Before we reinvest blindly in Medicare or hospital care, we really need to map out the service landscape of community mental health care, writes Dr Sebastian Rosenberg.

Readers who follow the fortunes of Australian mental health reform continue to endure the vicissitudes of political attention and recognition. The (then) Council of Australian Governments spent more than $5 billion over five years starting in 2006. The then-Treasurer, the Hon Wayne Swan MP, made mental health the “centrepiece” of the 2011 federal budget. We’ve had roadmaps. In 2018, the then-Treasurer, the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP, referred the issue of mental health reform to the Productivity Commission, which delivered its report in 2020. We’ve had visions and we’ve had pillars.

A roller coaster of emotions

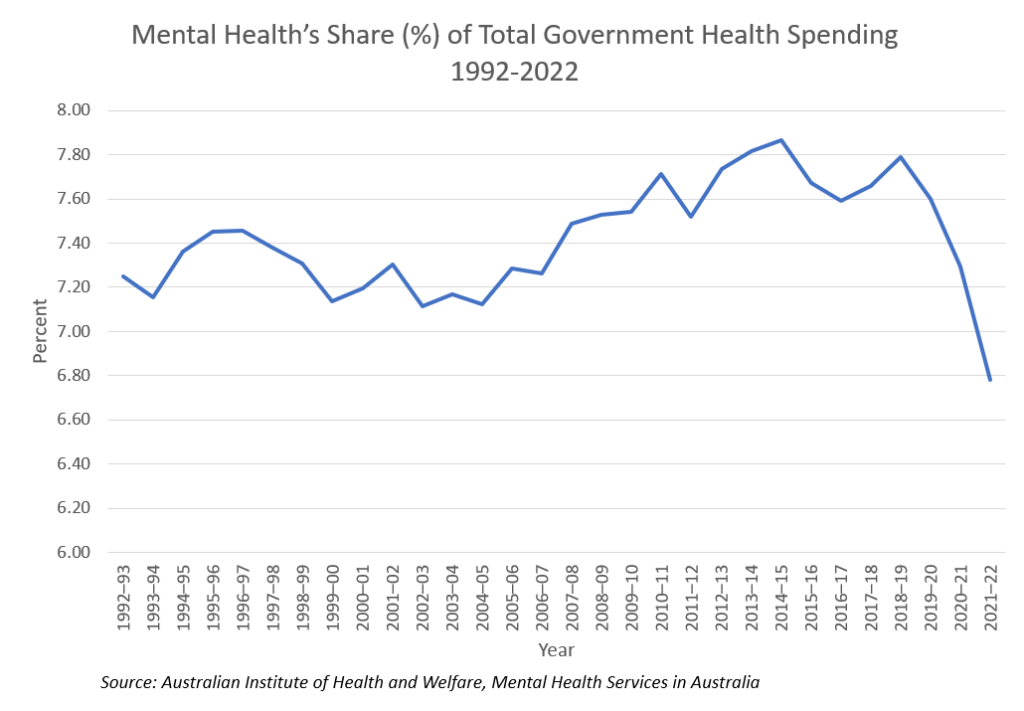

But in the end, the disappointing slippery dip of Australia’s mental health reform journey is revealed in the graph below, which shows mental health’s share of the total government spending on health care at 6.78%, the lowest it has been since 1992, the year Australia’s National Mental Health Strategy began.

At the same time, there is new evidence indicating that mental health now represents some 15% of the total burden of disease. Mental health conditions and substance use disorders are now the second leading disease group causing total burden in 2023 (15%) and the leading disease group causing non-fatal burden (26%). The gap between the funding and the burden may not explain everything about today’s crisis in mental health care but it remains a key challenge and certainly explains something.

All the activity in mental health, the myriad policies and plans, rather calls to mind a Monty Python sketch where all of a sudden, as if all at once, “nothing happened”.

Currently, my fellow collegues with an interest in this area are looking forward to seeing the findings of the Mental Health Reform Advisory Committee, set up by the Minister for Health and Aged Care, the Hon Mark Butler MP. However, their remit is rather limited to responding to the recent evaluation of the misfiring Better Access Program, rather than broader mental health reform challenges.

In this context, advocates for reform could become justifiably despondent.

Opportunities for change

However, there are several opportunities in the current policy environment worth noting. Both concern federal and state relations. And both concern the key missing element in Australian mental health care: community mental health.

At the time of deinstitutionalisation of mental health, the apparent aim of mental health reform was to enable people with mental illness, wherever possible, to live with dignity, in the community, in their own homes. There were noble intentions about employment, education and social inclusion. In the intervening years, neither federal nor state government has fully taken responsibility for community mental health. Mobile, community mental health teams have withered, and investment in psychosocial services never occurred. As a consequence, it has been said that institutions were in fact replaced by two other institutions, the acute psychiatric wards of our public hospitals, and jail.

So, a first opportunity arises in relation to calls to reconsider what qualifies as out-of-hospital care under the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA). Without wishing to bore you (enthusiasts can read about the relevant financial “glide paths” here), the NHRA is the main agreement under which the federal government funds the states to run hospitals. In an acknowledgement of the overwhelming over-reliance on hospital-based mental health care, there is now some interest in infusing this agreement with a greater range of out-of-hospital service alternatives. For the first time in many years, key financial instruments of government may be the catalyst for real reform. Speaking practically, here in the Australian Capital Territory, the government is facing the prospect of investing in a new 80-bed inpatient facility in our northside hospital. I am sure they would welcome any intelligent opportunity to avoid embedding these costs into the Territory’s forward estimates. Well known services like “hospital in the home” actually began in mental health. The sector needs to work quickly to build some consensus around what out-of-hospital mental health services look like and what are the preferred models.

A second current opportunity in mental health arises from the recent review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). As at June 2023, the NDIS reported just over 62 000 participants with psychosocial disability receiving average support packages of $71 600 each. Total psychosocial support payments under the NDIS increased sharply that year to $4.25 billion, up from $3.11 billion the previous year. By way of comparison, and bearing in mind NDIS users can of course access hospital services, states and territories reported (in 2021–22) spending just under $7.4 billion on 457 000 mental health clients.

The NDIS has to date been unable to report that this expenditure has resulted in long term positive outcomes for NDIS clients in areas such as employment. There is some concern about the merit of this spending. The lack of transparency about what clients buy with their packages inhibits accountability and systemic quality improvement.

There is also real concern about the large group of nearly 300 000 people with psychosocial disability stranded without access to NDIS support. For this reason, governments are interested in exploring what might qualify as “foundational supports” for people requiring psychosocial care. As with the NHRA, there is some potential for the federal government to provide financial assistance to establish a new range of psychosocial support services for people not on the NDIS lifeboat.

At the same time as these broader reform opportunities are emerging, general practitioners are clearly keen to focus attention towards perceived critical funding shortfalls affecting their role in primary mental health care.

Community mental health is the key

The critical message from all of this is disorganisation. Before we reinvest blindly in Medicare or hospital care, we really need to map out the service landscape of community mental health care. We need to decide, whether it’s funded as a foundational support or as out-of-hospital care or whatever, what are those key clinical and psychosocial services people need to help them recover and stay well in the community and how we can provide these equitably. This is particularly important for people with more severe or complex needs if we are to obviate the requirement for expensive, often traumatic hospital admission. Although most of the component elements of an organised, effective community mental health service response are known, the overall service landscape outside of Medicare or the hospital remains largely undrawn and plagued by ambiguous governance.

We can address problems in the NDIS. We can reduce our overreliance on hospital-based mental health care. The opportunities to change key federal and state financial relationships in disability and health mean it could finally be time for community mental health care to receive the attention it has for too long been denied.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg is an Associate Professor at the Health Research Institute at the University of Canberra and a Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre at University of Sydney.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

The NDIA/NDIS is allied-health primitive. Labor very clearly do not like community/private/psychologists. You can get access to the NDIA with a psychologist’s opinion but you most certainly won’t maintain your review funding after that first year – you’ll need exclusively either an OT or a physio for that. Good luck in managing the distress and risk – and also the ongoing nature of patient care. Nice one Labor. So let’s recap: If you destroy Medicare and the NDIS/NDIA is allied-health exclusive, what do you reasonably expect?

Does Australia have an “overwhelming over-reliance on hospital-based mental health care”?

Australia tends to have relatively few inpatient mental health beds, and works them hard with short stay admissions, based on policy trends from the USA.

Australia closed most specialist mental hospitals during deinstitutionalization, and reduced its mental health beds down to approximately 40 beds per 100 000 people, mainly in general hospitals, which is substantially below the international high-income-country median of about 65 beds per 100 000 people. Many European countries have more mental health beds.

Too few beds and long waits for patients in emergency departments before mental health admissions is an Australian problem.

This is not to suggest that Australia has got the community mental health care equation right either. This is another part of the Australian problem.

Thanks for this article. To solve some of these problems we will need to walk and chew gum. The SA Unmet Needs study has shown, and the soon to be finished national study will soon show the scale of unmet need for psychosocial support. The SA study showed 75% of people with severe mental illness and a need for psychosocial support have their needs unmet. That is 19000 people in SA who can’t access this important part of mental health care. Fixing that problem will cost a relatively modest $125m pa (in SA) and will go a long way to balancing our mental health system. If integrated well, people actually get better and it will take pressure off crisis and acute hospital settings as well as primary care. As Sebastian has pointed out – now is as good a time as any to reinvigorate our efforts to achieve mental health reform to better support Australians to move from being unwell to leading great lives.

Foundational supports being proposed look like they will meet only a fraction of peoples needs. With the small budgets being proposed it looks like only a one hour visit from a peer worker a fortnight. So I am surprised that this is being seen as such a great solution. I am also surprised to not see more criticism of the early intervention pathway, with the limited menu of options being proposed and a stressful 3 year time frame.

It is disappointing to see the hospital versus community argument peddled out again, often by those who aren’t actually involved in the delivery of services.

A truly responsive system has to have a range of options from low intensity to high intensity services in both the community and hospital settings across the lifespan.

A very good piece which departs from the usual academic bleating of “more money” and “GP’s should” and actually offers solutions.

As is usually the case, the issue is not lack of funds but wasteful spending of funds.

Better allocation of money and accountability for spending would make a big difference, Sadly this is never the outcome with government.

The importance of community mental health care, and true understanding, not just lip service from employers, cannot be underestimated.

Thanks Sebastian. I am sick and tired of all of us having to repeat what is so obvious. We as a community of professionals must also resist the government’s propensity to call a Royal Commission into everything – this is the sure shot way of passing the buck. A case in point – the Victorian RC into the MHS!

The government of the day keeps repeating that they have invested $6B everyday, but on the coal face, as a Director of Psychiatry in a major metropolitan hospital, I haven’t seen a cent since 2021 -22!

I concede that a once in a generation covid pandemic did intervene and a lot of money had to be put into it.

But please, the politicians need to stop saying they have done their bit to create the world’s best mental health service, when really there is no money. Like the old adage goes, if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys.