WHILE ordering your “tea, Earl Grey, hot” from a Star Trek-style replicator may be some years off, the technology to 3D-print personalised medications tailored to a particular patient’s needs is well and truly here, even if the regulatory framework needed is lagging behind.

Imagine a world where you have a patient coming off antidepressants. Instead of cutting tablets to get half and quarter pills to step down the dose, imagine ordering customised pills from the pharmacy at exact doses 3% less each day until withdrawal is completed.

That’s one of several scenarios envisaged by University of Queensland researchers Amirali Popat and Liam Krueger, who have written a Perspective on the subject for the MJA.

“This is where the future is heading,” said Associate Professor Popat in an exclusive MJA podcast.

“I know it sounds like a sci-fi movie – you press a button and the drug will be printed – but it will happen, and it will happen very shortly [technologically].”

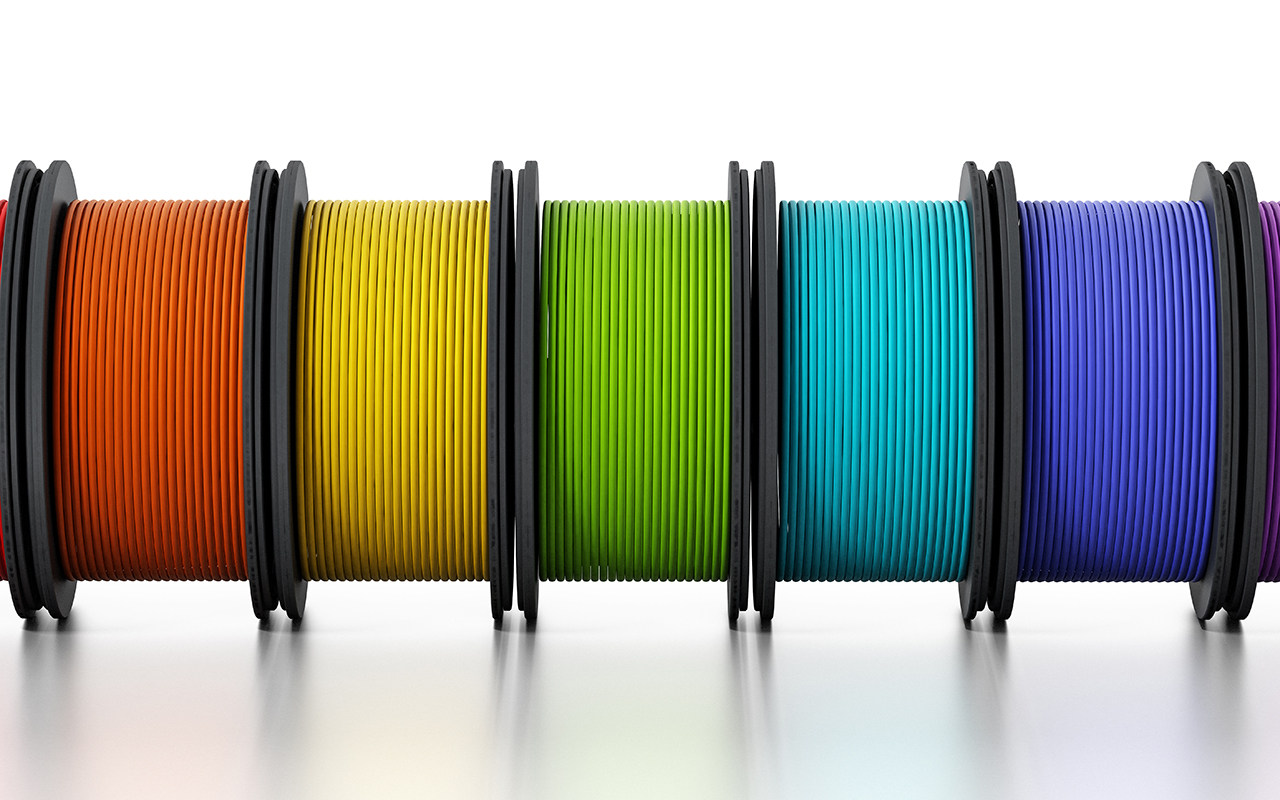

The technology – the printers themselves, the polymers, the filaments – already exists, and clinical trials have already shown personalised medication production is doable. What is missing in Australia is the legislation and regulatory framework.

“There is one 3D-printed pharmaceutical currently on the market in the US which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration,” said Mr Krueger, a pharmacist and PhD candidate at the University of Queensland. “There’s no legislation around it in Australia. There are no regulations around 3D-printed dosage forms, and definitely nothing in the way of customising doses.”

Even the American product – levetiracetam, an anti-epileptic in the form of a tablet that dissolves on the tongue – cannot yet be personalised by dose, coming only in fixed strengths.

Missing from the equation is the large amount of data from clinical trials needed to convince regulators.

“We still don’t have the amount of data behind it to get regulatory approval,” said Mr Krueger. “For that, we need very large-scale clinical trials, that can take a lot of time and money.”

And that’s where Big Pharma could come in, Popat and Krueger say.

“One of the interesting things that could come out of this is that a lot of drugs don’t make it to the public because of lack of demand, a small market, or because the pharmaceutical company saw no real benefit to manufacturing them in the larger scale,” said Associate Professor Popat.

“[With 3D printing] a lot of those drugs can come back on the market, because you could actually make very small batches of them.

“You don’t necessarily need to make them in hundreds of thousands. You could make smaller dose forms; you could do lots of smaller clinical trials with those drugs much more easily. It’s more feasible and it’s more cost effective.

“Where [Big Pharma] would save on costs is in logistics. Ideally, you would have printers set up at compounding pharmacies and hospitals throughout the country.

“All you’ve got to ship is the filaments that are feeding the drug-loaded polymer through the nozzle to build the tablet. All the tablets are printed on site for the patient. You’re not having to ship thousands of boxes to the pharmacies every day.”

Krueger and Popat detailed other advantages 3D-printed medications could provide.

“Perhaps the most exciting opportunity is the potential to reduce the tablet burden of our ageing population, with an example being the five-in-one polypill,” they wrote in their MJA article.

“In practice, a combination of several drugs is often used to achieve optimal patient outcomes for many conditions, such as in heart failure and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In these complicated treatments, an advanced 3D-printed medication regime could simultaneously help the patient take the right medicines at the right doses at the right time, while also reducing the number of pills the patient must swallow.”

Disaster relief and times of shortage could also prove a forum for 3D-printed medications.

“The ability to 3D-print tablets with fewer components also potentially provides a solution for medicine supply shortages in times of disaster,” Popat and Krueger wrote.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients have been unable to obtain adequate supply of several commonly used medicines. In Australia, this may be worsened by long supply chains, where medications are made and processed overseas before being freighted to Australia.

“A compounding pharmacy or hospital with access to extruders, 3D printers and bulk quantities of raw medicine and polymer base could manufacture replacements on site to ensure adequate supply of regular medications during unexpected shortages.”

And that bacon sandwich manufactured in a slot in the wall may not be that far away, either.

“There are a lot of food companies who are currently making snacks fortified with vitamins and minerals,” Associate Professor Popat told InSight+.

“A lot of those are extruded products. The technology behind that is not very different from what we are talking about with 3D-printed medications. The first step of extrusion is very similar in that raw materials go through that process of melting and resolidifying.

“What we’re doing is we’re using medicine or drugs with a polymer that can form a tablet instead of making a snack.”

In the conclusion to their MJA article, Popat and Krueger cautioned that there are hurdles to overcome before 3D-printed personalised medications are commonplace.

“Although the patient and practitioner benefits are apparent, without regulatory approval or further interest of pharmaceutical companies in 3D printing, seeing the technology in practice may not be a reality over the next 5–10 years,” they wrote.

“Hopefully, personalised medicine will become available, all in a dosage form 3D-printed at a local hospital or pharmacy at the click of a button.”

Online first at the MJA

Medical education: COVID-19 mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty)-induced myocarditis

Wong et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51394 … FREE ACCESS permanently

Perspective: A large trial of screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States highlights the need to revisit the Australian diagnostic criteria

Doust et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51388 … FREE ACCESS for 1 week

Research: The prevalence of tinnitus in the Australian working population

Lewkowski et al: doi: 10.5694/mja2.51354 … FREE ACCESS permanently

more_vert

more_vert

I have never liked the “one size fits all” approach. We come in differing sizes, commonly ranging from 40 to 120 kg and uncommonly in a greater range, as well as a wide range of compositions, especially of lipid, protein etc. If technology enables practicable personalisation that will certainly be an advance.