HUMAN life expectancy will increase to 150 years within this century. Really?

When I was a GP I used to visit my frail elderly nursing home patients in my lunch break. Frequently I found them fast asleep in front of Days of Our Lives. This gave me pause for thought about how we live out our final years.

In the past few weeks it has been interesting to see a number of commentators suggesting that before the end of this century the advance of technology will enable some people to live on to the age of 150.

Among the evidence cited for this is the observation that the average life expectancy has increased from about 40 years to 80 years in the past 150 or so years and that this trend will continue.

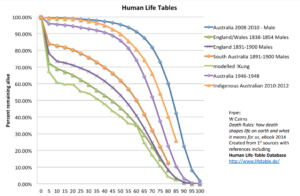

The facts tell us otherwise. This Kaplan–Meier graph drawn up from several different life tables shows the proportion of the population who have remained alive over the 100+ years from their birth.

Over the past 200 years or so the application of scientific discovery — public health measures, improved nutrition and, lately, disease treatment — have almost stopped us from dying as children and prolonged our lives as mature adults.

However, our numbers plummet as we approach 100 years of age because all of these interventions make no difference to the reality that we eventually wear out and die. Apart from the odd unverified outlier, only one person has ever been confirmed as living for more than 120 years.

Life tables for the US dating back to the 19th century show the limits of modern technology to deal with the failings of old age:

| US white males | 1850 | 2005 |

| Life expectancy at birth | 38.3 | 77.4 |

| Life expectancy at age 50 | 71.6 | 80.7 |

So, in the past 150 years, in the most powerful nation in the world with the best that modern technology and affluence can throw at the challenge, while the average life expectancy at birth has risen by 39.1 years, the life expectancy of a 50-year-old has increased by only 9.1 years.

It used to be that the highest mortality was among children; now it is among the elderly. A man aged 65 years living in the UK in 2004‒2006 could expect to survive for another 16.9 years, of which 10.1 years (59.8%) were deemed to be healthy.

| Life expectancy of 65-year-old males in UK | ||

| 2004-2006 | 2007-2009 | |

| Total | 16.9 years | 17.6 years |

| Disability free | 10.1 years | 10.2 years |

While the life expectancy of a 65-year-old man increased by 0.7 years between 2004‒2006 and 2007‒2009, the healthy life expectancy has increased by 0.1 years. Most of the recent change in life expectancy has been that sick men are having their life with sickness prolonged.

There have always been at least a few people who avoided fatal infections, childbirth, accidents, wars, worn-down teeth, cancer, heart disease, or even just wearing out earlier, and have lived to be more than 100 before they slow down and die.

More of us become centenarians now because we don’t die of other things earlier, but there has been no significant increase in the maximum time that people can remain alive.

For most of us our maximum life expectancy remains less than 100 years, and for some far less. There is no evidence that modern technology has been able to stop even people who get no particular disease from just grinding to a halt when their time is up.

We have not been able to put more sand into our hourglass to increase the number of the days of our lives.

Talk of living to 150 is a distraction. The real challenge for the community as a whole is to accept the inevitability of death and to reintegrate that acceptance into culture.

As health workers and health care managers, we can all play a vital role in that process, both in how we communicate our understanding of death as a normal part of life and in how we incorporate it into the care of our individual patients.

Associate Professor Will Cairns is Director of Palliative Care in Townsville and author of the eBook Death rules — how death shapes life on earth, and what it means for us.

* Australia 2008-2010 – Males

USA 2006

England/Wales 1838-1854 – Males

South Australia 1891-1900 – Males

Sweden 1816-1840

Modelled !Krung

Australia 1946-1948

more_vert

more_vert

Amazing article love the graph. I would love more articles, especially on some of the new fangled extreme ideas to stop aging. Pay a couple of grand to be put into a cold chamber? No thanks, tried it when I couldn’t pay my heating bill. Fast to live longer- people already doing without food in some countries and I am not sure whether that’s helping them age well.

However in the USA you can still get to be president as an old dude with dementia, so lots of job opportunities there.

Couldn’t agree more! We all have a “best before” date and as health professionals we should be educating people and communities to enjoy quality of life rather than striving for length of life. My wonderful mother has slipped into severe dementia over the past 5 years and the journey for all of us is gruelling.

Thanks Will for providing the data that underpins what so many in the general, clinical and scientific community already knew. It is unfortunate that the outer reach of current science fiction was brought into a very important economic and demographic discussion on the increasing proportion of older people in the population over the next 20-30 years especially, while the baby boom wave passes through. That wave should be waning by about 2050, rather than the scenario being painted as the burning platform by our political leaders. Indeed, by then the platform will be gone, and the need is to deal with the issue starting now, rather than painting horror stories for a time may of us will not see. Eventually there may be a increase in maximum life span, but no currently available evidence supports that this will occur in the lifespan of anyone currently alive!

Great article.

Problem with old age today, is that people still think of it as 100 years ago. Retire and vegetate in front of the TV, or help raise the grandchildren to relieve the boredom.

I hope I’ll be different, but with rheumatism and asthma from a very young age, I’ll have other things to worry about.

My father, my mother and my mother-in-law all lived to be over 90. None of them had any quality of life after about 85 or so. I’m 67 and already starting to see the bits starting to fall off. Ditto with my friends in their 60s and 70s. Not looking forward to 85, let alone 100+.

Now, that is what I call a survival curve. Fantastic article.