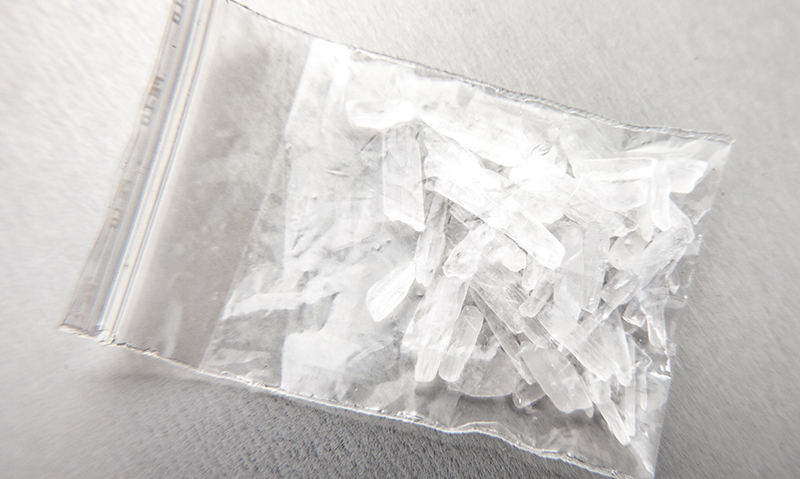

EXPERTS say that calling ice use in Australia an “epidemic” is alarmist, but agree that the current health care system is falling short of adequately managing addicted patients.

Professor John Fitzgerald, drug and alcohol expert at the University of Melbourne’s school of social and political sciences, told MJA InSight that while timely intervention was essential, “GPs have to find the entry point into the system to get the best matched services for the patient”.

However, there was no one-size-fits-all care system for people with methamphetamine addictions.

“It’s a hard slog to try and work around a system that is clumsy at best and at worst an impediment,” he said.

Professor Fitzgerald was commenting on a study published today in the MJA which estimated there has been increase in the number of regular and dependent methamphetamine users in Australia over the past 12 years.

The authors estimated that during 2013–14 there were 268 000 regular methamphetamine users and 160 000 dependent users aged 15–54 years in Australia. This equated to population rates of 2.09% for regular use and 1.24% for dependent use.

The rate of dependent use had increased since 2009–10 and was higher than the previous peak.

- Podcast with Professor Margaret Hamilton

- Related: MJA — Recent warnings of a rise in crystal methamphetamine (“ice”) use in rural and remote Indigenous Australian communities should be heeded

- Related: MJA — Trends in amphetamine-related harms in Victoria

The highest rates were consistently among those aged 25–34 years, for whom the rate of dependent use during 2012–13 was estimated to be 1.50%. There was also an increase in the rate of dependent use among those aged 15–24 years.

These estimates highlighted the substantial rise of regular methamphetamine use in Australia, the authors noted.

They observed that best practice in treatment involved intensive application of structured psychological and behavioural therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapies and contingency management, but this was not well translated into practice.

“Ongoing engagement in treatment and improved access to evidence-based treatment options are essential for improving the health of dependent methamphetamine users,” the authors wrote.

In an MJA podcast, former executive member of the Australian National Council on Drugs, Professor Margaret Hamilton, said that methamphetamine addiction was not as scary as the mainstream media made out, but it was a significant and complex problem. This was due to crystal meth being readily available and fairly cheap, having high purity, and the fact it could be smoked, which made it seem like a less serious drug to take.

Nicole Lee, consultant psychologist and associate professor at the National Drug Research Institute at Curtin University, said that “while there hasn’t been an increase in the number of users per se, those who are using now are using more potent forms and more frequently, which has resulted in more problems, including dependence”.

Professor Lee told MJA InSight that the main challenge with methamphetamine was that while a lot of people who use it do not become dependent, once a person is addicted it is an extremely difficult drug to get off and stay off, partly due to the long-term brain effects.

She said that people who use methamphetamine were more likely to present to their GP when they first experienced mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression and sleep issues, as opposed to disclosing their addiction.

“Some careful questioning might reveal a coincidence with weekend drug use.”

Professor Hamilton agreed, but said the fear being stirred up by the media was making GPs doubt themselves and feel ill-equipped to manage ice addiction.

However, she said it was important to highlight to GPs there were no “special tricks” for treating this group of people.

“Do a screening assessment, do a physical assessment if you can, do a mental health check, and follow through.”

Professor Lee said that for people who have developed a dependence syndrome, there was a range of inpatient, outpatient and ambulatory detoxification options, as well as referral to outpatient counselling or inpatient rehabilitation. “Withdrawal is not a successful treatment on its own, with nearly everyone relapsing within a few months.”

Professor Hamilton said that unfortunately, there were simply not enough drug and alcohol specialists in the country to deal with methamphetamine addition.

“[That’s why] I encourage all medical professionals and anyone else involved to use their skills and knowledge of responding to a person they are concerned about.”

She said that GPs needed to ask their patients about substance use more routinely “in a non-judgemental and respectful manner as they have learnt to ask about other activities”.

Professor Lee said that prescribing medications to treat the mental health symptoms of ice use was an option, but there is little guidance or recommendations for GPs about how to avoid problematic drug combinations such as antidepressants, other stimulants, opiates and long-term use of benzodiazepines.

“Nearly all methamphetamine overdoses have other drugs involved, and many of those other drugs are pharmaceuticals, so care and thorough assessment is required in prescribing.”

more_vert

more_vert

I’m concerned about the stories of extreme violence that have been associated with ice and the numbers of anecdotal accounts of people off their faces posing acute danger to those immediately nearby.There are times when Big Brother should be much more involved with provision of Psych help and or creating jobs for younger suitable support in the field ?house call?trainees”(as a suggestion-noBoydt just leave it to the law enforcement-Some Leadership akin to earlier closing of central boozeries!