The Strengthening Medicare Report lays the foundation to redesign mental health care around a generalist approach, fundamentally helping reverse Australians’ poor mental health outcomes.

Bea*, a 28-year-old, is struggling with her mental health, but she is not seeing her GP for mental health support, she has other health priorities she needs to address. Having already used her five physiotherapy sessions provided in her Chronic Disease Management Plan, Bea tells her GP that her ongoing pain, the result of a serious accident years ago, has gotten so bad she has been unable to work and now she is struggling to pay her rent. Even though Bea’s pain and financial difficulties are causing her a high level of psychological distress, she is not seeking mental health treatment. Bea is one of the thousands of Australians struggling with their health that seek help from a GP every day.

The 2020–21 Australian National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) found that of the one in five Australians who had experienced a mental health disorder during the preceding year, less than half had consulted a health care professional about mental health. Of the 53% who had not consulted with a health care professional, 89% indicated that they didn’t want to receive mental health information, 80% didn’t want to access mental health counselling, and 95% didn’t want medication.

Bea is one of these people, and like the many other Australians living with a complex health condition, she is getting lost in a health care system that is not arranged to meet her complex care needs. This is the reality of health care in Australia that too often only GPs and other frontline health workers see, and this is why they, and the people they care for every day, need a new approach.

To tackle Australia’s mental health crisis we need to put the mind and body back together and we need to reform primary care in a way that allows it to draw upon the strengths of all parts of the health care system, including strong community-based approaches. It is time for the disciplines and silos to unite in the best interests of Bea and people like her.

Reforms such as Better Access to Medicare-funded mental health care and building additional in-patient treatment capacity are only part of the solution. Since the 1990s, Australia has taken major steps in making access to mental health care specialists easier, beginning with the National Mental Health Plan in 1992. Then in 2001, the federal government launched the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care initiative, which allowed local divisions of general practice to purchase non-pharmacological services from mental health specialists; and in 2006, Better Outcomes was replaced by the Better Access initiative, which enabled people to access Medicare rebates for specific mental health services.

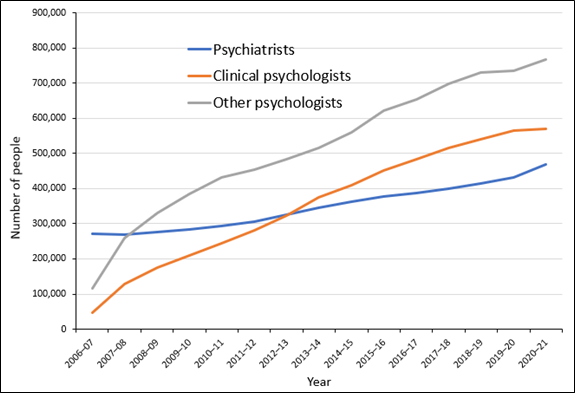

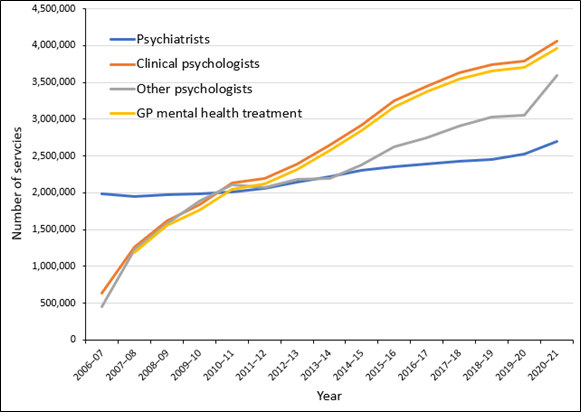

These initiatives have provided Australians with much needed access to mental health specialists via a GP for the past two decades and we have taken up this support in large numbers. Since the introduction of Better Access in 2006, the number of Australians accessing mental health specialists care has been increasing by an average of 91 000 people each year (Figure 1) and the number of Medicare-subsidised mental health services accessed has been increasing by an average of 680 000 services each year (Figure 2).

Nevertheless, the prevalence of mental health disorders in Australia has remained stubbornly high with the 1997, 2007, and 2020–21 waves of the NSMHW reporting that the number of Australians who had experienced a mental health disorder in the previous 12-months were 18%, 20% and 21% respectively.

General practice is often the first place someone with mental health needs presents, and although mental health care provision is an important and rewarding aspect of being a generalist medical practitioner, getting people the right care first time is very challenging. As a GP, I have sat with people like Bea as they talked about the problems they have been experiencing and together we have tried to find solutions.

My experience is that finding those solutions can be extremely hard work, and very time consuming for both the GP and the patient. The Australian primary care system is not well supported to meet the complex care requirements of the community it serves and, consequently, too often I have seen people like Bea spend their time marking time or going in circles.

My time as a practitioner has coincided with access to safer antidepressants and Better Outcomes/Better Access Medicare-subsidised psychological care, both essential components of care, but my research has demonstrated that meeting someone’s mental health needs requires a more holistic approach. I have spent more than 20 years researching evidence-based ways to strengthen the general practice response to mental health.

Starting with the diamond cohort study, where we tracked the experiences of primary care attendees living with depressive symptoms over ten years, we have built the evidence base for a model of care that supports the whole person taking into account their physical, mental, relationship and social needs. The research has also shown that we need simple reliable ways to identify and guide people like Bea as early as possible and we need better-established pathways to get her the right care and support the first time.

In two gold standard randomised controlled studies, Target-D and Link-me, conducted by my team at the University of Melbourne, we tested a model of care to assist GPs meet their patients’ metal health needs. Beginning with Target-D, we used a brief set of questions that could be easily embedded into routine care to predict depressive symptom severity at three months.

In the Target-D trial, based on their responses, participants were triaged to one of three “level of need” groups (mild, moderate and severe) and were provided with treatment options tailored to that level of need. Further, as participants triaged into the severe group were identified as having complex needs, the Target-D model includes nurse supported collaborative care. That is, a primary care nurse who assists to develop a personalised depression management plan in partnership with the participant and the GP and acts as a care navigator to ensure the person gets access to the support they need.

In Link-me, the Target-D model of care was extended to include anxiety and other mental health conditions, and the care navigator role was undertaken by nurses and a wide range of allied health professionals. In the Link-me trial, participants who received care navigation support as part of a holistic GP mental health treatment plan, including assisted access to specialist mental health care, showed consistent improvement in both their mental and physical health and wellbeing.

Bea was one of these trial participants. Working with her care navigator, she was able to access more physiotherapy for her chronic pain, a psychologist for mental health challenges, and even a financial counsellor to help her manage the financial difficulties that were exacerbating her symptoms. Promisingly, at the conclusion of the trial, Bea didn’t just see improvements in her health and wellbeing, she was progressing towards her long term goal of returning to work.

The Strengthening Medicare Report lays the foundation to build upon research such as Target-D and Link-me, and embed holistic, patient-centred models of care into routine primary care. Importantly, if we redesign care in this way, centred around the generalist approach and putting the mind and body back together, we stand a real chance to begin reversing Australians’ poor mental health outcomes.

*Name changed to protect privacy.

Professor Jane Gunn AO is a distinguished academic general practitioner and inaugural Chair of Primary Care Research at the University of Melbourne where she is also Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Great segment Jane. Totally agree.