We suggest a “back to basics” approach to treating lung disease in Indigenous people in the Top End by making best use of limited resources, as shown in our recent study that used a simple chest x-ray and spirometry.

Associate Professor Ford’s mother Nancy Daiyi used to describe her health as “Ngu.ngook tjan!”.

The English translation is “I am short wind” meaning she was out of breath and finding it difficult to breathe. The Indigenous people in Australia believe that the spiritual and emotional wellbeing of body is connected to the wind – “the lungs”. To be “short wind” is to represent sickness and “good wind” means “I’m alive and well” (here). Sadly, in a high income country such as Australia, the story of “short wind” continues to be highly prevalent among Indigenous Australians with chronic lung diseases. We still have a health equity gap to bridge to the “good wind” story. Almost one in three Indigenous Australians self-report current long term respiratory disease, and hospitalisation rates for respiratory diseases are 2.4 times higher in Indigenous Australians compared with their non‑Indigenous counterparts (here).

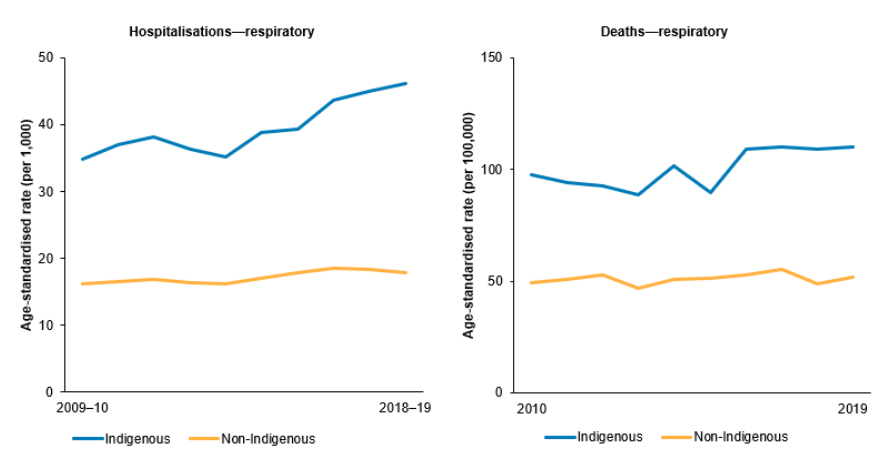

The age-standardised rate of deaths from respiratory disease, shown below in Figure 1, has changed very little over the past decade (2010–2019). Part of the systemic failure to address the disparity in respiratory health outcomes may be due to the lack of relevant and appropriate data collection and respiratory research funding allocations in the past.

Our basic understanding of lung health is lacking; that is, normative lung function values in Indigenous adults, chest radiology data, guidelines on diagnosis and disease classifications, therapeutic guidelines and interventions specific for Indigenous adults. Understandably, this gives rise to diagnostic and management challenges in day-to-day clinical practice.

Moreover, due to the lack of Indigenous-specific diagnostic and management guidelines, health practitioners inevitably adopt the established non-Indigenous management practices, which may not necessarily be appropriate. Our research from Flinders University and Charles Darwin University, Northern Territory (NT), has highlighted lung health issues among adult Indigenous patients in the Top End region of the NT of Australia in the past five years, and has demonstrated how different chronic respiratory diseases manifest in Indigenous people compared with non-Indigenous people, which is of interest for health organisations and all community stakeholders.

What does the research demonstrate?

In addition to common lung conditions such as asthma, bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), uncommon, advanced and complex concurrent lung conditions are highly prevalent in Indigenous people (here, here and here). Indigenous adults typically present with chronic respiratory disorders at a much younger age, with a marginally higher prevalence in remote compared with urban areas, and die younger (here, here and here). “Short wind” — shortness of breath — is one of the most common presenting symptoms (here).

To date, lung function (spirometry) reference norms have not been well established for Indigenous adults. This raises a fundamental question: if we do not know what is normal, how are we going to say what is abnormal? Our studies have shown that, when adopting lung function reference norms based on people of European ancestry, even apparently healthy Indigenous adults may be 20% lower and only 10–12% lie in the normal range. Indigenous adults’ lung function parameters also do not match any published ethnic populations (here and here).

Hence, there are challenges imposed in the accurate diagnosis and severity classification of lung disease in Indigenous people. Indeed, our research has demonstrated that the majority of Indigenous patients with COPD will be classified to have severe airway disease if using reference norms based on people of European ancestry (here).

Another study has shown significant differences in the manifestation of COPD in Indigenous people in comparison to non-Indigenous people (here). Hence, by applying current guidelines in the management of patients with COPD, many may be misclassified with the severity of lung disease, which could give way for potentially inappropriate treatment interventions, more specifically in the use of inhaled directed airway therapy.

Studies from the Top End have shown the concurrent presence of COPD and bronchiectasis are highly prevalent in Indigenous people (here and here). Although both conditions share similar clinical features, the management is different, especially when considering inhaled corticosteroids. Inhaled corticosteroids are recommended to be used with caution in patients with bronchiectasis. A study from the Top End has shown marked decline in lung function parameters among a proportion of patients using inhaled corticosteroids with bronchiectasis (here and here).

Although the prevalence of asthma among Indigenous Australians is portrayed to be highest in the world, much higher than their non-Indigenous counterparts, studies exploring the prevalence may have had methodological flaws by utilising patients’ recall of a past asthma diagnosis.

However, an NT study has illustrated that patients’ knowledge on their lung condition is extremely poor (here). Our study from the Top End has shown when using objective measures of accurate asthma diagnosis, the rates of asthma are not any different in Indigenous people compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts (here).

Until recently, there has been an unprecedented gap in our knowledge in relation to chest radiology data among Indigenous adults. Recent studies have demonstrated a high burden of respiratory conditions, with multiple advanced and complex chest imaging findings, including the presence of cystic lung disease and mediastinal lymph node disease (here, here, here and here). Furthermore, the use of common recreational substances can have catastrophic effects in this setting, as recently described in a case series of using cannabis via “bucket bong” (the “bucket bong” lung) (here).

Another recent study from the Top End has demonstrated for the first time that lung nodules are an extremely common chest radiology finding, yet the majority are benign (here). Data on lung nodules and malignancy are limited in Indigenous populations. To add to the complexity, remotely residing Indigenous people often have severe obstructive sleep apnoea, and acceptance of modern treatment intervention devices such as continuous positive airway therapy (CPAP) is challenging (here and here).

Sadly, literature addressing pleural effusion among Indigenous patients is almost non-existent other than a single study from the NT demonstrating one of the most common causes for pleural effusion in this population is secondary to chronic renal disease, which is also highly prevalent (here).

The future

Rates of chronic lung disease disparity in health outcomes, lack of equity and the failure of the closing the gap initiatives in the ongoing morbidity and mortality among Indigenous adults are likely to stay the same for the foreseeable future until and unless drastic actions are undertaken. The rhetoric now is how and where to from here in the quest to close the lung health gap?

It is critical that health practitioners are aware of the differing demographic and clinical manifestations of chronic lung disease in Indigenous people compared with non-Indigenous people. We argue that further research should focus on gathering clinical data, normative spirometry reference values and radiology data. Indigenous-specific guidelines for appropriate diagnosis, classification and management of chronic airway disease are paramount.

Indigenous-specific lung cancer screening pathways; robust smoking cessation programs, including ill effects of cannabis use; provision of regular physiotherapy services for airway clearance; and education to empower patients to take responsibility for their health are required. This will not be achievable unless there is a shift in relevant health organisations, stakeholders and, more importantly, research funding bodies to engage and support Indigenous health workers and practitioners in regional and rural communities for clinician-led research to address realistic needs.

Until then, we suggest a “back to basics” approach by making the best use of limited resources to aid in the appropriate management of respiratory disorders in remote Indigenous communities. As demonstrated in a recent study, utilising simple chest x-ray and spirometry has fair sensitivity and specificity in the accurate diagnosis of chronic airway disease (here).

Although we have demonstrated several aspects of the respiratory health burden in Indigenous people, including issues relating to pulmonary function testing and appearances on chest computed tomography (CT) and endpoint datasets, much more work remains to be done. The Australian Government-approved Lung Cancer Screening Program and co-design work, with a collaborate yarning methodology, working with National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), is in progress, with a fully funded low dose chest CT Lung Cancer Screening Program set to commence in 2025 (here, here and here).

We have to wait and see if this work may shed more light on respiratory health burden in the wider community of Indigenous Australians to reduce the disparity in respiratory health.

Associate Professor Subash S Heraganahally is the Head of the Department of Respiratory and Sleep at the Royal Darwin Hospital, Director of Darwin Respiratory and Sleep Health at Darwin private hospital and an Associate Professor in the College of Medicine and Public Health at Flinders University.

Dr Timothy Howarth is a Researcher for Darwin Respiratory and Sleep Health at Darwin private hospital and a Post-Doctoral researcher in the Sleep Technology and Analytics Research group at the University of Eastern Finland.

Associate Professor Linda Ford is a Mak Mak Marranunggu woman from the Northern Territory, and a Senior Research Fellow in the Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University.

Dr Lisa Sorger is the Chief Medical Officer for Integral Diagnostics and Consultant Radiologist at Apex Radiology Western Australia.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert