Around the country, private maternity hospitals are closing, with enormous implications for many Australians needing care and for the health system as a whole.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound effects on Australia’s health system, not least of which has been the enduring pressure on our public hospitals. More Australians are waiting longer for planned surgery than ever before, emergency department congestion is at record levels, and ambulance ramping is costing lives. At the same time, access problems for older patients seeking aged care mean that public hospital beds are often filled with people who do not need acute care but have no place to go outside of hospitals. Ways of trying to keep people out of hospitals — accessible and affordable general practice to manage acute and chronic health problems, and expensive urgent care centres — are struggling to keep up with demand for services.

In the current environment, it might be expected that Australia’s private hospital sector is thriving as people seek alternatives to our public hospitals. Certainly the numbers of Australians taking out private health insurance is increasing, reversing a trend of decline over the years before the pandemic. However, despite promising signs that private health insurance is enjoying a renaissance, all is not as it seems. There are concerning signs that Australia’s private hospitals are struggling to remain viable after serving our health system for decades. At a time when our public hospitals are struggling to cope, failures in the private hospital sector would strike a major blow for many Australians needing care and destabilise the entire health system.

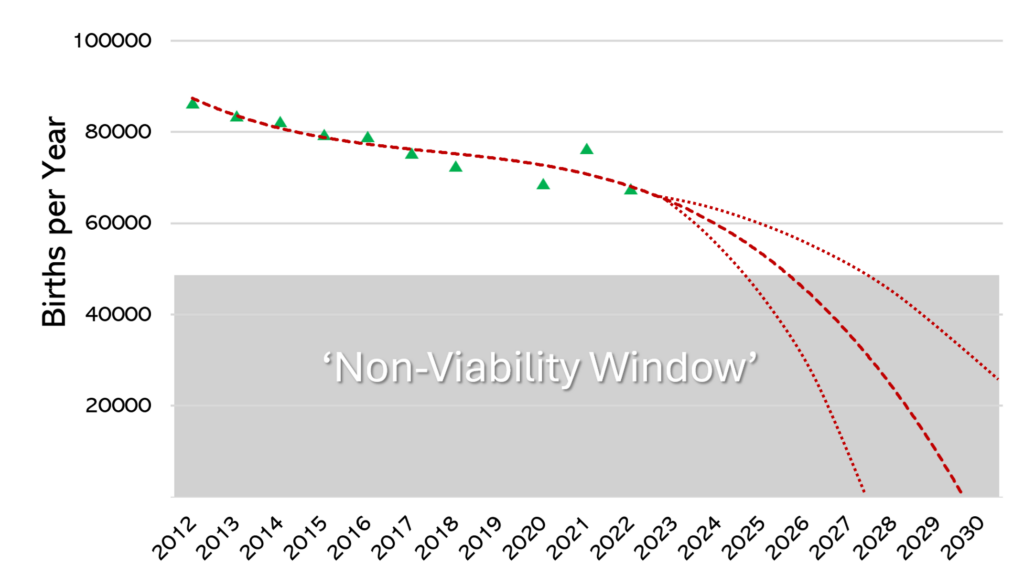

An area of great concern, and likely the harbinger, is that of maternity care. Thirty years ago, almost 40% of all births occurred in private hospitals in Australia. If women who use their private health insurance in public hospitals are excluded, it is likely that in 2024 less than 20% of births will occur in private maternity hospitals based on trends after the pandemic. In the decade from 2012 to 2023, the number of babies born in private hospitals fell by 22%. Taking into account these trends as well as falling birth rates and other societal factors, our preliminary modelling is predicting that the number of births occurring in Australian private maternity hospitals are likely to fall precipitously. So quickly that, by the end of the decade, private maternity hospitals will cease to exist (Figure 1). Such a loss of capacity has enormous implications for the health system as a whole, which we would like to explore here.

The first factor underpinning our prediction is demographics. Australians are having fewer babies with our birth rates — like those in all high-income countries — showing no sign of stabilising. The rates of decline in childbearing are steepest for women and couples in higher socio-economic groups. This is important because socio-economic status influences a person’s capacity to afford private health insurance premiums. As things stand, full reproductive health cover — including pregnancy and birth cover — is included only in gold insurance policies. Many women who do hold private health insurance still choose to birth in public hospitals. This is related partly to the attractiveness of models of care offered by many public hospitals, and also with the disincentive of out-of-pocket costs that accrue even with top-level health insurance.

A recent National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists analysis of data provided by the Department of Social Services for 2022 revealed that, of women who began antenatal care with a private obstetrician, 40% did not continue. Another factor is age, with young women — the group most likely to use maternity services — having lower rates of private health insurance cover. Statistics from the start of 2024 reveal that only 5% of all private health insurance payouts were for maternity care. Yet data reveal that women value continuity models with private obstetric care rating highly, and roughly half of births in Australia will require either instrumental assistance or caesarean section, so non-obstetrician group practice models cannot deliver true continuity for many women who would value it.

Around the country, private maternity hospitals are closing. This trend is occurring in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and Victoria. The causes of these closures are multiple but one of the key issues is staff shortages. Maternity care is labour-intensive — pardon the pun — and finding skilled staff is proving a major challenge for private hospitals. The available midwifery workforce has been falling and training new midwives takes time and resources. Providing attractive pay and conditions is difficult in private hospitals, meaning that public hospitals are becoming more competitive and attractive to staff.

Midwives are not the only group critical to providing care in private hospitals. Anaesthetists and paediatricians are essential and must be available around the clock. Difficulties in securing enough of these specialists to work in private hospital maternity rosters is recognised as one of the drivers of private maternity hospital closures. Similarly, providing care to private patients requires 24-hour commitment from obstetricians. As older obstetricians who commonly worked in solo private practice retire, a move to obstetric group practice is taking place. However, no obstetric practice can be offered if a staffed maternity hospital — with midwives, paediatricians, anaesthetists and others —isn’t available.

Private health insurance in Australia is community rated, which means that any Australian, no matter their state of health or need for care, pays the same premium with the same insurer except, as previously explained, for women wanting reproductive health cover. For this reason, making sure that a large pool of healthy people are committed to paying premiums is critical for the sustainability of the system as a whole. Among the key drivers of healthy young Australians taking up private health insurance with hospital cover are maternity and mental health care. In a cost-of-living crisis the value proposition needs to be very clear to healthy young people not only for taking out, but maintaining over a lifetime, private health insurance.

At the moment, with demographic and other forces coalescing, our modelling suggests that the viability window for private hospitals to provide the resources necessary to run maternity services (the supply side) will not be sustained by demand for much longer. With the closure of private mental health beds also playing out at the same time, the value proposition for healthy young Australians to pay for health insurance seems likely to dwindle. With fewer private maternity facilities available, especially in regional areas, even women who hold health insurance have nowhere to use it. As things stand, our prediction is of the private maternity sector rapidly running out of steam – and that is bad news across the board.

Caroline de Costa was formerly a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry, Cairns, and is now a researcher at The Cairns Institute, JCU .

Gino Pecoraro (OAM) is a Brisbane-based obstetrician and gynaecologist at the University of Queensland. He is the current president of the National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, former board chair of the Australian Medical Association and a past president of the Queensland branch of the AMA. A/Prof Pecoraro does work in private obstetrics.

Steve Robson is an obstetrician, gynaecologist and health economist. He is president of the AMA.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Having experienced care as a patient in the public & private health sector & worked as a midwife in both in the UK & Australia over 33 years I feel like I’ve got to understand middle ground regarding care, clinical outcomes, efficiency, cost & safest practice:

1 .Having a private health service alongside a free public one is very smart because both systems support each other. Eg: UK all public has gone to the dogs because overcapacity & underesorced = unsafe = patients suffer preventable harm / die = clinicians leave with moral injury & burnout.

2. Healthcare needs to reflect the public needs. Families just want what they need & not anything that costs more or keeps the in hospital longer. Caesarean sections, instrumental births, inductions & 3/4th degree tears are more painful, they affect mothers ability to care for a newborn & that really matters. But obviously we all want safe care with experts when emergencies arise as the often do.

3. Families also want to have trust in their care provider & that they won’t ‘hold on to them’ if there is a more experienced person to help them. This applies to private midwives & Drs, but also in hospital with complex women that really need a physician & an anaesthetist or intensivist & in the community with GPs. The crux of it I believe in OZ is professional politics because of the lack of understanding of what multidisciplinary care is. All clinicians have a place & can’t do each others jobs. English midwives are taught to be the expert of normal & accountable in law. English Obstetricians are the experts of abnormal, Fetal medicine fellows are interutero experts of abnormal & the system works because there are more than enough women having babies to go round. The issues are not realising the specialist knowledge, ego & fear of takeover & blame so ‘holding on occurs’ & that definatly harms patients.

4. The current state of play in public healthcare is very unsafe because of overcapacity & underesorced. Rather than addressing this situation by transferring low risk to the community with midwives & GPs what happens is clinicians escalate because they follow their APHRA codes of conduct & practice, but instead of being heard & understood they are bullied by each layer of burocracy & ostracised from their peers. So we have a massive culture of fear, blame & defensive practices. Coroners cases are repeated over & over again. But no actions taken due to no funding= REPEAT.

Solutions start with:

1. Health Ministers LISTENING currently they are breaching ALL of the Healthcare Legislation.

2. Focus on shared goals= safe care & a job for EVERYONE= put egos LAST, not 1st.

3. Reducing length of stay & numbers in public, whilst increasing in private.

Imagine…..if your sister could have everything she needed when she needed it when giving birth to your nephew. We would be pretty happy I reckon.

(Retired Clinical Midwife Consultant Birthing Services, Activist because currently it’s toxic & UNSAFE). 🧐

The Federal Government needs to consider reintroducing the MBS Safety net for obstetric care.

The rebate afforded patients for 24/7 private obstetric care is inadequate.

In addition, the relative value of the service provided needs to be adequately funded by Government.

They scrapped the Safety net in the early 2000s. but a reintroduction to maximum cap would provide patients with relief and go some way in ensuring that Obstetricians can meet the needs of running a practice and maintaining the indemnity.

In reference to a reply in this article: “Male obstetricians have provided the majority of true private care.” “In general, the new female specialists don’t want to do this”. This statement could not be further from the truth. I have worked in a large private maternity hospital for a significant time. The extinction of private maternity services has nothing to do with lack of male orientated “true private care,” and everything to do with socio-economic and operational factors. The fact that females have more of a natural, intrinsic understanding (and lived experience) of what pregnant and birthing women want and need is irrefutable. I dare say, the increase in private sector female obstetricians has slowed the extinction of private maternity services.

For me it’s the out of pocket costs. The increased health insurance covers the hospital stay and that’s it. We now face reduced bulk billed ultrasounds, obstetric costs, costs for tests during our stay, the paediatrician check etc. I have birthed two children through the private system and am considering going pubic for my third purely to reduce some of the costs. I’m paying $259 a fortnight for health insurance that just ensures I get a private room and some other niceties.

We have junk private health insurance- most are getting it to avoid tax and obstetrics isn’t even covered.

If one has a high risk pregnancy, one is sent to a tertiary hospital with the proper teams and equipment- lots of IVF and higher risk babies, mums with obesity , hypertension, older and diabetes-not as safe to deliver in private practice.

The demographics of those delivering has changed- no longer as young, fit or healthy and more high risk as well.

“Around the country, private maternity hospitals are closing, with enormous implications for many Australians needing care and for the health system as a whole.”

Implications not discussed in this article include the freeing up of health professionals from the private sector to contribute to our public healthcare system, which is available to all Australians at no cost at the point of service, funded by our taxes, based on need not ability to pay, and provides more cost effective care.

https://lens.monash.edu/@business-economy/2024/01/29/1386426/modernising-medicare-making-healthcare-better-for-everyone

The lead risk factor for caesarean section in Australia is private hospital care. If we want to reduce incidence of this major surgery, then reducing private hospital care may be an effective strategy. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies/contents/labour-and-birth/method-of-birth

Thank you all for a very thorough analysis of a situation I have been watching develop for 40 years.

One facet that was not highlighted was the restrictions placed on the range of obstetric and gynaecological services available in hospitals run by religious groups. These include banning of IVF, sterilizations, contraceptive services and terminations – all of which services play a part in a competently run gynaecological practice.

A sobering summation of the problem. Every doctor should read the article. The overarching theme is a systemic shift away from private healthcare due to economic, demographic, and operational challenges. Couple this with inadequate policy responses to maintain the attractiveness and viability of private healthcare. If these trends continue, the consequences could include the collapse of specialized care sectors like maternity and a more profound impact on the overall health system’s stability in Australia. This calls for a critical evaluation and potential rethinking of health policies, especially around insurance structures and healthcare funding, to prevent further decline and ensure both public and private systems can function effectively and sustainably.

In New South Wales, private maternity services are experiencing significant growth due to several factors. Post-COVID, immigration has surged, and many immigrants are securing visas based on their skills, leading to better employment and access to private health insurance. Additionally, the children of the immigrants who settled in the previous decade are now beginning to start their own families. This demographic also tends to favor private hospitals for maternity care. Furthermore, the general perception of care in public hospitals is deteriorating, resulting in an increased demand for private maternity bookings. As a result, some private maternity services are struggling to meet the heightened demand.

It would be interesting to survey consumers to determine what is deterring them from private care. I suspect out-of-pocket costs, even for the highly insured, may be the most significant factor.

Another factor not mentioned is that male obstetricians will also soon be extinct as for many years now less than 5% of trainees in O&G are male. Male obstetricians have provided the majority of true private maternity care. In general the new female specialists don’t want to do this and hence the move to group practice. No real studies have looked at patients satisfaction with this change. The college has remained absolutely silent at the lack of diversity in their intake and certainly appear uninterested in the demise or male obstetricians!

General failure of late stage capitalism I’d say.

The proportion of private births was higher when boomers and older gen X were of childbearing age. Now they’ve aged out of that life stage, those under 35 having children today are needing 2 full time incomes to scrape by. They are making a financial decision that Gold Hospital cover isn’t worth it for maternity, you don’t get to skip a wait list and the holistic input on offer from the public system via social workers, lactation consultants, pain specialists, physio, perinatal psychiatrists etc (all of which which nobody knows they need in advance) is something that no private hospital can compete with when it costs $0.

Plus the safety of delivering in a hospital with a NICU on site rather than needing NETS road transfer… I don’t blame them.

The essential problem is Medicare, not the value proposition of private health funds. In 1983, when only the indigent used public hospitals and 80% of the population had private insurance, the wait for a public hip replacement was two weeks. After 1984 with the introduction of Medicare and the consequence drop in private insurance coverage, the wait is now 2 years.