This week, the MJA published new evidence of the national prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV). The survey of a representative sample of 8500 Australians adds new knowledge about the prevalence and nature of physical, psychological and sexual violence between intimate partners aged 16 years and over in Australia. The study confirms that substantial proportions of Australians have experienced physical violence (29.1%), sexual violence (11.7%), and psychological violence (41.2%) by an intimate partner. These findings are relevant to a range of policy makers and sector stakeholders, and are significant for medical practitioners and regulatory bodies.

IPV is gendered. Men’s experiences of IPV should not be ignored, but significantly higher trends among women clearly demonstrate areas of unmet need. This survey confirms that intimate partner violence is a gendered phenomenon, particularly if we look at patterns of abusive behaviours. One in eight women in Australia (13.6%) have experienced all three types of IPV (by either the same partner, or across different relationships), compared to 2.9% of men. In addition, women are significantly more likely to experience each type of IPV than men. There is even higher IPV prevalence among people in same-sex relationships and those of a diverse gender. This is of particular concern as these populations are under-researched and have received limited attention in policy and practice.

Young people experience high rates of IPV. Our study also found that IPV is common early in life. Half of young people aged 16 to 24 years (48.8%) had already experienced some type of IPV; significantly more than older people aged 45 years and over (39.9%). Among young women aged 16–24 years, one in four (26.8%) experienced physical IPV, one in four (25.8%) experienced sexual IPV, and half (48.4%) experienced psychological IPV. This is extremely significant, since these young people need these experiences identified and responded to in order to prevent further abuse, violence and harm.

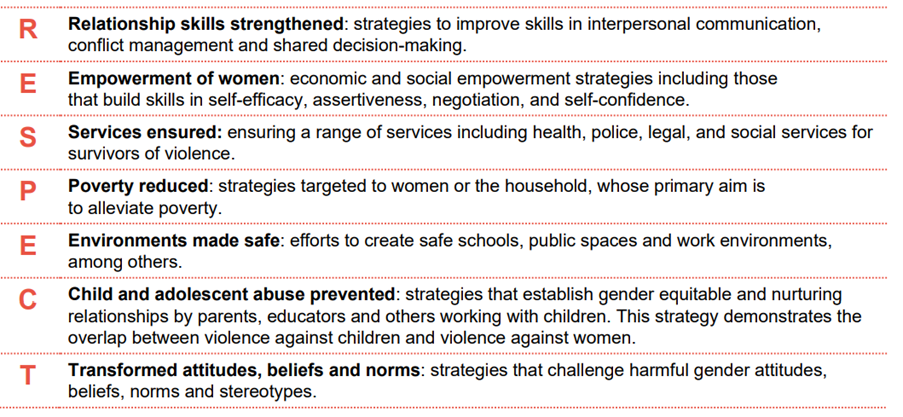

Broader prevention needs. Australia needs to do more to prevent intimate partner violence across the Australian population. Improving prevention of IPV requires steps at societal, community, institutional, and individual levels. The World Health Organization has identified prevention areas in their RESPECT Framework below (Figure 1).

Supporting the RESPECT Framework, a 2024 Australian rapid review of evidence-based prevention approaches suggested a focus on children and young people as victim-survivors in their own right to ameliorate future trajectories of harm. We know that one in four people witness adult intimate partner violence as children. Childhood experiences of IPV between parents increases the likelihood of subsequent adult victimisation, and of people inflicting violence against their partners. If we could provide early intervention for these families, we could break this trajectory.

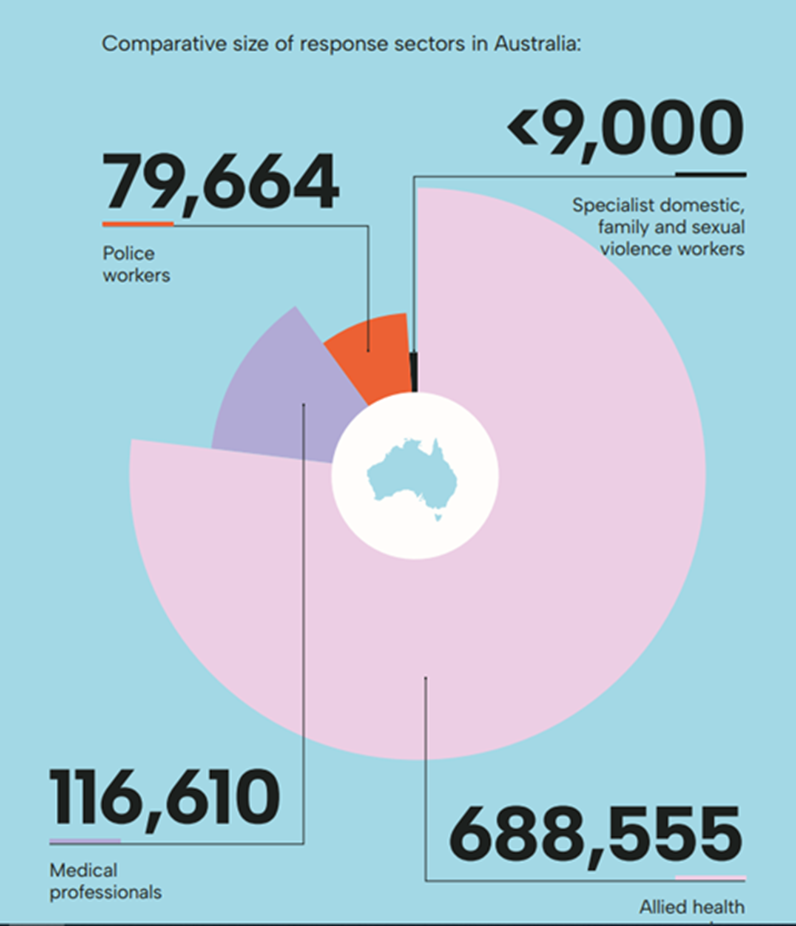

Activating the health system. The health system is perfectly placed to contribute to this work, but health students in universities are not being given adequate training in this area. Activating the health system, a recommendation by the rapid review panel, involves equipping and resourcing practitioners to engage early, particularly in primary care and mental health settings. They are the largest available response sectors identified by the Domestic, Family and Sexual violence commission 2024 report (Figure 2).

Health practitioners, and in particular general practitioners, are the highest professional group told about intimate partner violence. When they are sufficiently trained and resourced, these practitioners have the skills to place individuals and families on a pathway to safety and wellbeing. The Australian government is investing in this area through the Safer Families Centre and Primary Health Networks but more needs to be done in the health system to support clinicians in their role in supporting those who experience IPV, and assisting in downstream prevention.

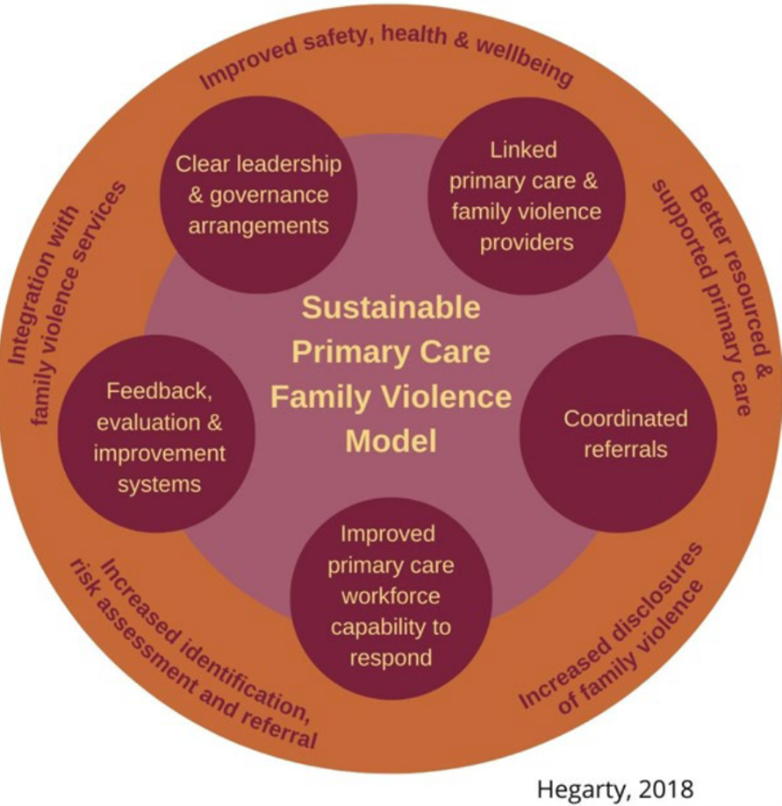

This includes implementing a sustainable primary care family violence model (Figure 3).

Key elements of the model are:

- Clear leadership and governance arrangements required for system change.

- Linked primary care and family violence providers by practice support from a clinical lead and a family violence worker undertaking secondary consultations.

- Coordinated referrals by engaging a network of primary care and specialised organisations (family violence, sexual assault, child protection) in a geographical catchment to deliver a joint response. Clear referral protocols and pathways coordinated by the family violence worker will ensure all members of the family are guided to seek help.

- Improved workforce capability through whole-of-organisation based support, resourcing and primary care training (by the clinical lead and family violence worker) to improve knowledge, skills, and confidence of both clinical and non-clinical staff to identify and respond to family violence.

- Feedback, evaluation and improvement systems essential to any sustainable program, ensuring that constant improvements are shaped by timely feedback and local evidence.

This new evidence of IPV prevalence requires acceleration of supports for the health sector and for practitioners as part of a comprehensive national strategy to support existing plans. Policy, procedures and practitioner education across Australian health sectors can make an immense contribution to identifying those who have experienced IPV, providing necessary clinical supports, and collaboratively engaging other systemic measures to prevent continuance of IPV and break intergenerational cycles.

Read the research in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Kelsey Hegarty is a professor of family violence prevention at the University of Melbourne and the Royal Women’s Hospital. She leads the Safer Families Centre focusing on interventions to prevent violence against women through early identification and response to domestic, family and sexual violence in health care settings.

Ben Mathews is a professor in the School of Law at Queensland University of Technology, specialising in multidisciplinary research into child maltreatment. He is lead investigator of the Australian Child Maltreatment Study, which included an additional section measuring the prevalence of intimate partner violence.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Dear Kelsey, this is such an important article which summarises how prevalent IPV is and how impactful clinician care in general practice can be. The findings regarding IPV in young women comes as no surprise given the online influencers promoting the ‘manosphere’ and promulgate the notion that gender equity programs are displacing men from their rightful positions in society. Violent behaviour is a choice and also a learned response. Thank you for your endless advocacy to address intimate partner violence across all sectors of society.

Perhaps this is something MyMedicare could become involved in to assist Primary Care in identifying and managing IPV. The PHN is also well placed to assist s it does with mental health but unfortunately often through layers of bureaucracy