The “baby bust” must be part of Australia’s political agenda, so we can overcome this existential crisis, write Dr Clare Boothroyd, Dr Katharine Bassett and Professor Steve Robson.

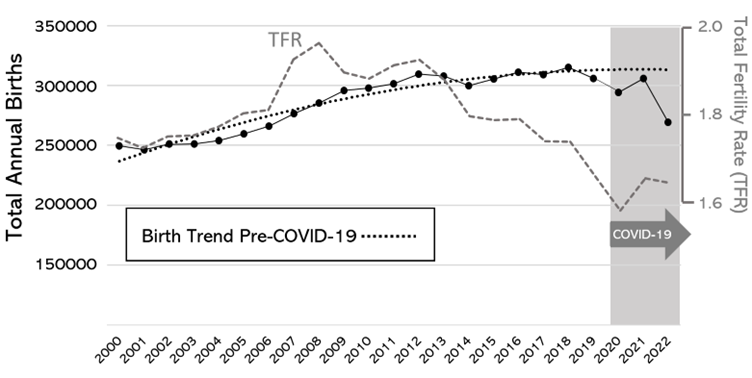

The “baby bust” is a unique and existential crisis, never before encountered in human history. In 2020, fewer than 300 000 babies were born for the first time since 2007, and the total fertility rate (TFR) estimate for the year had fallen to 1.58 babies per woman over the lifetime. This is the lowest TFR in Australia’s history, representing a fall of 56% from the peak in 1961 (when the TFR reached 3.55 babies per woman).

Although a slight rebound in the number of babies born was observed in 2021, perhaps the result of people delaying pregnancy rather than abandoning the idea altogether, the fertility situation again appeared grim with release of the latest 2022 statistics. Australia’s TFR has remained stuck below 1.7 babies per woman since before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the longest period in the nation’s history.

These cumulative results rung alarm bells, prompting former Australian federal Treasurer and architect of the “Baby Bonus” initiatives of the early 2000s, Peter Costello, to make a public call for new policy measures to increase Australia’s birth rate.

In the most recent Intergenerational report, released by the Australian Treasury in 2021, the significance of falling birth rates for Australia and its economy was noted but not addressed. The Treasury comments were predicated on concerns that, “for the first time in an intergenerational report, the population projection is being revised down”. An ageing population has a number of well recognised and interrelated effects:

- an increased need for social services;

- increased demand for health care;

- increased demand on pensions;

- a reduced labour supply and likely reduced productivity of older participants in the labour market;

- a likely reduction in unemployment in the younger members of the population.

As an example of just how high the stakes are, we need only look to Japan, where the twin threats of catastrophically low birth rates and a ballooning elderly population are rapidly coalescing. At the beginning of 2023, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishada told the world “Japan is standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society”.

The factors influencing birth rates

It is tempting to blame the “baby bust” on effects of the COVID-19 pandemic but, in reality, the pre-pandemic year 2019 also had a historical low TFR of 1.66 babies per woman. Indeed, Australia’s birth rate has been in established decline over the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

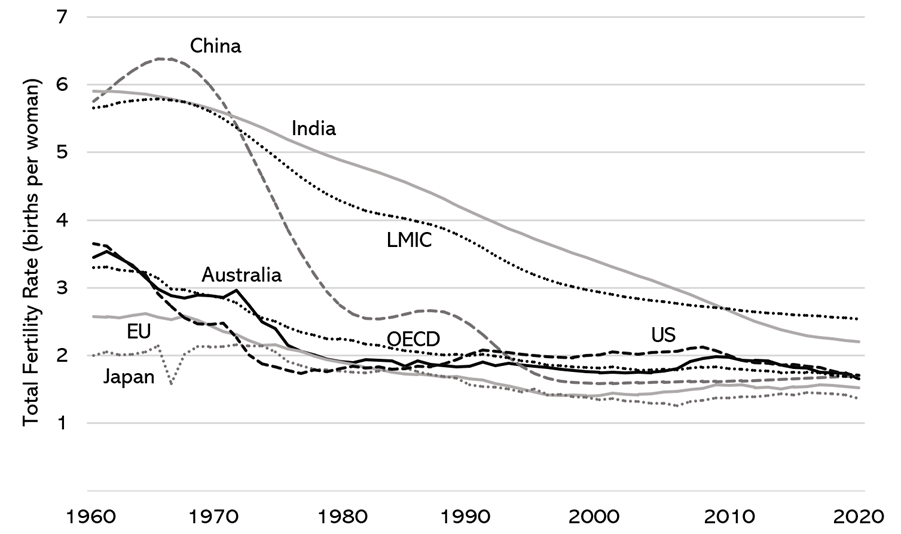

Putting this in a global context, the data for fertility rates in Australia are not unique: across the globe, birth rates and resulting TFR estimates have been in decline since the 1960s (Figure 2).

In January 2023, Treasurer, the Hon Jim Chalmers MP, announced unprecedented increases in migration rates, with as many as 300 000 new arrivals expected yearly in the short term, providing a boost in the availability of human capital. Studies suggest that migrants generally have higher TFRs. However, this has not proven to be the case in Australia.

Replacement-level fertility rates will keep a country’s population steady but will not lead to population growth if mortality rates remain unchanged and migration has no effect. Virtually all high income countries now have TFRs well below replacement level (here), with population increases dependent upon migration. Migrants generally do not arrive as newborns, so migration-based population increases distort the age distribution of a population with a skew towards older ages, with a resulting increase in the proportion of older people in the population.

Education of women is a significant component. Globally, there is a well recognised negative relationship between a woman’s level of education and the ultimate size of her family. The situation is no different in Australia, where women are investing time, effort and money in increasing their education. That is great news, but it will affect fertility. There is evidence from the United States that the greatest reduction in family size are women from disadvantaged backgrounds who receive tertiary education. Improved education usually makes life better for people, but the trade-off will be further reductions in birth rates. For this reason, increasing the flexibility of educational options will need to be an early and key policy target.

What can be done?

Convincing a large number of women and their partners to have an additional child will be no easy task. Indeed, pro-natal policies introduced in high income countries around the world have had, at best, patchy success. Australia’s own “baby bonus”, a suite of financial incentives for new parents introduced in the mid-2000s, for a short period of time had a modest effect on the birth rate and, importantly, resulted in an increase in a third child being born (here). Paid parental leave policies, which Australia has had for over decade now, have been recognised globally as having a positive effect on fertility, at least in the short term. We welcome the Australian Government’s recent announcement of women on maternity leave being paid superannuation, but more needs to be done.

The first step will be moving babies and children up the national priority list. To justify this will require taking the community along on the fertility journey. Unfortunately, most political objectives barely span the electoral cycle. If we are to increase Australia’s population through birth, then a very long term view will be required.

In addition, there needs to be general support to become a family-friendly society. This will mean starting a national conversation about the long term economic importance of having children, supporting current and prospective parents, as well as supporting family members such as grandparents who may have to help in the raising of children. This would have to become our social purpose for the next 25 years.

The most common family size in Australia is two children, yet studies report that the most commonly desired family size is actually three children. Economic incentives to increase birth rates might usefully be targeted at a third child, taking the approach that families might respond to different incentives for a first child as compared to a third or fourth child. The nature of incentives would need to be broad as well, and include support of quality, possibly work-based childcare, afterschool care centres as well as schemes that provide support to university students who wish to parent children.

For better or worse, it is important to understand and accept that the appropriate biological age for women to have children is between 20 and 35 years, and we all need to facilitate sufficient social change to allow this. One way is to encourage egg freezing by the age of 34 years (and earlier if the woman has a low number of eggs), at an age when eggs are healthy. With modern techniques, the freezing of eggs is now effective and should be considered for Medicare funding in Australia. It is quick, safe and inexpensive compared with the consequences of not preserving fertility.

Case studies from around the world demonstrate that there are few low hanging fruits left, and no easy answers. The “baby bust” is a unique and existential crisis, never before encountered in human history. To overcome it, we will need to be adaptive and insightful. Let us pool our resources to find the best solutions so we do not follow the course of some other countries. Let us make this part of our political agenda.

Dr Clare Boothroyd is a female fertility specialist and obstetrician gynaecologist in Brisbane and the President of the Asia Pacific Initiative in Reproduction.

Dr Katharine Bassett holds a PhD from the Australian National University and conducts research focused on health system reform.

Professor Steve Robson is an obstetrician gynaecologist in Canberra.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

I would ask the authors this question: is there evidence that Australians want to have more children?

The idea that people should make these sort of choices on demographic grounds seems perverse.

I am shocked that these senior professionals are of the view that the best way to combat an aging population is to create a legion of future workers. There are a plethora of other options to deal with an aging population and many reasons that a declining population is a necessity. Yes, climate change caused by overpopulation is a big issue, as is the issue of food security and access to housing. There is also the rise of AI, robotic solutions, and other technologies yet to be invented that will change the landscape of future employment, likely creating a shift to caring / human-based work and away from any jobs that can be automated. Millions of people already live in poverty. We can work smarter and more efficiently. Not to mention if families have fewer children, people remain in the workforce at a higher FTE for more of their productive working lives, pay more tax, accumulate more superannuation, and potentially will work to an older retirement age without the burden of caring for an army of grandchildren AND will be in a better position to care for their aging parents.

Further, it is disappointing that this article fails to better highlight that the burden of a larger family takes a disproportionately large toll on the woman bearing those children and often carrying the load of running the household and being out of the (full time) paid workforce. Any program aiming to encourage women to have more children needs to focus on addressing the systemic disadvantages women face as a result of having children. Having a child is an enormous responsibility requiring significant sacrifice, albeit potentially very special and joyous for many people. It is simplistic to say we need to encourage women to have more children for the good of society, rather than prioritising their own lives and wellbeing. Having a child out of obligation is not what I think we should be asking of our daughters. They are not baby making machines. This is a women’s issue – most men still want bigger families, there are several recent studies investigating this matter and consistently finding it is women (not men) who want fewer or no children.

We need to think of another way. We need to aim for a gradual reduction in global population for the sake of the future of Earth and be more clever and efficient in managing our finite resources.

I am a 30-year-old, female medical doctor, and am confident in my decision to remain child-free. The reasons are many, but the primary one being climate change. I feel existential dread about my own future on this planet, let alone that of any offspring I might bring into it. Having fewer children is the action with greatest environmental impact that an individual can make.

Also, there is the immense pressure and lifestyle challenge of completing specialty training, which I cannot imagine being possible whilst properly caring for a young child.

I understand that a declining fertility rate presents huge economic challenges, but I am actually relieved that the demands of overpopulation on our planet might be starting to slow.

Yes educated women have fewer babies. That is not a bad thing. Looking back as a boomer to millenials generation and older, I see many younger people struggling with insecure work, constant ‘contracts’ for employment instead of permanent full or part time jobs. Prospects for women with children who have to leave bad or violent relationships is dire. Men do not suffer financially anywhere near as much as women in this situation. Housing is unaffordable or just not available. Many cheap build apartments are not family suitable and nowhere near facilities that parents might want for children – childcare, schools, playground, open space and safe transport routes – driving or public or active transport. Climate change is dire as we are nearly at 1.5 degrees of warming. Forget nuclear subs and get on with rapidly cooling the planet, looking after young people with decent pay, permanent contracts, decent and affordable housing, multiple transport options, and ensure that women who flee violent relationships are able to house their children and meet their needs with dignity.

I am disappointed by this article by authors who appear to have a vested interest. Such discussions are best left to economic and environmental scientists. In my retirement (after 54 years of O&G practice) I am helping Sustainable Population Australia – an excellent organisation I can recommend to medical colleagues. The world is in unprecidented decline and the fundamental cause is Homo sapiens. For the sake of our children let us act sensibly.

It is a shame that some people think that the last thing that the planet needs is more humans. Having children is by far the most meaningful thing in most people’s lives. When people become part of a wealthy society, they end up having fewer children that are required for replacement. So, if you want fewer people on the planet, the first thing you should do is make people richer by giving people access to affordable energy. Instead, we have the sheer evil of the climate lobby making life more difficult for poor people, and sacrificing them on the alter of worshiping the planet – thankfully this as not happened in Australia.

* * * * * ** ** ** ** *** *** *** **** **** ***** **** **** *** *** *** ** ** ** ** * * * * *

This is related to the poor mental health of today’s youths. When I grew up, I did not have to contend with living on stolen land (even though I am living on stolen land). When I grew up, I did not have to put up with people saying that my mere existence was a problem for the planet. We are giving today’s youths an appalling message. No amount of (left-wing) psychologists are going to solve this problem. The last thing we need is medical practitioners say that the planet needs fewer people.

If you want to increase fertility rates you need to create an optimistic future. Educated people dont want kids because we are being flooded with information about the climate crisis. Who could possibly want children when the world is on fire, owning property (and therefore having stability) is inaccessible, and cost of living is soaring.

Australia needs to put their heads together and prioritise climate change and prove that it’s working. Protect established ecosystems from destruction, focus on renewables/nuclear energy and find ways to REVERSE climate change.

Find ways to make owning a house accessible to a young family. That way they can feel safe if the resources they own. Limit the number of investment properties moguls can own, look at smarter housing options (europe have some amazing ideas on this front that minimise foot print but also create housing clusters with close, safe access to green spaces + shops + education) and try to change this idea that property is the best way to invest and make money.

Finally Australia needs to own their own utilities to control prices. Stop selling them off to people who are only trying to make money and keep it in the hands of people invested in making things better

The last thing the planet needs is more humans, and the last thing Australia needs is a bigger tax burden.

We need to stop funding babies as an income source.

Negative population growth globally including Australia could reduce the environmental damage including climate change of over population

Missing from the above analysis is the effect of the cost of housing. Unless independently wealthy, a young couple will have no hope of saving enough to buy a house then support a large mortgage unless both are working full time. By the time that one partner has gone up the pay ladder of their chosen field to allow 1.5 FTE to be financially viable, much of the time for growth of the family has passed.