IT seems incredible that aged care is once again in the news for all the wrong reasons. After all, it is less than a year since the Australian Government responded to the 2-year Aged Care Royal Commission and heralded its May 2021 budget package as a “once in a generation reform” to transform aged care.

This budget package comprised increased funding of $17.7 billion over 5 years, including $7.8 billion for “funding sustainability” and $942 million to improve quality and safety. From the government’s perspective, aged care was fixed and off the political agenda.

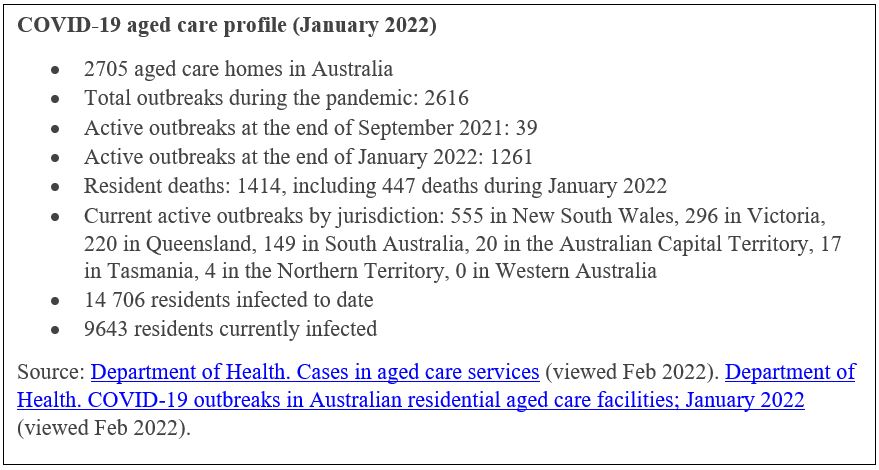

Yet less than a year later, aged care is back in crisis and there are COVID-19 outbreaks in close to half of all aged care homes in Australia. This is despite overwhelming evidence that people in aged care are among our most vulnerable citizens. Of all the sectors that should have been prepared for the end of lockdown, it was aged care. But it was not.

The lead-up: Newmarch, Victoria and the Royal Commission

There are 2705 aged care homes in Australia and they are the responsibility of the Australian Government. State and territories share some responsibilities but only to the extent that states and territories are responsible for public health protection on the ground.

The first major COVID-19 outbreaks occurred in aged care in 2020 in New South Wales, most notably at Newmarch House in Sydney, from April to June 2020, when 37 residents tested positive and 19 died. These were soon followed by major outbreaks in aged care homes in Victoria. By the end of 2020, 2238 residents had been infected and 678 residents had died. Most of these were in Victoria. The case fatality rate was 30% (authors’ calculation).

While there were differences in the details from one outbreak to another, two overwhelming conclusions can be drawn from the experiences leading up to the current Omicron outbreak. The first is that, even after allowing for differences in size and location, better staffed public sector homes did demonstrably better. Residents in private-for-profit homes, with fewer and less qualified staff, fared much worse.

The second conclusion is that most of the responsibility rests with the Commonwealth. It had not adequately prepared itself and it had not adequately prepared the aged care sector. Planning had been deficient, and once outbreaks occurred, they had been inadequately managed. The then Aged Care Royal Commission was scathing in a special report on aged care and COVID-19 that it published in October 2020.

The bigger picture is that systemic problems that had existed in aged care for more than a decade – funding, workforce and governance – had resulted in the aged care sector being in crisis even before the pandemic began. The pandemic found a ripe environment for the tragedy that subsequently unfolded.

Vaccination rollout in 2021

January 2021 saw the government announce a COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy. Aged care residents and staff were identified as first priority populations and included in Stage 1a. The goal was that all of phase 1a would be vaccinated by the end of April 2021, with boosters available 12 weeks later. If this had happened, second doses would have occurred by the end of July 2021.

But, like the rest of the vaccination program, the aged care vaccination program was eventually implemented several months behind schedule. This then delayed the third dose booster program, which did not begin until 8 November 2021. On 24 December 2021, the government reduced the interval between doses to 4 months. But by then the Omicron outbreak had already taken hold.

2021 and Omicron

The current Omicron variant emerged in November 2021 and it has spread like wildfire both in the general community and into aged care (see box).

The current toll now equates to a 9.62% case fatality rate. The case fatality rate for the general community stands at 0.15%. Aged care residents represent 0.74% of the Australian population and 0.59% of COVID-19 cases. Yet they represent 36.87% of all COVID-19 deaths in the pandemic so far (authors’ calculations).

What has gone wrong this time?

In addition to ongoing systemic failures in aged care, four specific issues have exacerbated the breadth and depth of the current outbreaks in aged care.

1. Government decisions to end lockdowns and ease restrictions based on general population vaccination rates rather than whether the aged care sector was prepared

NSW was the first jurisdiction to announce a revised roadmap out of lockdowns and restrictions in the lead-up to Christmas 2021. This was soon followed by similar announcements in other jurisdictions as well as the opening up of domestic and international borders.

The timing of these various roadmaps was driven by the percentage of the eligible population who were vaccinated. This failed to take into account whether systems and resources were in place to deal with the inevitable surge in cases in the aged care sector. A similar observation could be made about the health and the disability care sectors.

In the case of aged care, the sector was not ready when states and territories opened their borders and eased restrictions. This no doubt reflects the lack of coordination between the Commonwealth, responsible for aged care, and states and territories, responsible for managing the pandemic on the ground.

2. The vaccination program in aged care

While the vaccination booster program is apparently ahead of schedule, it has come too late to aged care homes caring for residents in the current outbreak. Residents needed to have their booster vaccinations before, not after, lockdowns and restrictions were lifted. Some homes are still waiting.

The other major problem is the design of the booster program itself. Each home is visited only once. Residents who are not eligible on the day, are unwell or are not in the home on that day simply miss out. Homes are then responsible for organising vaccination on a case-by-case basis. They are looking to GPs and state vaccination hubs for help with this.

A one-off vaccination program is not good enough in a sector that has considerable resident turnover. The aged care sector has around 180 000 beds and around 240 000 people moving through those beds in any one year. With a one in three bed turnover, aged care needs a regular program of visits, not a one-off event.

3. Access to rapid antigen tests (RATs)

One of the real tragedies of the pandemic to date has been the social isolation of aged care residents. The first response to an outbreak has been to lock families out and lock residents in. This is despite the fact that there is no evidence that visitors are a major source of COVID-19 infection.

Easy access to RATs is a critical part of protecting residents as well as staff and is key to opening homes up to visitors. But access to RATs is still hit and miss.

There is no concept of prevention. Homes are only provided with RATs after they have an outbreak, not before. And, even then, the supply homes have been receiving has been inadequate.

It took until late January 2022 for the Commonwealth to agree to provide RATs for residents, but still only in homes that already have an outbreak. Until then, the Commonwealth had been arguing that testing residents is a public health function and is thus a state and territory responsibility.

4. Access to adequate and affordable personal protective equipment

Aged care homes are receiving some equipment supplies from the national stockpile but are required to purchase other items themselves. The financial costs to homes can be considerable, exacerbating existing financial pressures in the sector. This is not financially sustainable in the longer term.

Bigger issues

The early waves of the pandemic saw considerable debate regarding responsibility for COVID-19 management in aged care as well as blame-shifting between government and providers. The Commonwealth perspective was that responsibility lies with aged care providers. However, the capacity of providers to respond is fundamentally dependent on the policy parameters and resourcing that the government provides.

As the Royal Commission revealed, there has been a long-held agenda within the centre of government to curtail projected costs associated with an ageing population, in particular aged care. This has been addressed explicitly by introducing higher fees and charges for services and routinely failing to increase funding to the sector along with consumer price index, as well as implicitly through expanding the number of private-for-profit providers in the sector under the ideological and rather naïve assumption that this would increase competition and drive efficiencies.

This has resulted in a significant shift in the staffing profile of those providing care to our most vulnerable citizens, with experienced clinicians such as registered nurses being replaced by less costly and less skilled personal care workers. The outcome is that over half of all aged care homes have unacceptable staffing levels compared with international benchmarks.

Attraction and retention of aged care workers is fundamental to addressing the quality and safety of aged care. One key element of this is remuneration. Aged care workers are very badly paid and there are cases going to the Fair Work Commission this year seeking a pay increase in the order of 25% or $5 per hour. The Commonwealth has declined to be a party to the case and has so far not committed to fund any pay increases. Yet this is fundamental to stabilising the sector and making it safe.

This mindset of the Commonwealth in having a hands-off approach to aged care also explains the lag in response times at each step of the pandemic: from getting access to personal protective equipment, addressing workforce challenges, providing advice regarding visitors, rolling out the vaccinations and, most recently, providing access to RATs for staff, residents and visitors. It is not as if the Department of Health is unaware of the challenges currently being experienced by the sector; it is simply that it does not consider that it needs to take a leadership role in responding.

This is not surprising, as the current crisis yet again reflects the reactive and iterative policy making that has characterised aged care in recent decades. And while responsibility for aged care remains centrally controlled at the national level, this is unlikely to change. The Australian Public Service does not have established implementation expertise, and its policy expertise has been deliberately hollowed out by recent governments that have increasingly relied on politicians’ staffers and external contractors for policy advice, which invariably focuses on meeting the political objectives of government rather than the broader needs of the public.

This has severely constrained the ability of the Commonwealth to understand, let alone deal with, the complexities such as those experienced by the aged care sector today. Addressing the challenges experienced within aged care as a result of COVID-19 requires sophisticated and systems thinking and additional funding.

At the operational level, it is clear that a centralised bureaucracy in Canberra is not capable of fixing aged care’s deep and systemic problems. Real reform will only be possible if the management of the whole national aged care system is decentralised to the regional level. The question is, will any future federal government be prepared to do this?

Professor Kathy Eagar is Director of the Australian Health Services Research Institute at the University of Wollongong. She has over 35 years of experience in the health and community care systems, during which she has divided her time between being a clinician, a senior manager and a health academic.

Anita Westera is a Research Fellow at the Australian Health Services Research Institute at the University of Wollongong. She has a strong interest in driving evidence-based policy and program development to improve the lives of vulnerable people and communities.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

What’s the difference between operating a RACF and operating a squadron of jets, or a frigate, or an SAS battalion – HEAPS

What’s the difference between operating a RACF and operating a school, hospital, prison, social housing – NOT A LOT

The federal government, irrespective of which party is in power, should not have any operational involvement in the provision of ‘domestic’ services. It should fund and regulate (via inter-government agencies) but operations should be devolved to the states and dare I say local/regional governments.

Agree with 2:17pm above .

Vaccine stroll out was /is a problem . We were ready to open at weekends from beginning March 2021 in Rural NSW but have only done so on 3 Saturdays as supply did not warrant this.

Lack of RATS is problematic . We cannot get any with base patient load of over 10,000 whereas State jurisdictions can for those who can access them through NSW Dept Education Health and Justice health.

Back to NHomes find their different clunky computer systems and red tape stymies good care . Often impossible find past history pathology etc. Rely on practice computer system to keep abreast of matters and is much more friendly than State system of EMR .

So proper staffing ratios, probably mandatory , better pay which equals high taxes ,

? increased Medicare levy ,but then no pay tax no get service . Such is life which politicians seem to avoid like the plague.

Not sure I see the logic in devolving to regions. There would still need to be central policy making, funding and oversight.

Isn’t part of the problem that ratios are not mandated, and in my opinion it should never be run for profit as this creates an automatic conflict of interest.

My major concern in the recent aged care figures of ” booster”/ 3rd dose vaccination is the large number of aged care residents who did not receive the dose. I would have hoped that those aged care facilities involved had arranged en masse vaccination when they fell due.

As usual Commonwealth Govt is doing too little too late. The PM and Aged Care minister seem to be on another planet when it comes to aged care ie totally dissociated from the reality of the situation and again minimal reactive policy making on the run, rather than paying any useful attention to the recent Aged Care report and

its recommendations.

The Government must provide more funding to stop the decline in aged care services instead of wasting huge amounts of money on the climate change scam, global warming scam, CO2 emission scam, and Great Barrier Reef scam. None of these things are happening, and they are not urgent if they were. However aged care services are declining at an appalling rate. Aged care needs urgent attention and increased funding. So stop wasting money on things that don’t matter. Spend it on improving aged care services.

As a GP visiting aged care facilities regularly I agree and despair equally with the author’s of the article. The federal government has to do better and fast in terms of supporting the aged care industry. It’s a joke to attend only once to offer immunisations, to skip people who can’t or haven’t had their relatives return a consent form, to miss the new residents etc. Overall, it is harder than ever to provide good care to residents with the system falling apart, COVID ripping through and don’t forget the unbelievable red tape (all those forms etc).