In part two of this series on health system reform, Associate Professors Cate Kelly and Doug Johnson from the Department of Medicine at the University of Melbourne discuss the need for health care reform that is workforce-centred.

After many years of working in the Australian health care system, we believe more can be done to implement integrated, sustainable health care reform.

In our previous article, we discussed the current challenges to our health system and ways that reform could be person-centred, with a particular focus on addressing the root causes of care fragmentation that create clinical risk, waste resources, and are source of frustration to system users.

Many of these issues also create challenges for our workforce and, in this article, we propose a second critical approach: workforce-centred reform, where the system vision and strategy are designed in a way that recognises, values, supports and optimally makes use of our greatest asset — our people.

The article recommends some ways in which this could be undertaken. This list is incomplete — it is designed as a start point for broad discussion about how we might systematically embed a workforce-centred approach into our health reform.

What would a truly workforce-centred health system look like?

Our workforce is the most critical resource of the health care sector as well as a substantial cost, accounting for around 70% of total hospital expenditures (examples here and here).

In addition, it is likely there will be an increasing mismatch between workforce availability and workforce needs over coming years without substantial reform (here and here). As stated by the World Health Organization:

“Health systems can only function with health workers … the highest attainable standard of health is dependent on their availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality.”

Health system reform must therefore reflect the needs of our workforce now and into the future. This aligns with the recommendation from the WHO, which states:

“Health and care workers need safe, healthy, supportive, and dignified conditions of work. [Countries should consider ways to] protect health and care workers and safeguard their rights, and to promote and ensure decent work, free from racial and all other forms of discrimination and a safe and enabling practice environment.”

There is broad acknowledgement that health workforce reform is essential for a sustainable system (here and here), but experience has shown that successfully translating strategy into meaningful action has a range of challenges, including a complex regulatory and funding environment, significant lag time in producing independent practitioners, managing wide-ranging stakeholder viewpoints, and appetites for change and managing multidisciplinary reform across states and territories.

The National Medical Workforce Strategy proposes responses to some of the system challenges. With the current appetite for major reform, it would be timely to translate strategy into action and tackle some of the “wicked” challenges in health workforce. This requires consensus and commitment to a strategy that is integrated across all disciplines and health care sectors and in which all stakeholders focus on person-centred and workforce-centred reform.

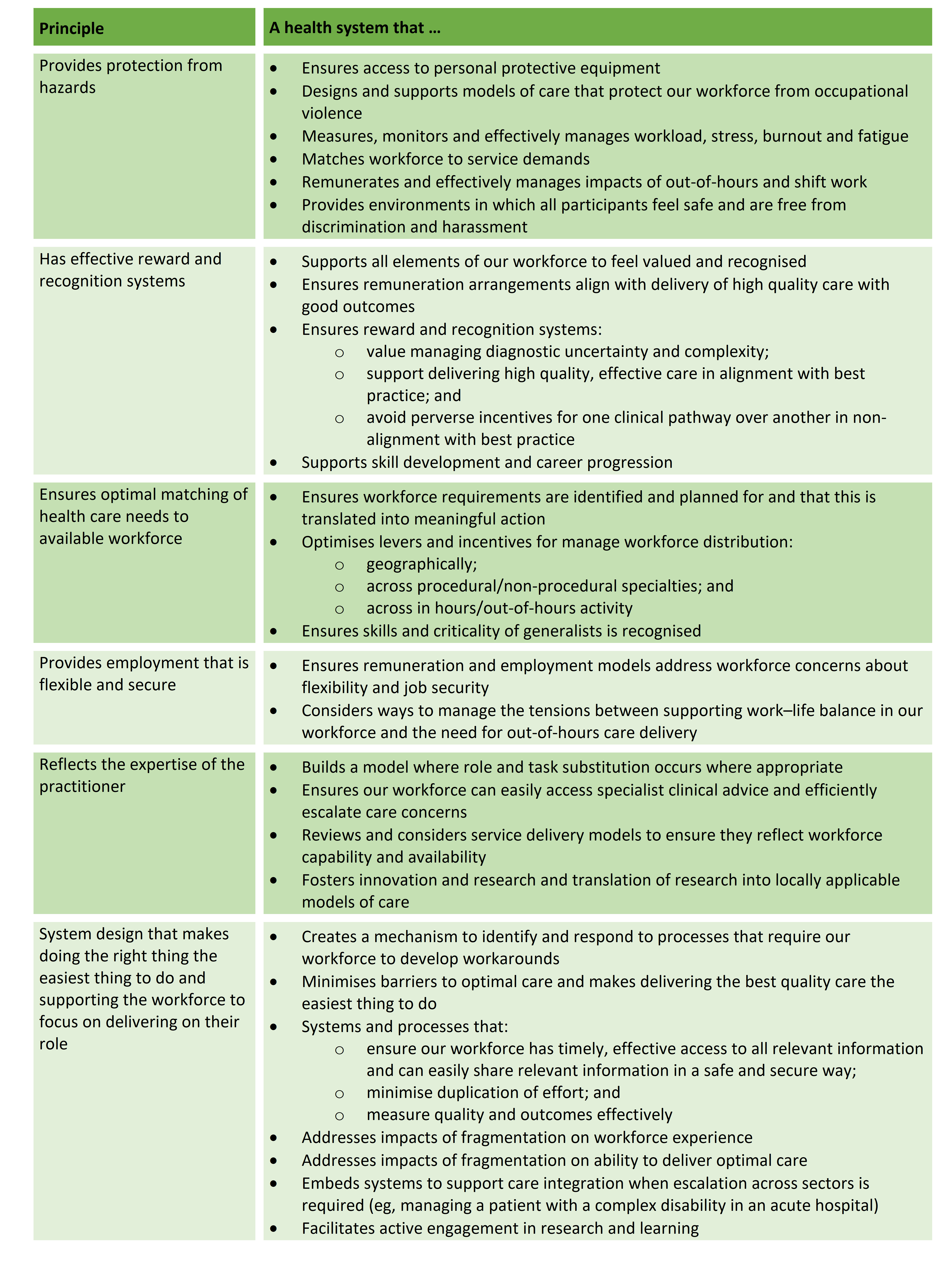

Some examples of a system that is workforce-centred are proposed in the Table below. This is a starting point for discussion rather than a complete list and broad consultation would be required to prioritise and refine key elements.

Designing a workforce-centred health system: what might that look like?

Where to from here?

With the current interest and appetite for system reform, it would be timely to revisit our overarching health system vision and strategy to test these for being both person-centred and workforce-centred.

The recommendations above and in the previous article provide a starting point for discussion, but meaningful workforce and community engagement is required. Many of the challenges currently for both people using the health system and the health workforce reflect fragmentation and lack of integration.

Some of the questions for us to consider as we test the above recommendations against our current vision and strategy include:

- How do we understand and manage the system interdependencies and how do we holistically manage risk at the interface between sectors?

- How well do our remuneration models reflect outcome-focused care, system integration and changing models of care?

- What are our societal expectations of progression of care (ie, how quickly will my care occur and what can we sustainably deliver)? Is there consensus regarding this and do our models of care and remuneration models reflect these expectations?

- What is our commitment to support and develop our greatest asset — our workforce? How will we achieve this?

- What is our agreed standard for appropriate care of our vulnerable populations? Do our systems, processes and workforce distribution adequately reflect these?

- How do we detect potentially lower value care and manage inappropriate variation in care, particularly as evidence evolves and develops? What are our system-wide approaches to ensuring we minimise inappropriate or low value care?

Australia is extremely fortunate to have the health system we do, but there are significant opportunities to further improve it — to make it less fragmented and more efficient, effective and sustainable.

There is a unique opportunity in the current environment to tackle some of the complex, thorny, “wicked” challenges facing our health care system, and approaching these through the lens of person-centred and workforce-centred reform will support all users of our health sector as well as our critical assets — our people.

Associate Professor Cate Kelly is a Board Director, Health Care Consultant and an Honorary Clinical Associate Professor at the Department of Medicine at The University of Melbourne.

Associate Professor Douglas Johnson is the Director of General Medicine, Medical Services at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and an infectious diseases and general medical physician.

Read Part One in this series on health system reform.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert