Knowing the extent of self-harm and suicide ideation in our communities, particularly in our young people, necessitates immediate investigation and action.

THE “Iceberg effect” is an expression used by researchers and policymakers to describe the incidence of self-harm and suicide attempts in samples of people from western countries.

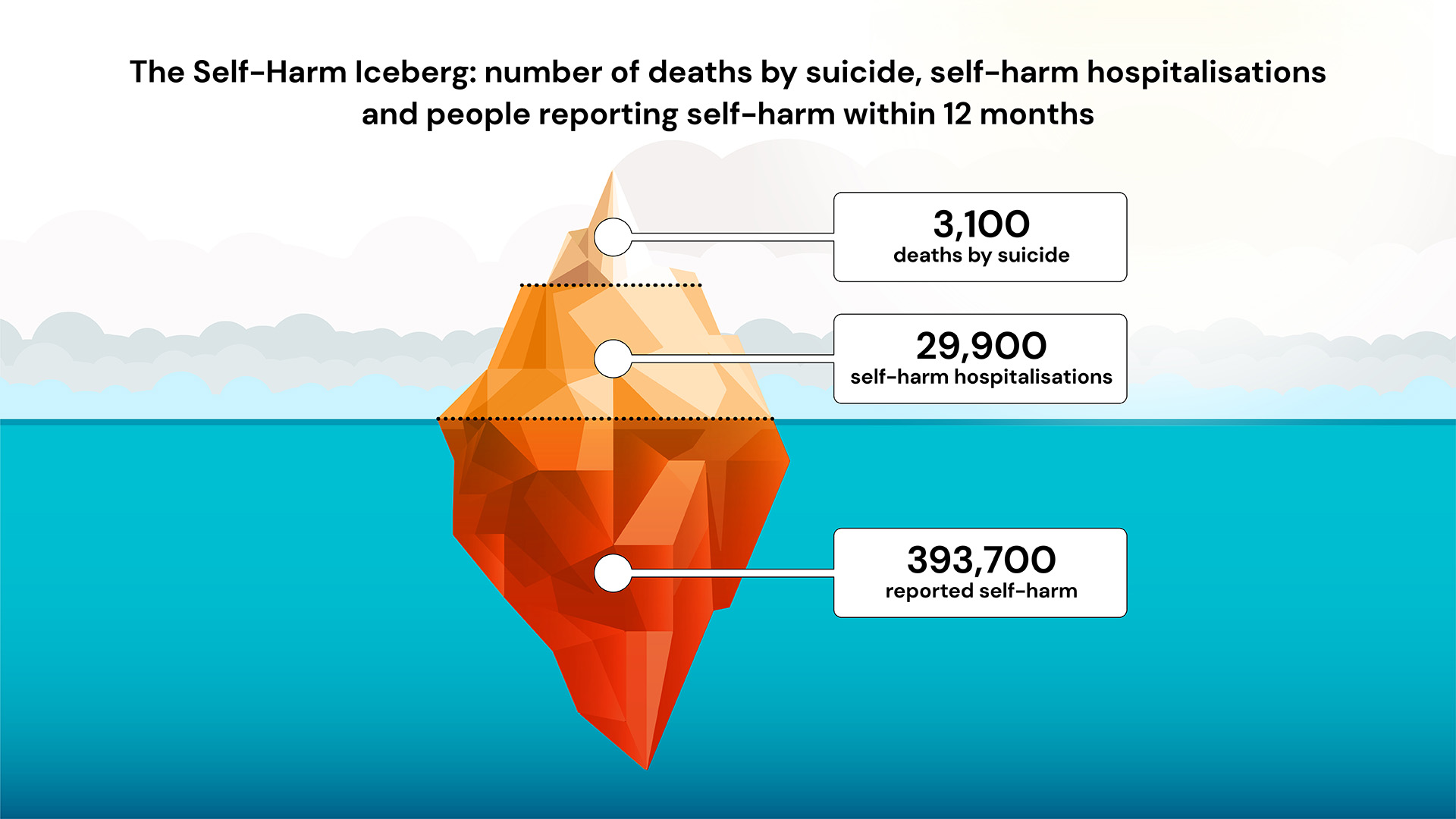

At the very top, emerging from the sea, are the people who die from suicide; in the middle are those who are in contact with health services and so identified “at risk”; and at the bottom and underwater are the majority who have thoughts of or attempts at self-harming but remain submerged to the light of day.

Establishing the extent of any problem is the first fundamental stage in addressing it.

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (released July 2022) is to be praised for its first-time work in estimating the prevalence of self-harm in our community. The ABS defines self-harm as referring to “a person intentionally causing pain or damage to their own body”. Self-harm can but may not necessarily involve suicidal intent, and can be used as a way to cope with or express emotional distress.

The ABS methodology used surveys of Australia’s population from 16 to 85 years of age to give us a better insight into the subterranean bottom that had not been captured in previous population-level data. Before the survey, we knew that emergency hospitalisations for self-harm were rising for young people. But now, by asking the public about their experiences, we know how many people have self-harmed without reaching hospital. These new data can be combined with even more recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) on suicide deaths (the tip) and self-harm hospital admissions (the middle).

How does the iceberg look?

Let’s start with the tip.

Every year, about 3100 people die by suicide, many of these young or adult men, reflecting a slight upward trend since around 2011. The latest national data indicate 3139 deaths during 2020. Just over half of these deaths occurred in mid-life, in people aged 30–59.

However, despite the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been no recorded increase (as yet) in the number of deaths over 2019–2022. The latest data from New South Wales (one of the most comprehensive record-keeping states) reveal non-significant differences. From 1 January 2022 to 31 July 2022, there were 586 suspected deaths by suicide recorded in NSW, compared with 537 suspected suicide deaths recorded during the same period in 2021, 506 recorded in 2020, and 504 in 2019. In short, the tip remains pretty much the same.

What about the middle?

Data from hospitalisations in the past few years have shown an increase in the rate of self-harm hospitalisations in some states, but not others. In 2020–21 there were approximately 29 900 hospitalisations due to self-harm in Australia.

While the state-by-state data are mixed, what is clear is that the rates of hospitalisations have increased rapidly for young people over the past decade across Australia. From 2008–2009 to 2020–2021, AIHW data indicate that there has been a considerable increase in the rates of hospitalisation for self-harm for young people aged up to 24 years. This increase has been seen across the adolescent population, but has been particularly pronounced for young females.

For example, there has been a threefold increase over this 13-year period in the rate of self-harm hospitalisations for females aged 14 years and younger to approximately 71 hospitalisations per 100 000 (up from 19). Similarly, the rate of hospitalisations for females in the 15–19 years age group has almost doubled, now at 698 per 100 000 (up from 374).

What about data from the bottom layer?

Estimates from the new National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing data suggested that a total of 393 700 people self-harmed over one year. When comparing these new data to those of hospitalisations described above, we see that the number of people who reported self-harm over past 12 months was more than ten times greater than that of people admitted to a hospital. Of those reporting self-harm, 271 000 were women, reflecting a gender difference consistent with the hospitalisation data. Young people and young women are again disproportionately represented in these figures, with one in 14 females (7.0%) aged 16–34 years reporting self-harm in the past 12 months.

Figure. The self-harm iceberg. Within a 12-month period, a total of approximately 393 700 Australians reported self-harm, approximately 29 900 were admitted to hospital for intentional self-harm, and approximately 3100 died by suicide. Data are approximate in that they were collected at different times, using different methods, although each represents a recent period of 12 months. The self-report data do not include children under the age of 18 years, but the hospitalisation data do. The self-report data do not exclude individuals contributing to the hospitalisation data. Nevertheless, this double reporting is unlikely to change the shape of the iceberg.

What’s driving these trends?

These data prompt us to ask at least two questions:

- What are the causes of the proportionately large representation of young people in the hidden parts of the iceberg?

- What can we do to prevent or ameliorate what might well be a worsening situation?

Years of research suggest that the causes of self-harm are complex, cumulative and unique. Abuse, drug and alcohol misuse (for men), and domestic violence (for women) have been identified as triggers. But, in this area it is hard to distinguish triggers that lead to an incident of self-harm from underlying “root” causes. Often the best understanding we have from research is identifying some factors associated with self-harm, such as mental ill health, which are unlikely to be the root cause.

In recent years, our view has shifted fundamentally, now recognising that suicide and self-harm cannot be due entirely to psychologically or biologically “faulty” factors within the person, and are better understood, perhaps in the most part, as a result of biological factors in association with social and economic conditions, such as unemployment, financial strain, poor housing, and poverty, that make people and communities vulnerable.

If we consider young people, there are at least two possibilities that may contribute to the rising rates.

Either youth-specific factors, such as increased competition for tertiary education places, more challenging entry-level job requirements, and increased employment precarity, have made life more difficult in the past decade. Alternatively, universal factors, affecting all of us, may have been experienced more intensely by the current cohort of young people because of their developmental stage, or their past experiences of life until now (ie, the current cohort may include more refugees, a greater proportion of people from marginalised communities or those who have experienced multiple traumas). Looking at the effects of COVID-19 over the past years, which was associated with an exacerbation of this rising trend, the data suggest (and here) that universal factors such as uncertainty and lockdowns may have greater effects on young people than did youth-specific factors. COVID-19 disrupted many normal developmental milestones of adolescence – such as building peer and romantic friendships, expanding independence, establishing careers and shaping future identities – and it exacerbated inequalities in the demands placed on girls and women across household and schooling responsibilities.

This is not the place to argue the toss as to the potential factors that caused the decade-long rise (factors such as social media, financial stress or helicopter parenting), but the issue certainly points to the need for more comprehensive data.

What are the trends in societal and economic factors that mimic self-harm and hospitalisation rates over the past decade and through COVID-19? Can we use publicly collected datasets to assist in testing some causal hypotheses, or at the very least, falsifying some? What contributes to the variation in rates in different regional locations, using geospatial mapping to pin down protective and adverse factors?

We should also ask young people, particularly women and girls, why they are harming. A recent review we conducted on paracetamol poisoning revealed that we have no Australian current research findings on the views of the public around motivations for self-poisoning and self-harm.

What should we be doing now to intervene?

Clearly, we should be offering treatment and assistance to those who reach hospital. But, more importantly, the new findings compel us to “see” and address the “unseen” bulk of the problem. As the self-harming might be less severe at the bottom of the iceberg, we have the option of prevention, at the community, school and policy level.

At the school and community level, we already have readily implementable solutions. The Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) program in schools, has been shown in both Australia and overseas to reduce suicide ideation. It is not “rocket science” to suggest that this might be implemented in all schools in Australia.

A recent smartphone application also developed by Black Dog Institute showed reduction in suicidal ideation, with young people working themselves through it without professional expert help. Making it free and readily accessible seems like a good step.

We need to go broader than advances directed at individual children, adolescents and young adults and think about solutions at the policy level. In recent years, we have been impressed by the reductions in suicide in male adolescents that can be achieved by changes in legislation around same-sex marriage. The support of young people through JobKeeper, JobSeeker and Youth Allowance during COVID-19 likely prevented an increase (here, here, here, here) in suicide rates. More recently, research from the United States confirmed that greater experience of “everyday discrimination” during COVID-19 increased suicide ideation tenfold. This suggests that action to reduce stigma and discrimination may be powerful.

Contrary to some views, thoughts and attempts of suicide are not mild or benign. Self-harm is one of the strongest risk factors for suicide. In youth, ideation and self-harm set up a potentially risky life path, which is associated with loss of productive years of work and affects communities and families for decades.

In the short term, we need research to better understand the causes of self-harm, its fluctuations, and how youth are differentially affected. We can also implement what we already know works in self-harm.

Shifts in the geopolitical world landscape, threats to democracy, rises in constant communication of bad news, inaction on climate change, and uncertainty are all likely to increase in the next decade. Even in the short term, the effects on the mental wellbeing of our future cohorts will be substantial, in terms of human costs, family impact and, ultimately, economic prosperity. We must act urgently.

The Black Dog Institute will be holding the Summit on Self-Harm on 10 November in Sydney.

Scientia Professor Helen Christensen, AO, is a Professor of Mental Health at UNSW Sydney and a Board Director of Black Dog Institute. She is a world-leading expert on suicide prevention and self-harm.

Associate Professor Aliza Werner-Seidler is Head of Population Mental Health Research at the Black Dog Institute. She leads a program of research in youth mental health including the prevention and early intervention of common mental illness.

Dr Natalie Reily is a Policy Officer and Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Black Dog Institute.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Self-harm is a sign that something is really wrong with our culture. Families and communities are being broken down and the support system which would normally wrap around and support our adolescents are not there. Instead the “support systems” are empowering children with their “rights” and breaking the vital bonds with their parents in the ignorant belief that this is what our teenagers need. No – they need a strong, healthy family and community to provide the teenagers with unconditional love, encouragement and the healthy boundaries teenagers desperately need.

If you want to reduce self-harm work out the rot cause – and it is broken families and communities.

I was in my mid-twenties when I started to self-harm and this continued on a regular basis into my mid-thirties. Until I found something that felt the same but didn’t require visits to the Hospital or GP to be sutured or the rare occasion surgery. Tattoos. This helped and I stopped self-harming for almost 15 years. Unfortunately in 2020 at 51, the 4years leading up to that, I experienced/survived more abuse and Trauma. which did nothing to help with my PTSD and other mental health issues. I came to a major hospital in Perth WA. I had no memory of self-harming or overdosing let alone being intubated and airlifted from the country hospital to RPH in Perth.

Angry at myself is an understatement when I realized that I had self-harmed.

The one thing that no Psychiatrist/ Psychologist, Nurse, or allied health professionals asked about or talked about was the self-harm and multiple suicide attempts in those first 5 years of initially being admitted to the psych ward. I spent most of those 5 years in and out of the hospital mostly in secured wards.

My biggest issue was the whole mental health system prefers to over-medicate its patients or physically corner, manhandle or physically restrain them in one way or another and just outright abuse them. There seem to be no human rights for the mental health patient. And in the public mental health sector over the decades in and out of the mental health system, I have lost count of the dozens and dozens of Doctors Psychiatrist, Psychologist including med students you see, that literally rattle off the textbook questions that are required to give them an idea what category you fit in the DMS5 and give you a diagnoses/label. Rarely do they listen to what you are telling them or asking them and they are defiantly not taking notice of what you don’t or aren’t comfortable talking about. I have found throughout the decades if you have mental health issues you apparently are a moron with no ability to question or critical think. We need to expand peer to peer

work placement & training. Another idea is to have people with lived experience involved with clinicians on panels/boards that are integral to policy and procedure updates and changes. Medical boards, legislation committees, submitting summations for changes within the senate and cabinet.

This article made a few things come to the surface…

I was a child of parental child abduction and parental alienation at age 11. Cut off from my mum by my dad and isolated thousands of miles away. By age 12, I was cutting my legs with a metal ruler. Not enough to cut deeply, but just enough to release the emotional pain. This was during the mid-’80s. I had never heard of self-harming before or seen anyone else do it. There was something within me that made me want to cut myself. Like I had no control.

By age 14, I moved into obsessive exercising, a new form of self-harm that many people often think exercising is a form of self-care. Exercising sometimes 4-6 hours a day. It was like I was physically punishing myself, another form of self-harm to get me through each day, something I could control, something to wear me out so I could sleep, and something to release the pain.

From age 14 to 22, I battled with bulimia nervosa. I was eating so much food to fuel my body with all the exercise, but my father criticised me for eating so much. I then started to feel bad. I would eat and then bring it up. I felt like I wasn’t normal. I didn’t fit into this world. I had to keep everything a secret. There was a lot of shame. No one knew my battles.

There is a happy ending at age 49. I now live a happy and normal life. Free from self-harm and free from emotional pain.

Hey ‘Anonymous’ gutsy share, I have traveled through a similar landscape – probably the hardest/scariest time of my life and I’m glad I’m still here!

A lot of us don’t reach out for help when we need it but are very happy to help others!

I’m a fan of exercise too and sorting stuff through on my own but without sounding preachy I just want to say that if you find a good counsellor it can not only bring help and relief when you need it but lead you to find strengths and positives that make life easier and happier going forward. Helped me anyway and it’s just a very tough place to go through alone.

Anyway I’m glad you got through and wish you all the best.

I would add trans-generational and collective trauma, but the big issue in young people (and older) is the climate crisis, as evident in local, national and world-wide weather emergencies, with only worse to come unfortunately, so suicide prevention will become truly difficult.

I am now old(ish). I n my late teens to mid twenty’s I had a LOT of confrontation with this demon. I would threaten myself, the sweat would flow and I would relent. Especially when I went to bed at night. Once I was sitting in my broken-down car with a loaded rifle in my hands, soaking with sweat.

Eventually I decided these threats were simply messing up my life. I said to myself:”Either get out of bed and do it now, or NEVER revisit this subject.” I put myself on the spot and proceeded to sweat as much as ever. My main guidance was 1) there were some critics who I did-not want to please, and 2) a few supporters who I didn’t want to hurt. After a while I made the demanded promise to myself and remember feeling really freed.

Subsequently there have been some dark days when I was tempted to renege, but I have always avoided suicidal thoughts since.

I didn’t ask for help as I would never want to burden another with this problem which was mine. I maintain that attitude to this day. I was interested to read of sufferers using a self help app. Maybe they have the same attitude.

Was I mentally ill? That would imply that when I made a promise to myself, I was suddenly cured, so I doubt it.

Was I attention-seeking? I didn’t ever tell anyone.

Might I have ever done it? Possibly when dark days came. I think it was more than a self-flagellation.

Do I think I am a rare case? No, there are many who fall short and have to cope with the reality, and work past it.

More tips? Yes, enough physical to sweat for a while (eg jogging) has been v. helpful