Australia’s focus on reducing domestic greenhouse gas emissions while seemingly ignoring responsibility for exported emissions is morally wrong.

The 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR) positions climate change and the net zero transformation as one of five major forces shaping Australia’s future economic prosperity — alongside population ageing, technological and digital transformation, rising demand for care and support services, and geopolitical risk and fragmentation.

It’s clear that tackling climate change is also a major health imperative, given the significant direct and indirect health impacts already being observed across the globe, including from extreme weather events. These extreme events also have an impact on power, transport and communication systems, which in turn affect our ability to meet an increased demand for health services – just at the time when people need health services the most.

Here at home, we’ve recently experienced unprecedented bushfires and smoke pollution, record levels of rainfall and floods (and an outbreak of mosquito-borne Japanese encephalitis) (here, here and here). This has resulted in fatalities, exacerbations of chronic diseases, and the mental health impacts from loss of loved ones, livelihoods and expectations of a safe and stable future (here and here). This latter issue extends beyond those directly affected by extreme events; indeed, climate-anxiety is an increasing concern among young Australians.

Overseas, health impacts of climate change are even more significant, particularly in lower income countries that struggle to supply the basic health infrastructure (here, here and here). We can take our health infrastructure for granted in Australia, such as safe drinking water and sanitation services. Australia’s new international development policy pledges to increase our climate investments and better address climate risks in our region.

But what is missing from the Australian public policy debate about climate change and its impact on health are the health impacts that arise overseas as a result of our fossil fuel exports – coal and, increasingly, gas.

Globally, more than 4 million deaths were attributable to outdoor fine particle (PM2.5) air pollution in 2019 (here). It is estimated 1.05 million deaths could be avoided by eliminating PM2.5 from the burning of coal (14.1%), oil and natural gas (13.2%).

Although there has been some improvement in annual exposure to outdoor PM2.5 in South-East Asia, East Asia and Oceania, statistics show that South Asia consistently endures exposures substantially higher than other regions (here).

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of both coal and liquified natural gas, producing 7.8% of the world’s coal and 3.7% of the world’s gas. The export revenue from thermal coal and liquified natural gas is forecast to be $38 billion and $68 billion respectively in 2023–24, lower than it has been in previous years.

This means our continued reliance on fossil fuel export revenue is shortening the lives of tens of thousands of people in other countries every year from the PM2.5 emissions arising from the combustion of our fossil fuel exports. And that is without considering the health impacts of other products of fossil fuel combustion, such as sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, and the health impacts of climate change.

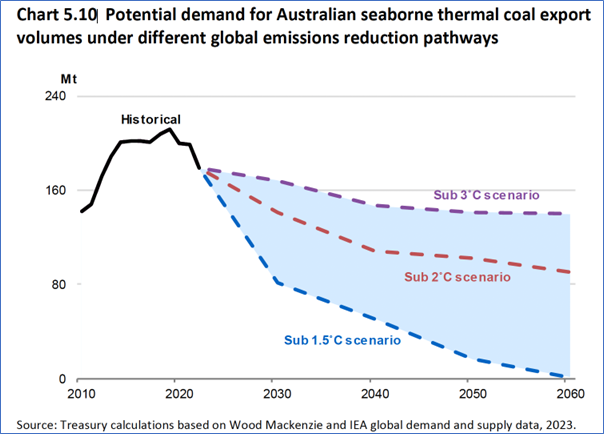

Returning to the 2023 IGR, we see that Australian fossil fuel exports are expected to decline in the future, but the speed and scale of this decline depends on the effectiveness of global efforts to tackle climate change.

If the world acts to keep global heating below 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels, demand for Australian thermal coal is expected to be less than 1% of current levels by 2063, and about 50% lower if action limits it to 2℃ (see the IGR Chart 5.10, below).

For gas, the decline in demand will depend on whether countries use liquified natural gas for electricity generation as part of their transition.

To ensure Australia remains a high income country in this changing global energy market context, Australia urgently needs a plan to reduce reliance on revenue from these fossil fuel exports which will inevitably decline in future.

Reducing our reliance on this source of foreign revenue now will have the additional benefit of immediately reducing health harms caused by air pollution from the burning of Australian fossil fuels in other countries.

In 2022, Australia updated its Paris Agreement Nationally Determined Contribution to reduce emissions by 43% from 2005 levels by 2030 and reaffirmed its commitment to net zero by 2050. But Australia’s focus on reducing domestic greenhouse gas emissions while seemingly ignoring responsibility for exported emissions is morally wrong.

To be a globally responsible nation, we should rapidly transition from being part of the problem with climate change and air pollution to being part of the solution.

And that includes rapid diversification of our sources of foreign revenue, if Australia is to be a credible host for COP31 in 2026.

Australia has large reserves of minerals such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements which are key to clean energy technologies, and abundant sources of renewable energy and open spaces, meaning it is well placed to develop a renewable export industry and power transition to a more sustainable world within and beyond Australia’s borders.

Getting on this positive path will help to address rising eco-anxiety among young Australians.

It will also ensure economic prosperity for future generations of Australians of all ages, noting that the transition must be socially just to avoid entrenching existing social inequities or creating new ones.

We are morally obliged to get this right for current and future generations, both here in Australia and overseas.

Angie Bone FAFPHM is a public health physician and Associate Professor of Practice in Planetary Health at Monash Sustainable Development Institute in Melbourne. She is a member of Doctors for the Environment Australia and the Public Health Association of Australia.

John Thwaites AM is a Professorial Fellow at Monash University, and Chair of the Monash Sustainable Development Institute and Climateworks Centre.

Tony Capon FAFPHM directs the Monash Sustainable Development Institute. He is a public health physician, a member of the MJA Editorial Advisory Group, and a member of the Expert Advisory Committee for the Climate and Health Alliance.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

We need to dramatically reduce our dependency on oil and coal for energy, not because of some supposed climate crisis but because they are finite resources and we need petrochemicals for lots of things such as lubricants, plastics, pharmaceuticals etc. No alternative source of power can provide these.

That said, depriving our own country of the economic and therefore, standard of living, advantages that coal based electricity offers whilst exporting the same all over the world for larger, “less responsible” nations to use as they like is just stupid. It’s also hypocritical and even immoral as some would like to put it but first and foremost, it’s plain stupid.

This ridiculous plan of employing solar panels and windmills here whilst sending coal overseas will send us plummeting to third world status whilst doing nothing to reduce emissions. We must use the cheap coal power here, enabling us to build a strong enough economy to be able to invest in nuclear power and wean ourselves off the coal as we transition to nuclear in future. Hopefully, the cheaper and more reliable power at that stage will help us transition to a stronger economy that doesn’t rely on exporting raw materials to survive.

Poorer countries do need the opportunity to develop but are in many cases also at greater threat from impacts of climate change than rich countries like Australia. Meaningful development involves poorer countries developing new energy economies, not being harnessed to flagging fossil fuel economies.

Furthermore, the large majority of our coal and gas goes to rich or richer countries, such as Japan, Korea and China.

We are digging and pumping increasingly more fossil fuels for our short-term and short-sighted benefit and not to save the world’s poor.

Our current approach to fossil fuel exports is indeed immoral and our self-justification is that of the drug dealer.

It is disappointing when too many of the responses to climate change seem to proceed from naive virtue rather than practical reality.

The leaps in reduction of world poverty relate directly to the ready availability of cheap energy from fossil fuels over the last 150 years.

Andrew Nielsen (Oct 16, 9.34am) may be correct that it is immoral to deprive people of cheap energy: it is certainly naive to imagine that people will accept with equanimity being deprived of the standard of living to which they have recently been lifted and grown accustomed. The frank misanthropy of some medicos to the potential plight of existing populations seems out of character.

The notion that we can simply stop using fossil fuels without a wholesale de-industrialization of the entire world is fanciful – renewables simply don’t cut it, whatever their boosters assert – and widespread civil unrest is a real risk. No democratic government could survive it, as evidenced by the baby steps recently taken in the UK to walk back the 2030 targets to 2035 on ICE vehicles, for example. Even the UK Climate Change Committee – advocates for net zero – admit that the UK will still derive 50% of its energy needs from fossil fuels in 2050.

The war in Ukraine has revealed that in fact energy security is at present a greater priority than net zero targets. That means making use of and developing our own resources as well as being a dependable supplier for others.

We should welcome efforts to transition away from fossil fuels, but such efforts need to be grounded in what is actually achievable rather than simply magical thinking ourselves to some arbitrary target.

The planet will cope as it has done for the last 4 billion years; and humans will adapt in as many ways as they can.

Thanks for this alarming reminder of the the implications of climate change, and how we as Australians are contributing to a frighening future scenario.

However I have to pull you up on the claim that Australians have safe drinking water. Some Aboriginal communities in remote regions of Queensland, WA and NT do not have safe water on tap, reflecting on-going impacts of colonisation.

Bone, Thwaites and Capon give Australia a very thought provoking reality check. It’s in no-one’s interest to keep pushing polluting fossil fuels to the rest of the world. We can’t keep looking away and pretending we can’t see the damage Australian fossil fuels are doing both here and overseas. We need to help our export partners move away from fossil fuels not try to keep them dependent on it – for all of our health as well as that of their economies and ours.

We are already well above 1.5 deg C compared to pre-industrial limes (Australia was 1.47 deg C above that baseline reported at the Glasgow COP 2 years ago).

Just how are we to reduce our coal and gas exports, given the revenue they generate, and the implacably destructive behaviour of the fossil fuel companies, many or most of whom now breaching definitions of ecocide?

Do we really want Australia’s precious but parlous and ancient ecosystem further destroyed by the mining of lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements? To state that we are “well placed to develop a renewable export industry and power transition to a more sustainable world” is to totally ignore the urgent need to rapidly and profoundly reduce per-capita energy consumption, particularly in the Global North, where the profligate Australia lies.

I think cutting off poor people’s access to cheap energy is immoral. Better than they burn coal than animal dung. Animal dung is quite the champion for indoor air pollution. Environmentalists’ only solution is to yell no. When it comes to policies for cheap, renewable energy, there is just a deafening silence. The Greens even say “no” to wind farms and nuclear power.

Eco-anxiety? That’s a problem? Well, stop people telling primary schools that there is going to be an imminent disaster when the child can’t do anything to prevent it and is not yet capable of abstract thought. I grew up with the privilege of not being told that my carbon footprint made me a liability for the planet and without being told that I am living on stolen land. Worsening youth mental health, anyone?

And Australia not exporting carbon would not help anyone’s anxiety. People would still be saying that if nothing changes in the next 10 years there will be a catastrophe. Same as people have been saying for decades.