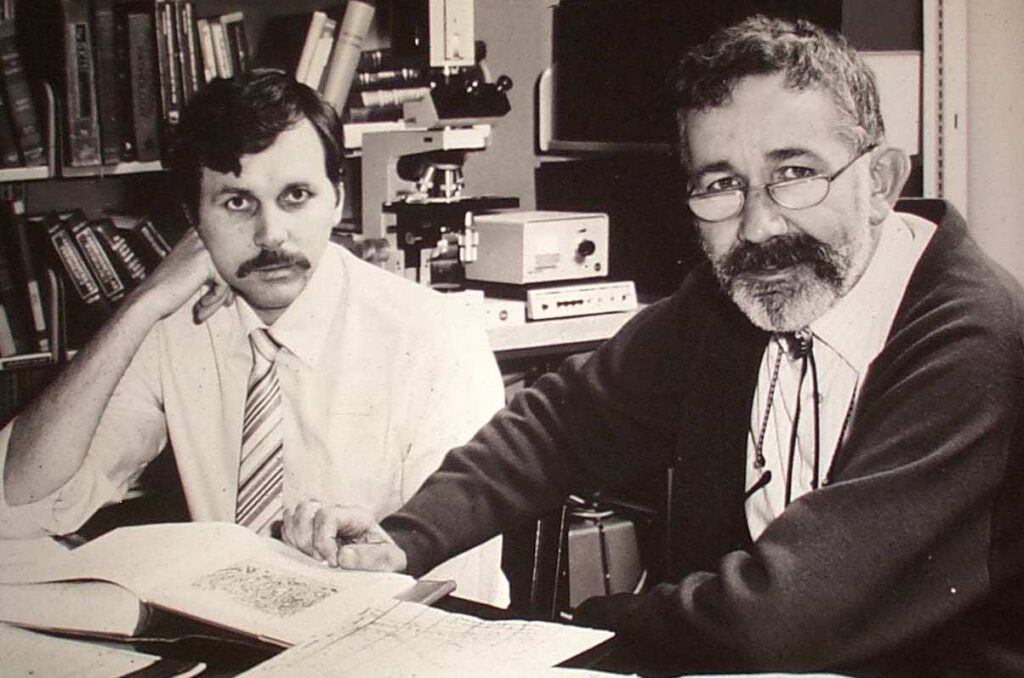

Meeting Robin Warren changed my life. Our work together began the most significant work of my career. He was also my friend for 43 years.

Robin’s Nobel Prize winning work began on 11 June 1979. He was examining a stomach biopsy specimen that was affected by gastritis, a condition easy to diagnose because of the various white cells (“polymorphs”, “pus cells”) present in the tissue. Very few doctors in the world were interested in gastritis because it was common and believed to not cause illness. There was no treatment, and it was even thought by some to be a natural ageing process. Robin, being always curious about the unexplained, asked for a silver stain, which would show up any bacteria present.

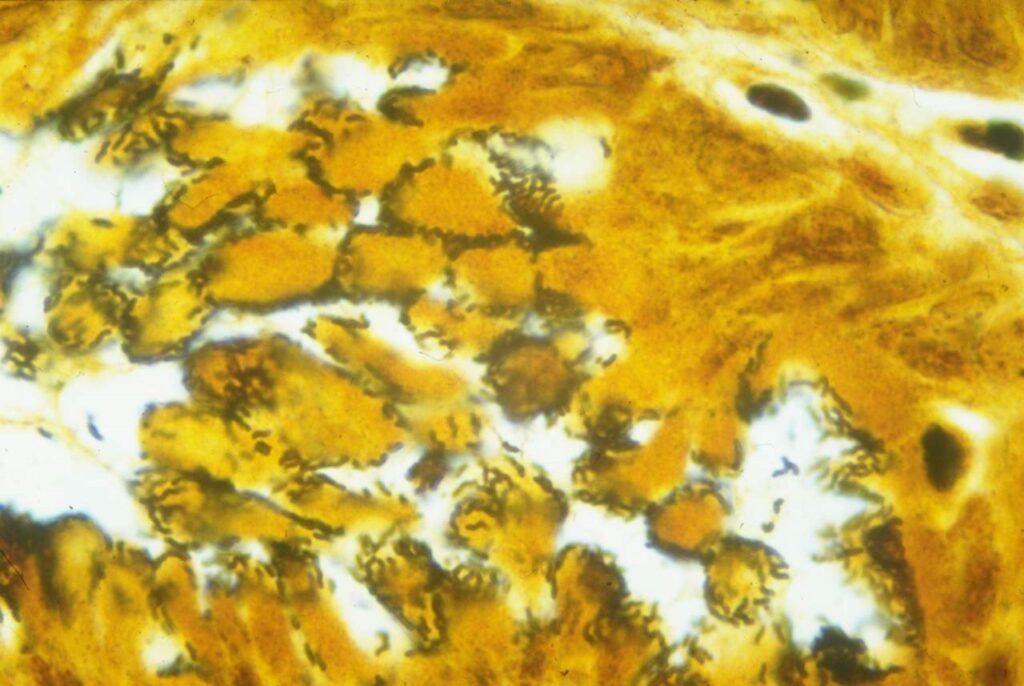

Curiously, the surface of the stomach was covered in curved black bacteria, probably 30 organisms on every epithelial cell. Robin drew some excellent pen and ink drawings of characteristic changes he saw under high magnification. The photograph he took that day, and the illustrations he drew, have never been improved on and have been reproduced in hundreds of textbooks and journals.

After 1979, Robin started looking for more cases of the bacteria and found that it was not rare, if the correct samples were taken. This meant fresh material from endoscopic biopsy, preferably away from any ulcers present, rapidly fixed and carefully oriented before microscopy. He showed the bacteria to his colleagues in pathology who, I suppose, all had their own work to do, and they blamed the bacteria on contamination. It was known that fibre-optic gastroscopes were difficult to sterilise and one expert in the UK had identified these bacteria, incorrectly, as Pseudomonas, a common inhabitant of plugholes, drainage tubes and now, probably, endoscopes!

The beginning of our work together

By July 1981, Robin had collected more than 20 cases of the bacteria and he had asked my boss, Tom Waters, if someone could collaborate with him to study these patients to see if there was any associated disease. Tom sent me down to meet Robin. On Robin’s list was a patient whom I had looked after earlier that year, so I was immediately interested. Also, curved bacteria called Campylobacter were a hot topic in 1981 and were supposed to come from chickens.

I made an appointment with Robin and then, for the rest of the day, I was educated about these curved bacteria. As well as microscope slides of them, Robin had his detailed drawings of the various features. He also pointed me to a few pathology books in which gastritis was described, and even found a couple of rare cases where the bacteria had been shown. I then collected the medical records of the cases with the bacteria, and we spent weeks trying to see what diseases these people had. Initially, we could not see any pattern. A few had ulcers, but all kinds of disorders were present. It seemed that anyone could have the bacteria.

Like Robin, I was mesmerised by the colourful stains and the high resolution images of the bacteria. The absolute clarity and authority with which Robin could describe the bacteria and the stomach histology, can be seen in his recorded lecture on the Nobel Prize website. That is exactly what he showed me on that first afternoon together in July 1981.

During the next four months, we collected biopsies from as many patients as my gastroenterology bosses had time for. We could soon see the curved, Gram-negative (pink) bacteria on fresh Gram-stained specimens, but for six months they could not be cultured.

After consulting with Robin, I treated an elderly Russian man who had incurable stomach pain with a vague diagnosis of “intestinal angina”. After two weeks taking tetracycline, his chronic pain was completely cured, and Robin could see that the stomach bacteria were greatly reduced.

Robin mentioned that there were similar bacteria reported in cat stomachs in old veterinary pathology books. I followed this lead and found in the references several descriptions of stomach bacteria going back 100 years. But as with our first 20 patients, no correlation with human disease had been made. We now knew that teachings that the stomach was sterile because bacteria are killed by acid, were wrong. These new bacteria were apparently immune to strong acid. Robin believed that by burrowing into the stomach mucus layer, the curved bacteria could avoid the acid and multiply in their own micro-ecological niche. A completely new concept.

The study begins

We needed to study patients without the bacteria and contrast them with patients who did have the bacteria. Robin requested biopsy samples 5 cm away from any ulcers because the ulcer healing process would appear a lot like gastritis. So, we planned a prospective study of 100 consecutive patients undergoing endoscopy. We wanted to culture the bacteria, find out how it survived in the stomach, and see if we could find it in people who did not have gastritis.

In April 1982, with ethics approval and consent forms ready, I studied consecutive Royal Perth Hospital endoscopy patients. In each patient, a gastric biopsy was sent to Robin for histology, and another was sent to microbiology for Gram stain and culture, while I immediately recorded the endoscopy findings. Robin scored the biopsies for gastritis (polymorphs, mononuclear cells, and mucosal cell damage) and also for the presence of curved bacteria. The microbiology laboratory tried to culture the suspected Campylobacter-Like-Organism (CLO) as it was called. At this stage, we still had not connected the bacteria to ulcers. The study thus was prospective and blinded, with each set of laboratory or clinical data hidden from the other investigators.

In September 1982, the results of the study were sent to us by the statistician. Robin was excited! When the bacteria were present, gastritis was seen. When the bacteria were absent (40%), there was no inflammation. Curiously, all the duodenal ulcer patients and 80% of the gastric ulcers were associated with gastritis and bacteria in the stomach, far away from the ulcer. Of interest to me was that 60% of patients had the bacteria, but of those with duodenal ulcer, 100% (13/13) were infected. So, the bacteria were strongly associated with peptic ulcer, especially duodenal ulcer.

Working backwards, it seemed that it was almost impossible to have a duodenal ulcer if the bacteria were absent. Therefore, if we could eliminate the bacteria with antibiotic treatment, we could probably cure ulcers.

“Nerds who love technology”

Core to Robin’s personality was his love of mathematics and attention to detail. The association between the bacteria and gastritis was apparently incalculable. The mainframe computer at the university used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), but this package could only calculate Chi-Squared to five decimal places so it always gave a result of “p=0.00000”. Robin really wanted to know how strong the statistic was (smaller being better). He abandoned the mainframe and purchased the latest Hewlett Packard 11c calculator, which could handle very large numbers. According to Robin, the p value on the association with the bacteria was about 10-12 (p=0.000000000001). We both felt very satisfied. I started collecting HP calculators after that as a hobby! It’s a coincidence that the final name of the bacteria settled at Helicobacter pylori, which also has the initials HP.

We submitted our early work as letters to The Lancet but these took more than five months to be published, in June 1983. The editor, Ian Munro, had been unable to find any reviewer with knowledge of gastric microbiology.

Robin’s and my letters contained beautiful pictures of the histology and the electron microscopy with some speculation that the bacteria could cause peptic ulcers and stomach cancer.

We then tried to write up the full paper for The Lancet but this was a slow process, taking many months. Robin and I have some similarities in our personalities, we are both nerds, both love technology. But there are also major differences in how we work. Robin was older, an established consultant with more experience and very aware of the historic importance this paper would have. He wanted it to be perfect and unable to be criticised. I was younger, enthusiastic and passionate. I wanted everything included — all we had proved and all we knew based on my extensive knowledge of past research into historic descriptions of these bacteria. Finally, towards the end of 1983, after months of re-writes, our wives intervened. Win Warren and my wife Adrienne scheduled a meeting at our home in Mount Hawthorn where we would not be allowed to leave until we had agreed on a final version of the paper. Towards the end of the night, Win and Adrienne banished us and they decided on the final wording of the discussion and conclusion of the paper. The Lancet editorial office accepted it with the changing of not one phrase, and it was published on 16 June 1984 with 4500 citations since then.

After that, my wife Adrienne and I travelled with Win and Robin to receive international prizes. The first was the Warren Alpert Prize at Harvard Medical School in 1994, and the second was the 1997 Paul Ehlich prize in Frankfurt, which was the last time Win was in good health.

Interest in Helicobacter had grown exponentially after the 1994 National Institute of Health “Consensus conference on Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease ” was held in Washington and the BBC documentary called “Ulcer Wars”, directed by the late Michael Mosely, was released globally.

Fish and chips and a Nobel prize

The day that the Nobels were announced was memorable. In his retirement before the Nobel prize (1997-2005), we would only meet up once or twice per year. We would have dinner at the Swan Brewery Pub on the river below King’s Park on the Monday evening when the Medical Nobel Prizes were announced, always after 5 pm on the first Monday in October. This went on for several years until finally, on 3 October 2005, we were halfway through our beers and the fish and chips were arriving when Robin’s phone rang. A Swedish voice announced that he had won the Nobel Prize. The second half of the message was that Dr Marshall also won it, but they could not locate him, and they were forbidden to publicly announce the winners before actually telling them by telephone. Robin’s reply was “Dr Marshall is right here at the pub with me. Here, I’ll put him on!” So, he handed me the phone, and all was well. But the Nobel committee were very concerned that Robin and I were already at the pub celebrating, even before we had officially been told. Had the secret Nobel committee been infiltrated and the news leaked? They were reassured after hearing our nice tradition of going to the pub anyway.

Robin had a full program at the Nobels. I remember well the interview we gave at a round table with the CNN anchor. I had made the comment that, as Nobel laureates we were expected to be knowledgeable and have respected opinions on all kinds of subjects. So, the compere decided to test Robin and, without any preparation or warning, asked “So Dr Warren, what do you think of the global trade deficit?” to which Robin immediately replied “Well, that is an illogical and meaningless question. When one country exports another country imports, so the deficit is always zero, so it doesn’t exist!”. I was impressed!

During the Nobel Prize, Robin and I participated in an “Australian Story” documentary called “The Winners Guide to the Nobel Prize” directed by Mark Gould and produced by the ABC. One of the funny scenes was Robin’s daughter-in-law Marie, who accompanied him on the trip to Sweden, when, according to Marie, referring to meeting travel deadlines, “Robin can sometimes be a little difficult”. We all knew that a meeting or a meal with Robin would never finish without a deadline.

Robin’s early life

Robin was born in 1937, into a winemaking family in Adelaide, but there were many doctors on his mother’s side of the family, so it was quite natural for him to like medicine and the sciences. He was educated at St Peter’s College in Adelaide, which has a very prestigious list of “old boys” including two other Nobel Prize winners, Lawrence Bragg, for x-ray crystallography; and Howard Florey, for the curative effect of penicillin. Robin was good at mathematics and liked the logic of the sciences, so he went into medical school in Adelaide, and then became a pathology trainee in Melbourne, until finally being recruited to Royal Perth Hospital as a consultant pathologist in 1968, by the legendary Professor Ten-Seldam.

During those years, two major events occurred that changed his life. Firstly, in his final year of high school, he developed grand-mal epilepsy. He had occasional seizures after that and was required to take phenobarbital, a drug with many side effects. This must have made it difficult for him to study and would have restricted some of his activities. However, his mother had a mature attitude to the illness and made sure that he still participated in most activities, and he was never restricted by having a disability. Against some advice from well meaning but uninformed family and friends, Robin finished school and attended university. As a young man, he was never a natural athlete, and was always a bit of a loner. He was happy to pursue his interests such as bike riding, photography and art. He continued to have occasional seizures throughout his life, even falling off his bike and breaking his hip once. Having epilepsy must have been quite a mental burden for a young person starting out in life, unable to drive a car, and being somewhat dependant on others to rescue him from episodes.

The second life-changing event happened in his internship. He met another medical student, Winifred Williams (Win) and they married about a year later. Four children came quickly in the next few years, (John, David, Andrew and Patrick) but Win managed to finish her residency. Rebecca was born later, and Win went on to a career in psychiatry.

Later life and retirement

Robin never recovered from the tragedy of losing Win to pancreatic cancer in 1997. She died as he was beginning to receive recognition for his groundbreaking work. Win was always Robin’s greatest support, both professionally and in life in general. She worked with him on his research, giving advice and editing his papers.

In retirement, Robin remained active, corresponding and visiting various cities to give lectures, usually with a family member to help him with the travel.

The Western Australian Government supported Robin’s activities for ten years from the Office of the Nobel laureates at The University of Western Australia. During that time, Robin maintained a busy working life in WA, nationally and internationally. His family and staff travelled with him to support this work.

In recent years, Robin’s ability to live by himself in north Perth was precarious because his unsteadiness worsened, and he had several falls, ultimately breaking his arm and then his collarbone. Then, in 2022, he suffered a severe bout of COVID-19, after which he remained in care until his death on 27 July 2024.

He leaves behind a proud legacy.

Robin’s legacy in WA is well recognised. Robin Warren Drive was named at the entrance to Fiona Stanley Hospital. The new medical library on the QEII medical precinct was named the Robin Warren Medical Library. In the front tutorial and reading room, you will see a portrait of Robin done in 2021 by Perth artist Jenny Davies.

(John) Robin Warren was a unique and brilliant man who improved the lives of many millions on the earth, and many millions to come.

Barry Marshall AC FRACP FRS FAA is an Australian physician, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Professor of Clinical Microbiology and Co-Director of the Marshall Centre at the University of Western Australia

Adrienne Marshall, (BA Hons Psych (UWA), BA Hons Fine Arts (Curtin U) Dip Ed.) contributed to the article. Adrienne is presently a Voluntary Gallery Guide at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Adrienne and Barry have been married since 1972 and live near the University of Western Australia.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Hi Barry-a really GREAT article-fascinating! I read your entry in the Nobel Museum in Stockholm where you also mentioned Dr Tom Waters. Head of Gastroenterology at RPH when you started as a Registrar in 1981. It was he who suggested you get involved with Dr. Robin Warren on gastric biopsies because of the frequent finding of spirochaete-like organisms. He and I were classmates at Medical School in Brisbane 1950-1955. He died a few years ago. I also have had Helicobacter pylori and have had 2 gastric cancers removed endoscopically in 2015 & 2017 with no recurrence. Congratulations on a fascinating article on your work with Warren which has revolutionised gastroenterology.

Hi Barry–a really GREAT article-fascinating! I read your entry in the Nobel Museum in Stockholm where you also gave credit to Dr. Tom Waters, the Head of Dept of Gastroenterology at RPH when you joined as a Registrar in 1981-who suggested you get involved with gastric biopsies because of the frequent finding of spirochaete-like bacilli in such biopsies. He and I were classmates at Medical School in Brisbane 1950-1955.Glad you mentioned his role in this article! Tom died in Perth a few years ago.

I also had helicobacter pylori in my stomach and have had two invasive gastric cancers removed endoscopically by Dr. Michael Bourke FRACP in 2015 and 2017 with no recurrence since. Congratulations!

Thanks for your fine tribute to your friend and colleague Barry.

Vail Robin Warren.

Barry, “ I am holding the slide in my right hand with my thumb over the lable”! This was how Prof Ten Seldam insisted we start describing a pathology slide when we were medical students. He had a first class pathology department with Barry Walters and Byron Kakulas which many of us didn’t give credit to at the time, only being interested in scraping through the exams. No doubt this contributed to the environment Robin and you worked in at RPH at that time. I finished my internship at RPH in 1966 and then went overseas, so missed all the fun. Thankyou for writing this fascinating article.

I’m one of those patients who was cured through your great discovery.

I’m very grateful and very inspired by your great work.

As a consequence of your great work I believe that Perth’s intellectual flame has been graciously lit and will burn brightly far into the future for its people and for this great city.

I will not forget.

“It’s a coincidence that the final name of the bacteria settled at Helicobacter pylori, which also has the initials HP.” I absolutely adore the small details like these. And I also enjoyed the last few paragraphs about Dr. Warren’s life- you rarely get to learn about the men themselves who make amazing discoveries like you two did. He seemed like a fine man with a wonderful family.

Adrienne and I are very satisfied by the final product of this article. I’m sure Robin would have liked it too. At least one of the images has never been published before.

Thank you Annika Howells at Med J Aust

Barry Marshall

Can the Marshalls please confirm who recalled and contributed the most detail about the circumstances leading to and the last push to produce the final version of that paper to be sent to the Lancet?

Another missing link is what Robin Warren thought or said when Dr Marshall decide to ingest HP to produce an animal model (Dr Marshall’s part of the story had been well publicised and retold!)

Just wondering and pushing some buttons, I guess.

I love this narrative of the background to one of the greatest gamechanger in approaching “factoid” in which long held beliefs and generalisations are being challenged scientifically in modern times.

As a Registrar at RPH 78-81, I well remember Robin, he made pathology essential entertainment, his ironic wit caused Clinicians to tremor . The inscription on the wall said it all ” De mortuis ni nisi bonus dicendum est.”

Great article.

Thank you

What a wonderful story Barry! Thank you for sharing these personal insights and phenomenonal photographs of Robin; I never knew he had epilepsy and did not know of his passing until now; I’m not sure how many Nobel Prize notification calls have been caught on camera, but they must be vanishingly few!

I personally read your and Warren’s article on “unidentified curved bacilli” during the Lancet bicentenary year (2023), when I was going through a group of their most famous articles. I immediately realised from reading this (and also about your self-experimentation case) that I might myself have H. pylori gastritis! Despite my busy schedule, I went to get tested with a urea breath test (also developed by Robin) which came back strongly positive and have since been treated and cleared of the infection. So it is thanks to you and Robin that I (like many others) am now H. pylori free!

I was delighted to read this story today and will share it with my colleagues.

Rest in peace Robin.

Thank you for your bio, Barry Marshall. Robin and I were good friends in our youth at St Peters College, where we were classmates, and in medical school (both born 1937) along with Win, of course. He kept his epilepsy private, which was admirable. I was unaware Robin had died, so that is very sad. We lost touch (the tyranny of distance) but like all of us, I have followed his illustrious career, of course.

With regards,

David Miller, F.R.A.C.P.

What a beautiful tribute. Remarkable work and family support notably integral. Thank you.

Medical research heroes, thank you.

You have made mine and millions of others lives better.