GPs and other health practitioners should cultivate “curious openness” to help their lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, asexual or gender and sexually diverse (LGBTQA+) patients who may be survivors of conversion practices, according to experts.

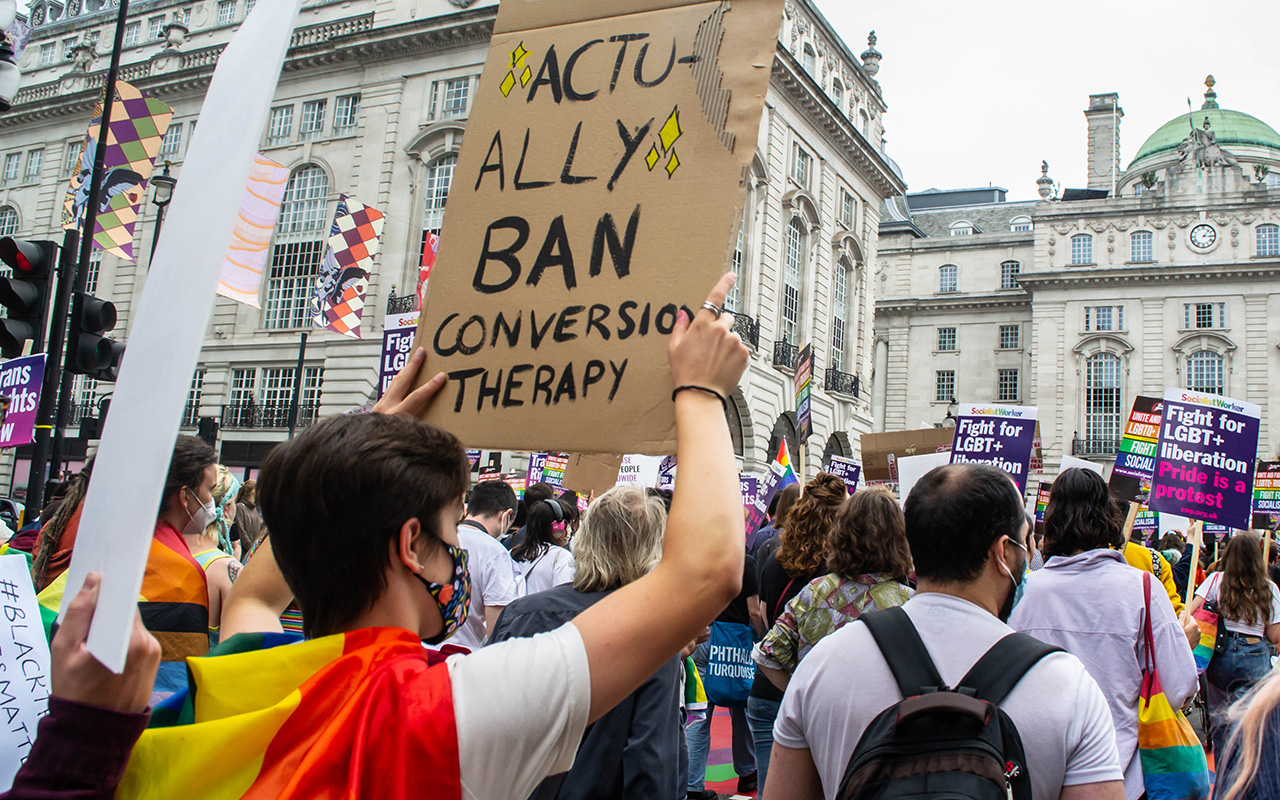

Conversion practices, sometimes known as “conversion therapy”, are any attempt to change or suppress someone’s sexuality or gender identity, according to the authors of a Perspective published by the MJA.

“This can include a whole range of practices – a therapeutic group similar to Alcoholics Anonymous, it might be prayer groups, or it might be more informal practices – but they reiterate the message that a person is broken or damaged because of their sexual identity or their gender identity, and that they can be ‘fixed’ through religious processes or prayer processes,” co-author Associate Professor Jennifer Power, Principal Research Fellow at La Trobe University’s Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, told InSight+ in an exclusive podcast.

There is no evidence of benefit from conversion practices, but the evidence of harms is plentiful.

“International studies over the past 20 years have shown a wide variety of mental health problems associated with conversion practices, including very, very high rates of suicidality,” Associate Professor Timothy Jones, another co-author, told InSight+.

“Our research with survivors and with treating mental health practitioners showed that conversion practices are associated with chronic complex [post-traumatic stress disorder]-type symptoms,” he said.

“Conversion practices introduce a fundamental conflict between a person’s belonging with their religious or cultural community and their gender or central sexual sense of self.

“For many people, this deep conflict between core parts of themselves is completely disabling and leads to harm to the development of their self-concept, their participation in life.

“Lots of our participants said they felt like they couldn’t start their life until they had ‘fixed’ themselves. So they delay education and employment, engagement with civil society.

“We’ve been looking at the spiritual harms associated with conversion practices. People report damage to their ability to find existential meaning in the world, damage to their relationship with their spiritual community, their cultural community, and damage to their relationship with God, or their understanding of the spiritual world.”

So how can GPs and other health practitioners help conversion practice survivors?

“In the interviews that we did with people with lived experience of conversion practices, they frequently told us that it was difficult to find supportive health care,” said Associate Professor Jones.

“Very often, they’d speak to a GP, or go to a mental health practitioner, that had a very simple understanding of what was required to resolve it – come out as queer, and leave your religion behind – simple.

“Tragically, that message reinforces the message of conversion practices: that being queer and having faith or belonging to a minority culture community are incompatible.

“So, there’s a great need for health practitioners in Australia to get better at supporting sexually diverse people, gender diverse people and people from minority religious and cultural traditions.”

“Curious openness” was the key, he said.

“There’s a real problem with silence around this.

“Most people who have experience with conversion practices carry a lot of shame about those practices, and so they will present seeking help for the symptoms of the practices, but may not mention the source of the things they are experiencing.

“Most medical practitioners in Australia are not confident to raise questions about religion, when clients present with issues.

“The most important thing is for GPs and other practitioners is to hold a curious openness about the way that religion might be involved in the problems that their patients are presenting with, and to create a safe space for the patients so they can raise questions and seek help for resolving conflict that they may have between sexuality, gender identity, and religious or cultural belonging.

“That might be a direct question, or it might just be a gentle, curious inquiry about whether religion has an impact on the situation.”

Associate Professor Power said sometimes patients may not realise they have been through a conversion practice, and may not have the words to describe it.

“Patients themselves might not have the language to articulate their experiences, in terms of conversion practices,” she said.

“People might come in showing the symptoms or the damage done by what they’ve experienced, but not necessarily be connecting the dots themselves. Even being directly asked might not necessarily bring someone to be able to say, ‘that happened to me’.

“It’s about awareness and gently asking whether this might be something that’s going on without necessarily assuming or having all the language to speak to it.”

Australian states and territories have recently moved to ban conversion practices (here, here and here), but care of patients involves more than that, said Associate Professor Power.

“The push for law reform has been significant and important,” she said.

“But the civil supports that surround any law reform are really important, because if laws change and the issue is suddenly on the public agenda, and more and more people are recognising it, or starting to have a different understanding of it, or are being more willing to talk about their experiences of conversion practices, there’s got to be some way for people to seek help.

“So investment in training so that health practitioners are prepared and able and confident to ask questions about religion, to ask questions about sexuality, to support people, to make the right referrals is really important.

“It’s fundamental.”

Also online first at mja.com.au

Research: Changes in five‐year survival for people with acute leukaemia in South Australia, 1980–2016

Beckmann et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51423 … FREE ACCESS permanently

Research letter: Sentinel lymph node biopsy rates in Victoria, 2018 and 2019

Watts et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51424 … FREE ACCESS permanently

more_vert

more_vert