It would be tempting to think that the problem of coronary heart disease has been solved.

The likelihood of an Australian man or women dying as a consequence of coronary heart disease is a quarter of that seen fifty years ago, and a person admitted to hospital with a heart attack is alive at one year after the incident around 95% of the time. These improvements are largely due to advances in public health, especially reduced cigarette smoking, and better treatments for people with established heart disease.

Impressive as these figures are, they hide many truths. With a growing and ageing population, the overall burden of coronary heart disease continues to grow and coronary heart disease remains the single leading cause of death in Australia. Furthermore, this dramatic improvement in outcomes is unlikely to continue in the face of emerging risks including the growing prevalence of obesity and diabetes. Stark inequities also lie under the headlines; most notably in Australia is that between the ages of 40 and 60 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are 4 to 5 times more likely to die of coronary heart disease than other Australians.

These are local observations of a genuinely global problem. The recently published Lancet commission on rethinking coronary artery disease was grounded in this evidence. Modelling performed for the commission and based on current trends in global burden of disease statistics, found that the number of deaths from coronary heart disease will continue to grow towards 2050 and that annual health care spending on cardiovascular disease will increase by more than 50% from 2021 levels to over $2.5 trillion globally.

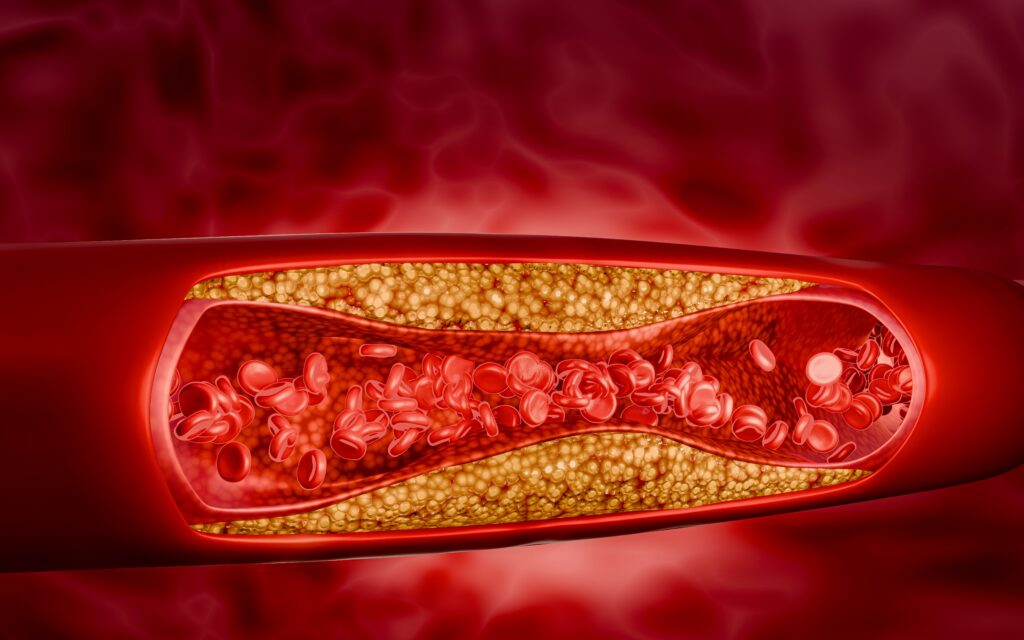

The commissioners argue that these trends are not inevitable but to reverse them will need us to rethink our approach to coronary heart disease. Fundamental to this is the recognition that coronary atherosclerosis, the cause of most coronary artery disease, is a preventable condition.

For decades the primary approach for coronary atherosclerosis in health care has focused on treating acute and chronic ischaemic heart disease; late manifestations of the disease process, after atherosclerosis has usually been developing for many years. This is comparable to abandoning vaccination for infectious disease or waiting to treat cancer only once it reaches an advanced stage.

The central message of the commission is the need to refocus on atherosclerosis as the cause of the disease, long before the late manifestations of advanced disease from ischaemia. The commissioners argue that a change of definition is required; classifying the condition as atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (ACAD), thus moving away from the emphasis only on the recognition of ischaemia.

Every ischaemic event has the potential to have been prevented. Taking this argument further, these events can be seen as a failure of prevention, and not an inevitable consequence, of ACAD. The commission models show that if all metabolic and behavioural risks were eliminated by 2050, these trends could be reversed and more than 80% of deaths could be prevented. An aspirational goal maybe, but one that is evidence based and should be, at least in part, achievable.

The commission identifies many opportunities to achieve its goal to “not just manage symptoms and events but to prevent the disease from developing in the first place and, where possible, reverse its course.”

While future research will doubtless lead to more effective preventive therapies, and potentially eradicate atherosclerosis, significant gains could be achieved simply by increasing the uptake of existing, evidence-based therapies known to improve outcomes. ACAD is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death and is often the first manifestation of the disease. For these individuals, prediction of risk, earlier diagnosis of ACAD and preventive therapy is the only potential pathway to survival. In those who do reach hospital alive, a recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report using linked administrative data found that only 12% of patients with acute coronary syndrome received coronary revascularisation and remained on four classes of secondary preventive therapies at 12 months after admission. While administrative data cannot determine the precise reasons and appropriateness for this lack of persistence with secondary prevention therapies, they offer potential targets for further research and implementation.

In common with many high-income countries, Australia lacks a systematic approach to screening for early coronary atherosclerosis even though advances in non-invasive coronary imaging (principally cardiac computed tomography) render this feasible. Identification of appropriate target cohorts for screening will be required and research is needed to determine how traditional approaches to risk prediction can be enhanced using novel biomarkers, including those from genomics, health-related “big data” and routinely performed non-cardiac imaging.

Health services face constant pressure to use scarce resources wisely to deliver best outcomes. A shift to earlier detection and prevention of ACAD requires evidence-based health policy, driven by health service research to determine how these approaches can be successfully implemented and scaled up in a sustainable way. Public health policies, workforce planning and research into health systems are all needed to deliver improved outcomes in a cost-effective and sustainable manner. These policies, including research funding, should be proportionate to the burden of disease and appropriately targeted.

The problem of coronary heart disease is not solved, but thinking differently can get us closer to that goal.

Listen to the MJA Podcast with William Parsonage and Sarah Zaman.

William A Parsonage reports a leadership and fiduciary role within the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Sarah Zaman reports grants from Abbott Vascular and personal fees from Novartis and Boston Scientific.

Stephen J Nicholls reports grants from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Anthera, CSL Behring, Cerenis, Cyclarity, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Resverlogix, New Amsterdam Pharma, Novartis, InfraReDx, and Sanofi-Regeneron; personal fees from Amgen, Akcea, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Kowa, Merck, Takeda, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Vaxxinity, Sequiris, and NovoNordisk; is listed as inventor on the patent for effects of PCSK9 inhibition on coronary atherosclerosis; has a leadership and fiduciary role with Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand; and is director of Evidence to Practice (non-profit meeting company).

Rasha K Al-Lamee reports grant support from the British Heart Foundation; personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Fondazione Internazionale Menarini, Shockwave, Cathworks, Medtronic, Philips, and Servier Pharmaceuticals; and board participation for Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Cathworks.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

What more do you need to research to advance a policy of early screening???? It’s funding allocation for screening that you should be advocating for and not more research. A program to offer every person 50+ a full blood panel and visit to GP would be a massive public health screening boost and not just for early detection of heart disease. Based on that data, then I think it would be legitimate to guide more specific research. And please don’t argue cost – the reduction in hospital days would justify the cost – perhaps ask a couple of health economists. Cheers

I agree with the article, but when you talk about big data or AI, you can’t ignore AutocathFFR, the only true AI-based FFR on the market, already showing strong results and a high adoption rate. It’s clearly on track to lead this category very soon

Thank you for a concise thoroughly informative article complemnted by the “Lancet Commission on rethinking coronary artery disease”

I had read the Lancet’s report and as you noted is grounded by evidence.

As a mother of boys now young men, advice should equally be addressed to both men & women. Social media impact often causes confusion with plethora of influencers

Such an important point, Oliver. We might also pause to consider our ‘confidence interval’ around cause of death. A cardiac cause is an easy default for those completing death certificates, perhaps particularly in the elderly. If we are being even more sophisticated, we might give serious thought to our conflation of ‘risk factor ‘ and ’cause’, which is rife and perhaps at least to some extent unavoidable. Not that I disagree with reasonable steps to reduce the burden of atherosclerosis!

The issue is not just cause of death at any age, because we are all going to die of something, but causes of premature death, however we choose to define “premature”, for example, under the age of 70 years or under the age of 80 years.

We are probably less concerned about a preventable condition that kills only or mainly people over 99 years old than about a condition that kills only or mainly people under 50 years old.