With the Total Fertility Rate dropping in almost all nations, the world’s human population is expected to fall spectacularly in the next few hundred years, writes Dr Will Cairns in Part One of this series.

That we humans are quite good at short-termism is scarcely surprising, given our origins from within the natural world. Our struggle was to survive the year, and we were dependent on the cycles of the seasons and our ability to extract a living from our surrounds. History was communicated by word of mouth, stories morphed into legends, then myths, and became the foundations of our beliefs.

For those not well versed in modern science, predictions about the future based on studies of old rocks and complex assessments of the instability of a dynamic planet can seem so obstruse that we commonly default to assume that humanity will persist on a trajectory determined by our personal beliefs and experiences.

As a result, we have been so slow to respond to the global changes that the sheer quantity of humanity has caused to our planet (see The Conversation, 9 Feb 2024). We now find ourselves struggling to minimise the disastrous consequences of doing too little too late.

As we will see shortly, while our demographic problem of excess seems to be self-correcting, few have looked over the summit of the world’s human population in about 2085 to what lies beyond 2100 CE. And almost no-one has begun to address the challenges that will be posed by what we find there (to be discussed in Part 2 of this article).

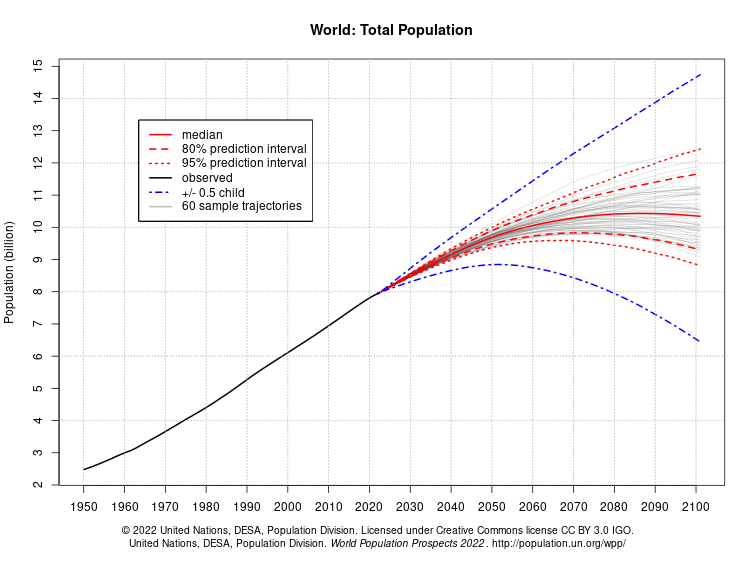

When I was born in 1949, the world population was about 2.5 billion (here). Since then, it has risen to over 8 billion and is expected to peak at about 10 billion in 2085 (here), when the current cohort of infants will be reaching our retirement age.

Before I go any further, there are a couple of definitions we need to understand:

- Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is the average number of children born to a woman over in her lifetime.

- Replacement rate is the level of fertility, the TFR, where the number of births per lifetime per woman maintains a constant population. In any community, it depends in part on the number of deaths in childhood and young adulthood — in the developed world, where early mortality is low, it equates to a TFR of about 2.1.

If the TFR is higher than the replacement rate then the population rises. If lower, it falls.

The current surge in global population has come about over just the past few centuries because we have been so successful in stopping people from dying, both by reducing child mortality and by managing disease and delaying death in old age (here), while persisting with a TFR that evolved to match high childhood mortality.

The reduction in mortality began with the onset of the industrial revolution. In the middle of the 19th century, about one-third of children born in England died before the age of ten years. By the time I was born about 100 years later, this had dropped to less than 5%. Similarly, the next third of those born in the mid-19th century who had died before the age of about 65 years now lived into their 60s and beyond. These changes were obtained first by public health measures, such as better housing, better nutrition, improved sanitation and clean water, and, more recently, by vaccination, obstetric care, antibiotics and other disease prevention and management. We are now at the point that very few of us in the developed world die before the age of 65 years (here), and the past two centuries of increasing average life expectancy is starting to flatten out as most of us approach our individual maximum possible lifespan.

When childhood mortality declines, women do not have to have half a dozen or more children to produce two reproducing adults. Parents soon realise that they and their surviving offspring have better lives and are more successful if they do not have to share the bounty of the parents’ effort with many siblings.

As the impact of the industrial revolution has spread across the globe, communities have become healthier and childhood mortality declines, and women in particular are more empowered, better educated and increasingly engaged in the workforce. With only a modest delay, and when effective contraception becomes widely available, communities worldwide have adapted their fertility to compensate for higher numbers of children surviving to adulthood, and their TFR has declined rapidly (here and here).

From the mid-1960s, this became a worldwide phenomenon, other than in a few societies (eg, Niger TFR 6.3 and Israel TFR 2.94, here and here) and some subcultures within larger communities (eg, here and here). The annual global number of human births peaked in about 2023. With the previously steady increase in average life expectancy plateauing, global population growth is about to stop abruptly (Figure 1).

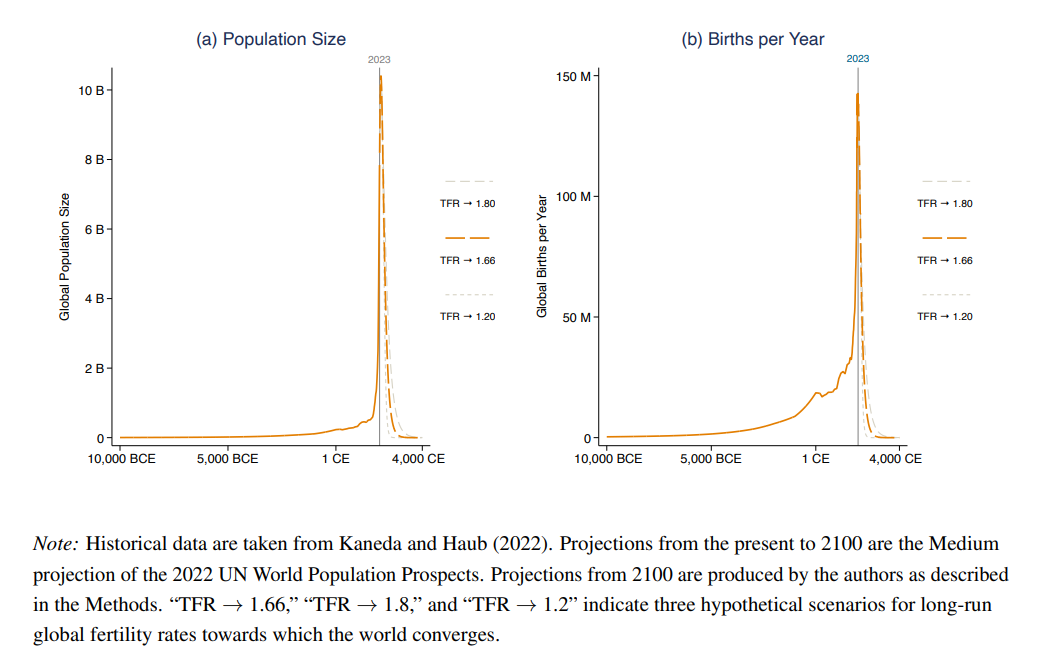

While this does graph might cause us to feel relieved that the human population has finally plateaued, as we all know, a very small segment of a curved line looks like a straight line. Figure 1 can also be understood as the peak of the curve of Figure 2 (a) and the product of Figure 2 (b), which has been copied from an article by Spears and colleagues that I recommend that you read. The world’s population of humans is about to plummet because, over the past 60 or so years, the global TFR has dropped dramatically to well below the replacement rate and continues to decline.

Most people now live in countries where the TFR is less than 2.1, including the largest India (2.07) and China (1.45). In some of these places, where fertility is already less than replacement, the population will continue to rise for a bit longer due to population momentum — when the age distribution is skewed to younger people, the consequences of a falling TFR take time to work their way through the population structure.

Other nations, such as the United States (TFR 1.84), the United Kingdom (1.63) and Australia (1.73), have maintained or increased their total populations only with high levels of immigration. Other nations that attract few migrants, including some of the largest (eg, China and Japan), are already unable to sustain their population size from within their own community.

No nation that has had its TFR drop below 2.0 has ever seen it rise back above 2.0.

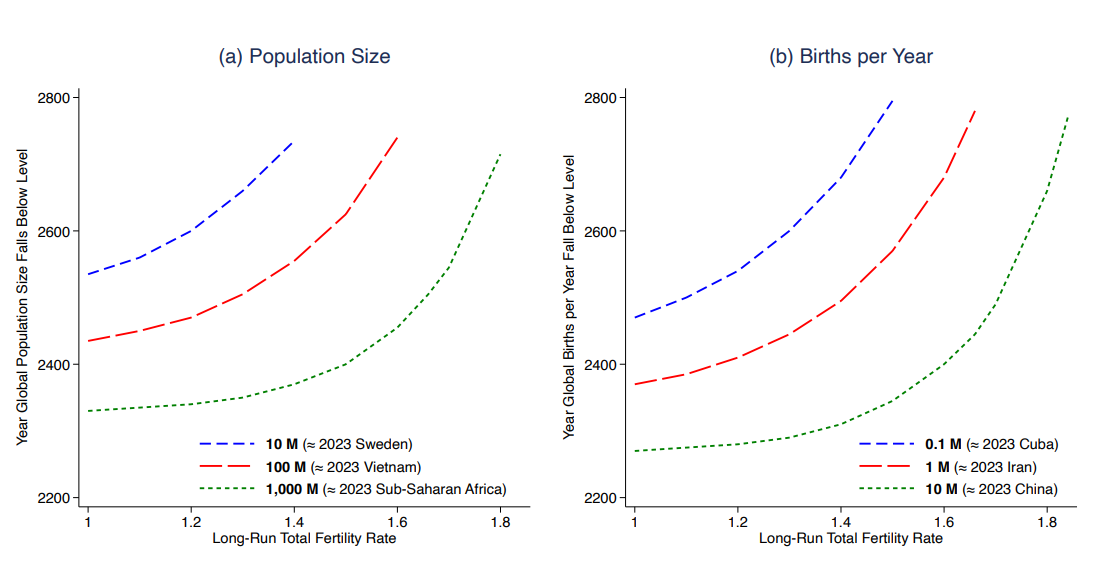

So, within not too many hundreds of years, and depending on the TFR, there are likely to be less than one billion people alive, and possibly only one-tenth of that, lower than it was 10 000 years ago.

Alternative scenarios in which the TFR eventually rises to replacement levels produce a range of projections for an eventual “stable” population size, depending on when the TFR rise happens.

These simple projections for the future of the human population do not offer much room for doubt, other than if the TFR increases dramatically and unexpectedly. They are the product of relatively straightforward calculations using well substantiated methods and accurate data about which there is little uncertainty. Not unlike predicting journey times for various train speeds. There are almost none of the unknowns, known or otherwise, that surround predictions of the weather, economics or global climate change. Nonetheless, the projections from the United Nations and from Spears and colleagues did include ensembles of trajectories to account for a variety of scenarios of TFR (see Figures 1–4, and my earlier InSight+ article here).

It also should be noted that such projections also presume constancy in other more disruptive and less predictable domains. They have not attempted to address major disruptions to the size of the human population that might ensue from catastrophic global climate change, a decimating pandemic, and/or perhaps even global conflict and a nuclear war.

So what does this mean for humanity?

I will start with an immediate consequence that has implications for health care and aged care that you can mull over while you await the publication of Part 2 of this two-part series.

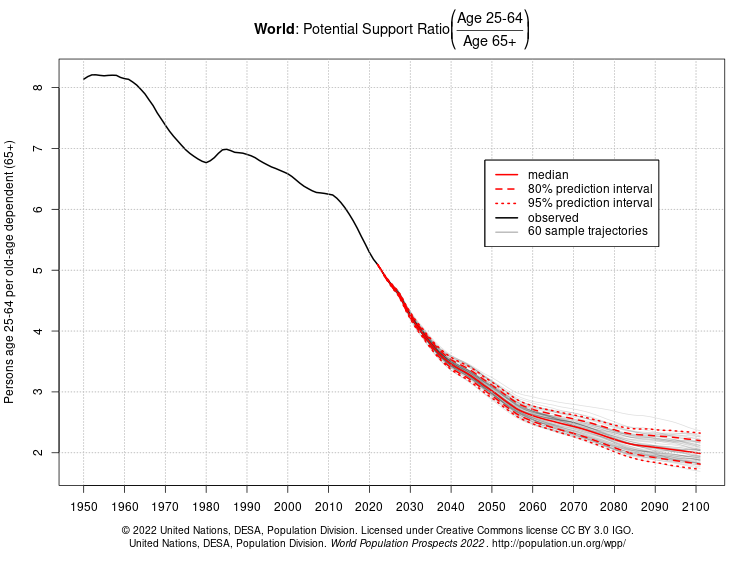

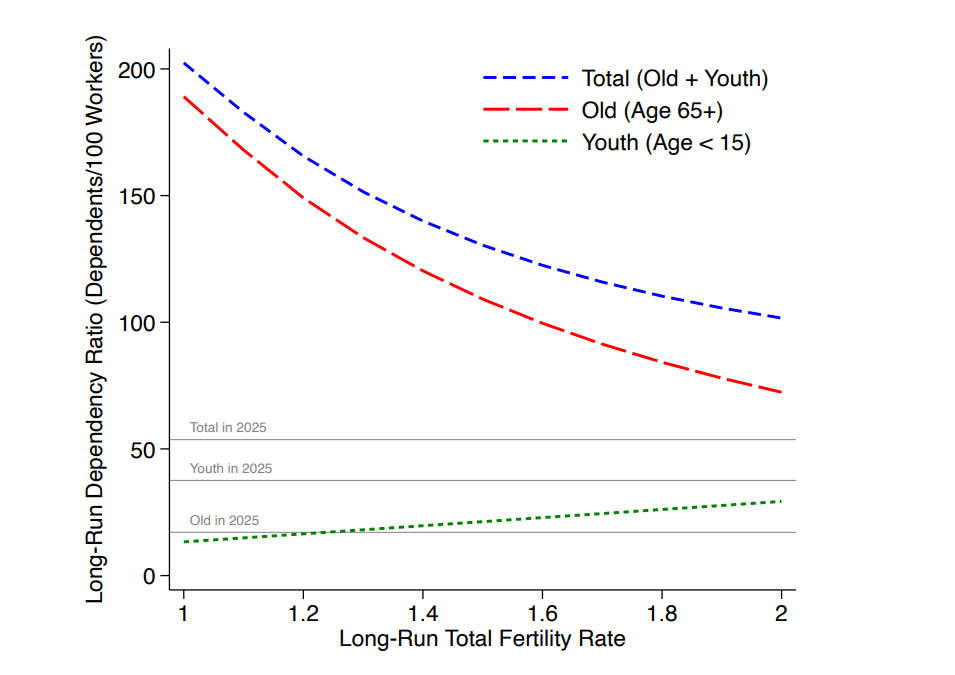

Both the Spears and the UN documents also considered dependency ratios – the numbers of people who require support compared to the size of the rest of the community who support them, both with resources and by their labour. These are indicators of the challenges posed by a plummeting population that are already becoming a major issue in many nations.

Looking again at UN global data (Figure 4), when I was born in 1949 there were about eight people of working age (25–64 years) for every person over the age of 65 years. The booming of babies like me who are now the elderly was just starting and there were fewer elderly people than now because the average life expectancy was less than 70 years and fewer treatments were available to prolong the diseases of ageing.

Seventy-four years on, globally there are now about five adults per old person because so many of us live on into extreme old age. By 2100 CE, when the children born in the first third of this century are elderly, and with a low TFR for the rest of this century, this ratio is expected to have dropped to about 2. In other words, when my grandchildren are elderly, the world will have only about two people alive aged between 25 and 64 years for every person alive over the age of 65 years.

However, remember that Figure 4 describes the plateau at the top of the population curve (Figure 1) up to 2100 CE. Thereafter, for hundreds of years, as the world’s population drops like a stone (Figures 2 and 3), the ratio of workers to dependents (Figure 5) will remain very low at about 1:1 for the mid-range long term TFR.

This little collection of graphs and commentary poses sobering challenges to us all.

Throughout all of human history until very recently, many children died and few of us reached what we now call old age. The past century or so has been an aberration. The population has boomed because most of the children produced by a high TFR survived into adulthood, and the majority of us do not die before we reach old age. We have now almost completed our rapid transit across this ephemeral state to the entirely novel phenomenon of low fertility with a high proportion of people living into old age and approaching their maximum possible life expectancy.

Assuming the continuation of the current trajectory of our fertility and mortality (and even with some variation), the exponential population growth of the mid-20th century (doubling time of 37 years) is about to flip to an asymptotic decline, with the population halving every about 40 years.

The hard realities of these demographic projections will pose huge challenges for humanity. The circumstances within which our biologically and culturally driven human behaviours evolved are now becoming part of our past. And our economies, local and global, that emerged as shaped by the context of what we imagined to be endless opportunities for growth are about to run into the wall of demographic and environmental reality on a finite planet.

We are approaching the other side of the plateau and, unlike patrons who have purchased tickets for a roller coaster, few of us have given much thought to what we are likely to face when the human population falls over the edge.

In second half, Part 2, of this short commentary on the future of the world’s human population, I will explore what this might mean for us.

Dr Will Cairns has retired from clinical practice as a palliative medicine specialist.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

From an Indian standpoint:

Pronatalism – encouraging people to have more children, is extremely dangerous.

We are in the middle of a Holocene extinction event, and the earth is stretched to its limits.

Don’t believe right wing propaganda blindly. Most countries with low birth rates are doing very well

economically, while most countries with high birth rates are doing badly (MOST!). It is the quality of

human resources that counts. There is a population composition fallacy we must understand. Deciding on the number of children is a personal affair, and governments don’t have a say here. Trying to raise birth rates artificially has mostly never worked. Even if it is done, it may have unintended consequences like increasing the supply of unskilled labour, particularly in cases such as India. The theory of demographic dividend has also been criticized severely, and has many limitations. It will also send out wrong signals to other states which are grappling with high population growth. Instead, improve the quality of education which is deplorable to say the least – this is the government’s priority, and most Indian state governments are not doing their job. Also focus on skilling

and vocational training. Treat low fertility as the new normal, and change economic development models accordingly. There is also a chance that fertility rates will increase slightly if societies become more prosperous. Please read my papers by typing Sujay Rao Mandavilli in google search.

Assuming we do not have a environmental or other catastrophe, which is a big assumption, surely the population will stabilise and technological advances will change the needed ratio of young to old.

My moneys on a disaster though as the population peaks and ever scarcer resources are fought over. Whether humanity survives is unknown.

“Old people will keep working longer” … If someone will employ them !!

I agree. I don’t think that 65 is “old” anymore for working, when the majority of work is now not hard physical labour. Even retired people with significant superannuation have their money still working and earning – ie. they are not dependent yet on young workers.

Also, some have predicted that we may have reached “peak health”, due to increased obesity and DM2 rates, and that life expectancy will soon fall.

These factors (and others) make it hard to predict the future. We will need a smaller human population to survive in a future world limited by ‘resource depletion’ (WWF calculates we are now using 1.8x the renewable biological/ecological resources of the planet each year). Somehow, we will have to survive the future that we have contributed to making.

Reducing global inequality may assist in reducing the global population peak, and the steepness of the cliff to be fallen off.

Old people will keep working longer .