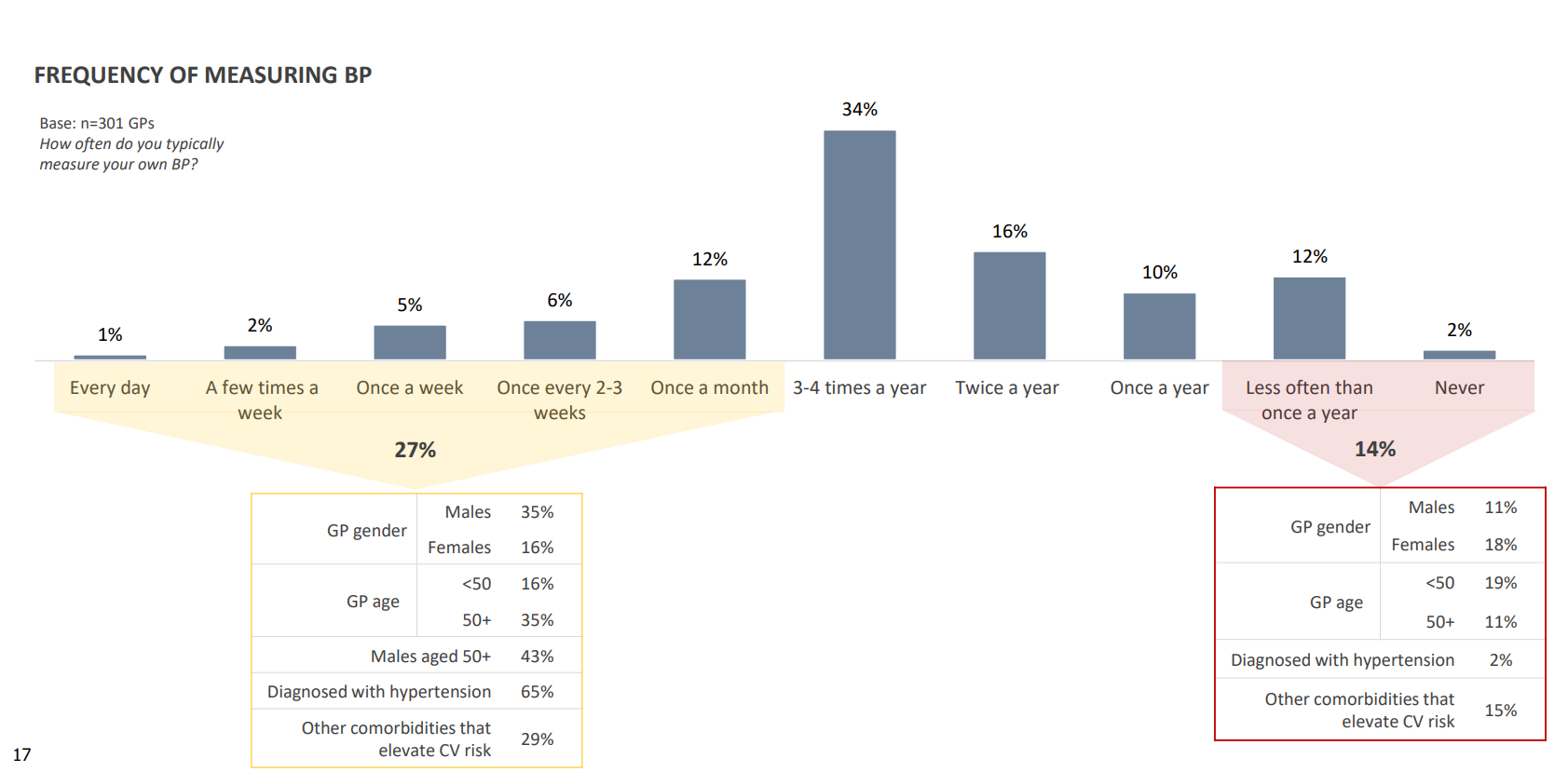

A final, important takeaway from the survey was its insights into GPs’ own health monitoring behaviour.

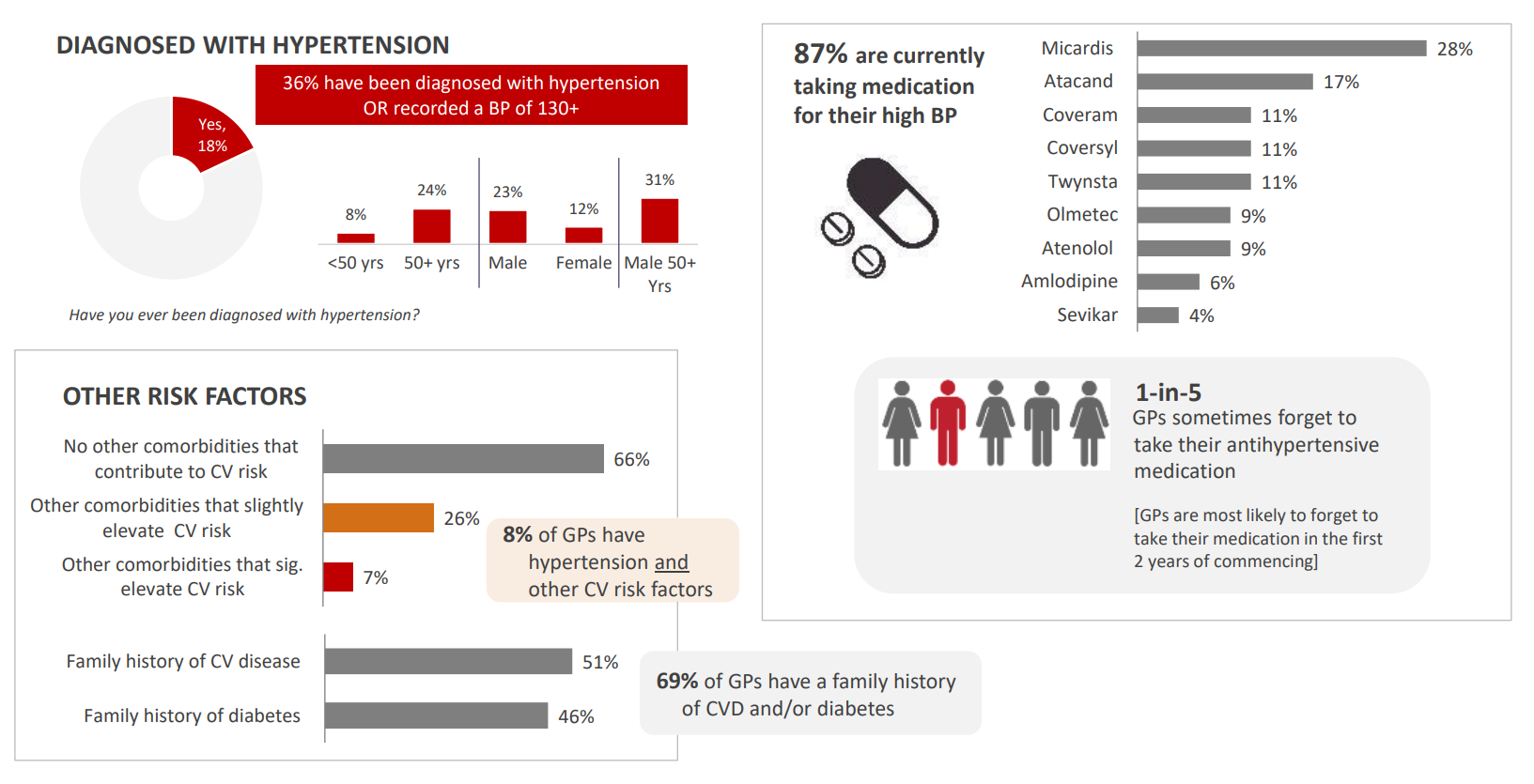

One in seven respondents reported not having checked their own BP at least once a year (Figure 6). Before this survey, a third of the responding GPs had previously been diagnosed with hypertension or had recorded a systolic BP in excess of 130/85. Eighty-seven per cent of these GPs were taking antihypertensive therapy, with the majority receiving ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (and not combination therapy) (Figure 7).

Figure 6

Figure 7

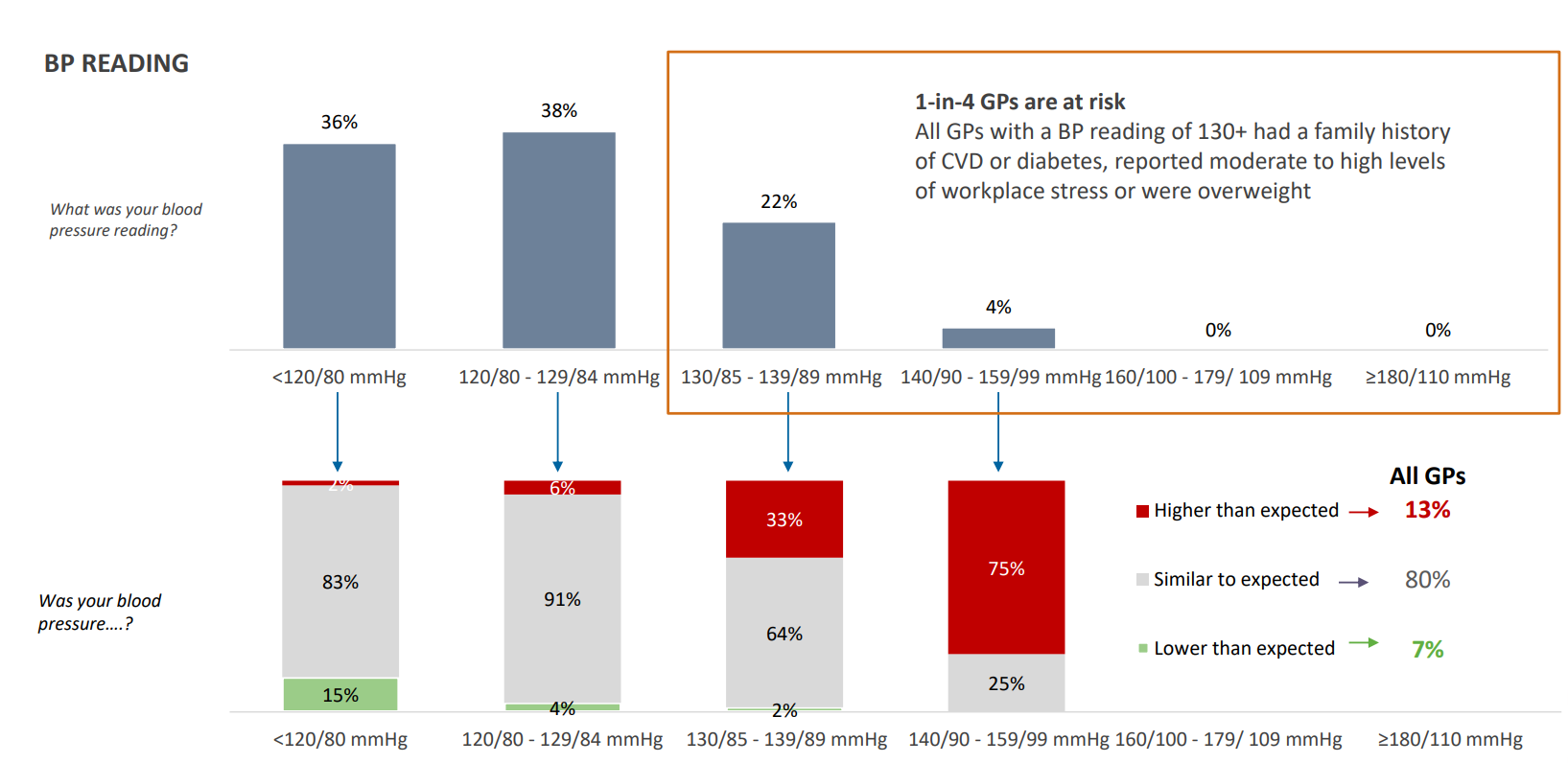

Upon measuring their own BP as part of the survey, one in four respondents measured a BP greater than 130/85, with all such GPs having a family history of cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes, reporting moderate to high levels of workplace stress, or being overweight. Even more concerningly, 75% of respondents who measured their BPs at between 140/90 and 159/99 stated that these readings were substantially higher than expected (Figure 8).

Figure 8

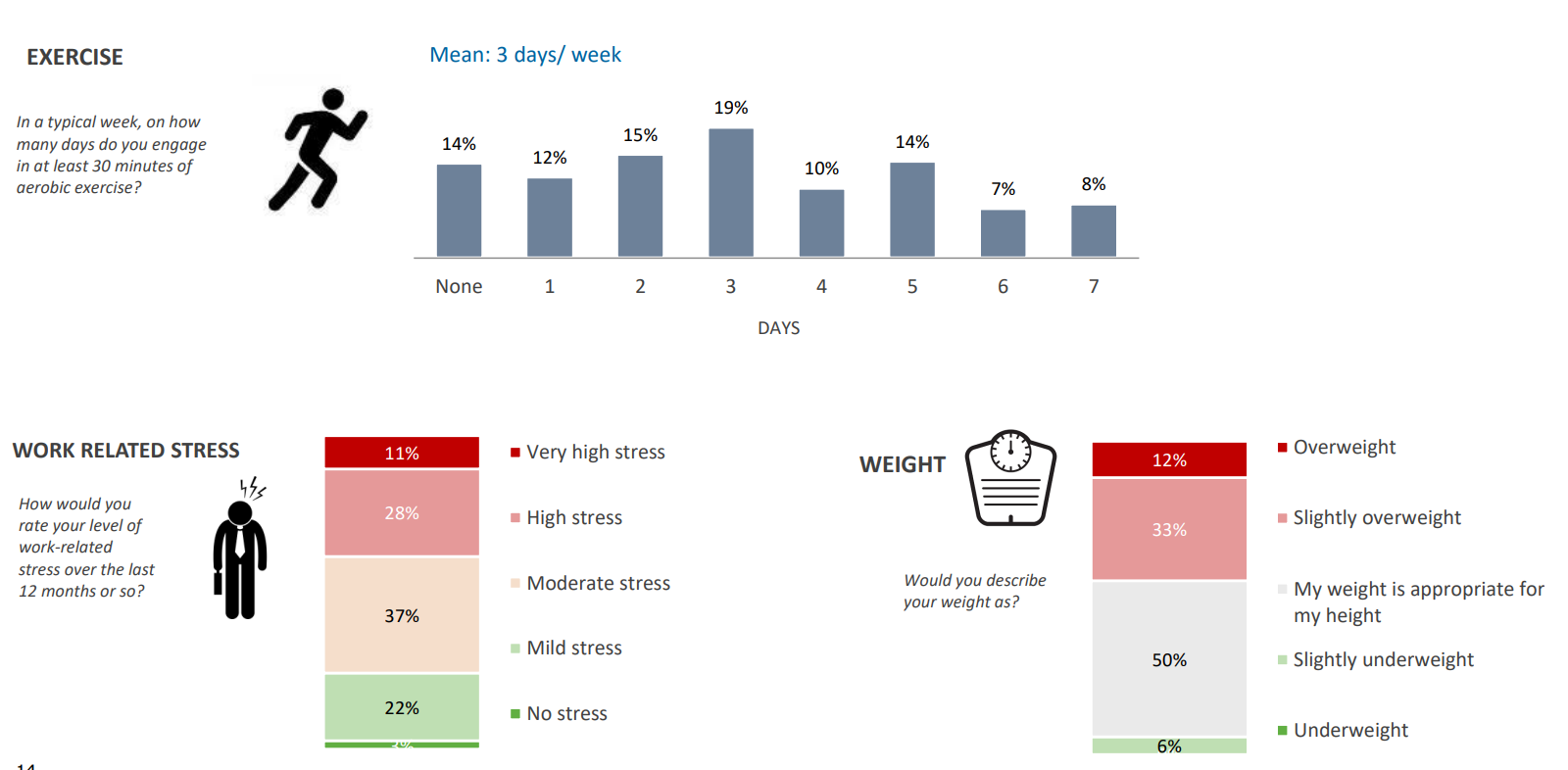

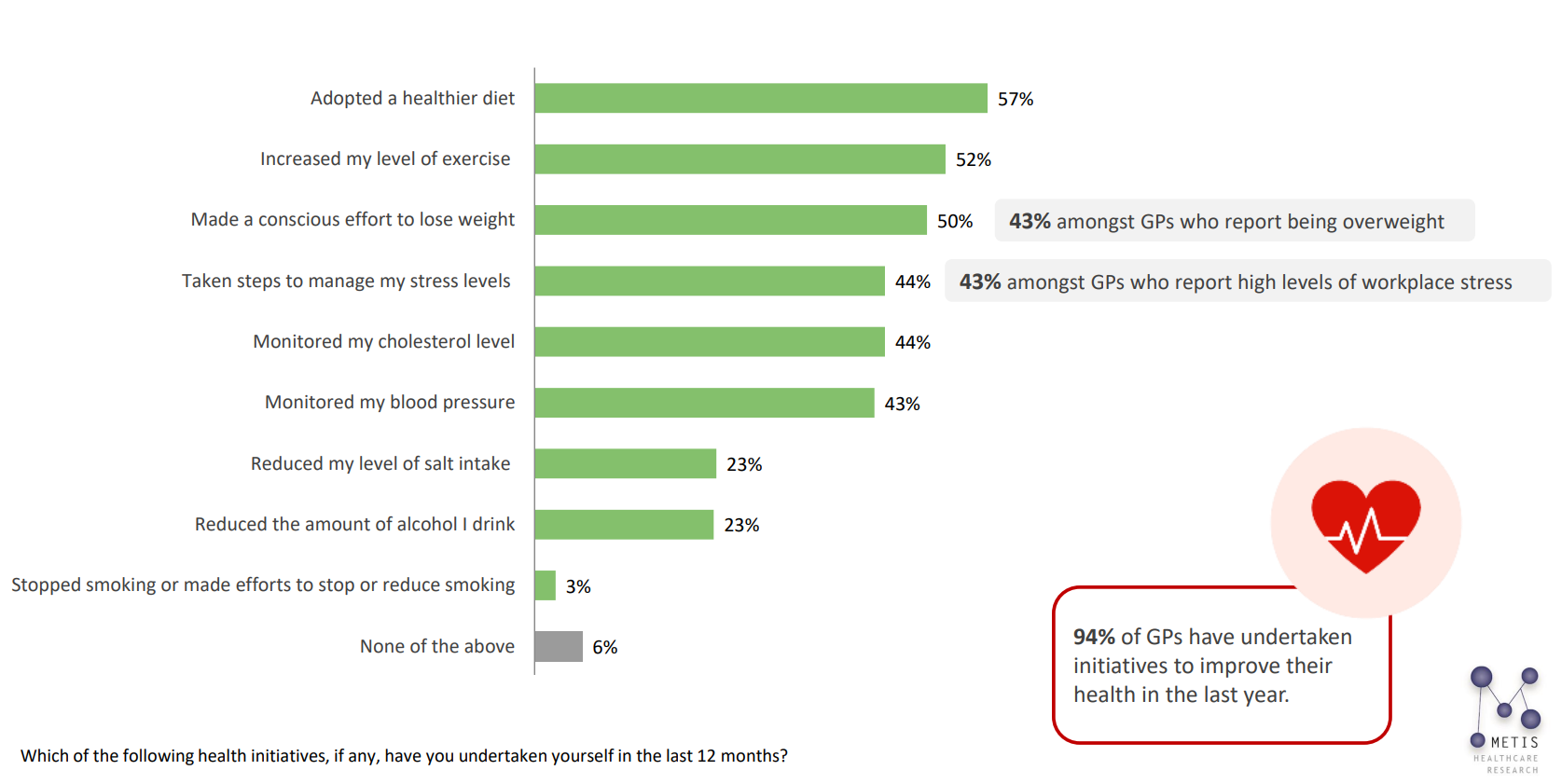

These findings emphasise the challenges that medical practitioners face in seeking and obtaining routine medical care for themselves. Three-quarters of respondents reported moderate to high levels of workplace stress, and nearly half described themselves as being overweight (Figure 9). Less than half the GPs who reported being overweight attempted to lose weight, and less than half of GPs who reported high levels of workplace stress were able to address their stress levels (Figure 10).

Figure 9

Figure 10

These findings are an indicator of the pressures faced by our frontline doctors, who are perhaps placing their own health and wellbeing secondary to that of their patients. GPs and other medical practitioners should be supported to “put their seat belts on first”.

A recent article published in the MJA by Wijeratne and colleagues highlights the prevalence of psychological distress across the medical profession. One could argue that a national health strategy promoting the cardiovascular health of medical professionals would be just as important.

Despite being subject to the usual caveats that come attached to surveys, these findings provide a unique snapshot of contemporary hypertension management from an Australian GP perspective. It comes as no surprise that COVID-19 is continuing to cause immense disruption to the management of hypertension and chronic health conditions generally.

An urgent, profession-wide effort to re-engage with patients who have either become disillusioned or disengaged with routine health care is critical if we are to avoid a future reckoning in cardiovascular events.

In addition, clear and updated guidance on hypertension management is needed to resolve multiple discrepancies in the use of combination therapy, to define the role of ambulatory BP monitoring, and to clarify BP goals in treated patients.

Finally, the findings in relation to the GPs’ own health behaviour are particularly unexpected, and troubling, and while several practical solutions could be suggested, a more holistic college- and/or profession-wide response is urgently required.

Dr Om Narayan is an interventional cardiologist with a particular interest in hypertension at the Northern Hospital, Melbourne. He established the first comprehensive hypertension clinic, caring for patients with resistant hypertension at MonashHeart (Monash Health), Melbourne, and is passionate about enhancing clinical outcomes for patients living with hypertension.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

We must continue to press for ABPM for patients with known HTN

Home monitoring done well, is very very useful, but obviously doesn’t capture onight BP and also necessary for patients unable/unwilling to do home monitoring

GIGO. We all have some understanding of how reliable such survey data is. At best, such data allows to detect a trend, at worst it has no correlation with reality. It all depends on the sampling and the inherent biases in the surveyed people and issues.

Here, 301 GPs were surveyed in a “market research” & the responses used to produce this paper. Is that representative for all GPs? Were the responses truthful and accurate?

Deriving specific percentages that should inform significant policies from such survey data is a capital crime in statistics / research. Such data, at best, is good enough to justify a proper investigation accessing real data (which costs a lot more resources than a simple survey)